Now, the tech company has collaborated with artist Simon Denny on his new many-layered exhibition, Mine.

Mine is Mona’s most technologically ambitious exhibition yet. It combines installation and sculpture with augmented reality, as well as visitor interaction and real-time data extraction on The O. It runs until April 13, 2020.

Blooloop talked with Nic Whyte, co-founder of Art Processors and Simon Denny about Mine, the technology, and the unique collaboration between artist, curatorial staff and tech company.

Simon Denny: Mine

Mine is a “theme park to extraction” of both the mineral and data kind. It’s enormous in its intellectual scope. New Zealand-born Simon Denny explores notions around some of the world’s more complex and interconnected systems. For example, capitalism, labour exploitation, technological development, and environmental catastrophe.

Visitors can play “Extractor,” a data-themed version of a classic Australian sheep farming board game Squatter. “Extractor” can also be purchased by visitors to take home and play. A giant display version of this game sits on a room-sized version of Squatter, alongside giant replicas of machines and products used in automated mineral mining.

Inside a human worker cage—originally patented by Amazon.com—flits a virtual King Island brown thornbill, a rare bird on the brink of extinction, brought to life in AR.

Over two-and-a-half years, Art Processors and Denny collaborated with exhibition curators Jarrod Rawlins and Emma Pike on exhibition design, creative conceptualisation, and technology integration for the Mona-commissioned project.

Bringing its expertise in extended reality and data analytics, Art Processors developed custom AR and facial recognition technology for The O, along with 3D design and audio production. The company also helped Denny “mine” Mona’s real-time visitor data, finding new ways to show visitors the kinds of data museums can collect about them—adding another layer of reflexivity to the provocative exhibition.

Art Processors, Mona and The O

Art Processors enjoys a long association with Mona, having originally invented The O in time for the museum’s opening in 2011. It’s what led to the tech company’s formation that same year.

The O replaces traditional wall labels and texts in the cavernous, maze-like museum, using indoor location technology that finds visitors wherever they are and tells them about the artwork on display closest to them.

Visitors use The O to read and listen to “Artwank,” Walsh’s ramblings about his private collection, interviews with artists, and family-friendly content. They can “love” and “hate” the art, join virtual queues for special exhibits, and save their visit for viewing off-site.

Whyte says The O put Mona at the cutting edge of museum mobile technology when it launched and continues to push the boundaries of museum mobile experiences.

During the initial development of The O a decade ago, Art Processors’ founders worked closely with Walsh and his team of exhibition designers, art directors, architects, and curators to design the application.

“It has enabled Mona to declutter, essentially. Painting the walls black and reducing the illumination to the point where it is just beautifully lighting the objects and artworks,” Whyte says. Today, the company continues to experiment and innovate with The O, introducing new functionality as requested by museum staff and inventing new features that Mona’s owner, David Walsh, dreams up.

For Mine, augmented reality and emotion detection were two of the new technologies Art Processors developed for The O.

Simon Denny and Mona

Denny is a contemporary artist based in Berlin who has been a professor for time-based media at the HFBK Hamburg since 2018. His work unpacks the social and political implications of technology and the rise of social media, startup culture, blockchain and cryptocurrency.

He has held exhibitions around the world, including major shows at MoMA PS1 in New York, the Serpentine Gallery in London, and Christchurch Art Gallery in New Zealand. He represented New Zealand at the 2015 Venice Biennale, where he also met Walsh.

“We had a long conversation about what might be possible at Mona, says Denny. “I visited the museum several times, and I knew about the museum, of course. But had not actually been there before 2016. I looked at the space and talked with the curatorial team. [Mine co-curator] Jarrod Rawlins in particular, whom I knew from other projects we’d worked on together before he joined the museum.”

It was challenging, he explains, to settle on the right piece of work to create for Mona. Ultimately, he considered the physicality of the space, as well as Australia’s history and economy.

“It is this amazing hole in the ground, raw, shaft-like. When I went in there, I was immediately struck by possible associations: something underground, a mine,” he says.

“I felt it was important to include these different reactions in the story.”

Art, technology and extraction

Denny’s work has often explored the politics of technology companies and the way they communicate themselves to the world.

“I was trying to follow conversations from the technology industry about automation and labour, and worries about robots taking jobs,” he says. “All these connotations came up, and I decided to do something that looked into this, but also made sense in this space.”

A long period of research followed. The result was Mine, an exhibition that contains work by a number of artists as well as Denny. It has a multitude of intricate and complex layers—both thematically and digitally—including an augmented reality layer that Denny co-produced with Art Processors. The underlying theme explores a broad narrative around extraction.

“Extraction is the keyword,” says Denny. “There is mineral extraction from the ground, mining. But there is also extraction as it works in data, and platform capitalist models of business.

“I was trying to draw a line between those forms of extraction while tying it to Tasmania and the context of Australia.”

The O

The O is core to the Mona experience. Over 94 per cent of visitors to the museum use it to engage with the museum’s collection. Whyte says the curators and Denny came up with the idea of leveraging The O for Mine since it was already ubiquitous inside the museum.

“Initially, it came about in a conversation we had with Simon in December 2017. Simon imagined that The O could provide some sort of sub-narrative to the entire exhibition,” Whyte says.

“As the idea evolved, and as we started looking at ways in which this could exist, it became a central part of the exhibition. Not so much a sub-narrative, but the narrative. It became integral to the overall understanding of the exhibition.”

Mine, The O and augmented reality

The O also provided a ready platform for implementing augmented reality.

“Simon’s exhibition Mine at Mona is around humans and machines coexisting. The idea of mining in the traditional sense, but also data mining. It looks at mining in terms of the rare minerals and materials that go into technology: the life cycle of technology,” Whyte says.

“Wrapping all that up, The O is a device inside of Mona that captures a vast amount of data around what visitors are loving and hating. It shows their movement through the museum, how they interact with the virtual queues, and how visitors are engaging with the collection.

“Simon was really interested in bubbling that content back up and re-interpreting it within Mine. Additionally, he was interested in AR markers. This is a version of a QR code. One that can recognize and overlay 3D content in the physicality of the sculptures that he was putting into the space.”

Humans and robots

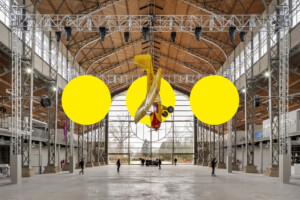

The exhibition covers three galleries, each with their own parallel experience. Perhaps the most visually powerful of these is the first: a dimly lit space where visitors find a metal cage modelled on a patent drawing by Amazon Technologies.

This was designed in 2016 as a cage to enable human workers to negotiate robotically organised “human exclusion zone” sorting systems. However, the cage was never actually built by the ethically controversial company.

In Mine, Simon Denny has given it physical form.

“It was highlighted in a research paper on Amazon Echo by some friends of mine from the AI Now Institute at NYU [a research institute studying the social implications of artificial intelligence],” Denny says. “It was such an interesting meeting point of humans, labour and algorithms. I liked the idea of putting the cage in this mine-like space.”

The caged bird sings

Reminded of the notion of the canary in the coalmine—a bird that in years gone by served as an unpaid worker, signalling environmental toxicity by its death—Denny considered the concept of a bird in the cage, evoking that history.

“I researched and came across scientists at the Australian National University. They were trying to raise the awareness of birds that were about to become extinct,” he says.

One such bird is the King Island Brown Thornbill. This has the unfortunate distinction of being the Australian bird most likely to become extinct within the next 20 years.

“There are now very few of these animals. We got in touch with the ANU researchers. And they told us: ‘We don’t even know if there are any left. We’re about to send a research team in to try and document this bird, to raise the profile.’

“Mona was able to contribute some funds towards that expedition. And they came back with this incredible recording, the first-ever audio recording of this bird. It was amazing.”

A unique experience at Mine

Denny was then able to work with Art Processors to build a 3D avatar version of the bird. This virtual bird “lives” inside the Amazon worker cage.

“Focusing on the work I did with Nic and his team, it was an amazingly simple and very beautifully executed experience. Mona is a very special museum in that everybody already has The O in their hand,” he says.

“If you’re designing augmented reality experiences, that is very useful. People don’t have to adjust to a device specifically for one exhibition experience. They’re already interacting with it.”

A decision to dispense with headphones means audio of the rare species’ bird call emanates from The O into the gallery space.

“When you get several people around the cage at the same time, you have this uncanny experience. You can hear a lot of the birds tweeting away, but there is no bird. You are looking through this device, which activates this nearly-extinct bird and you hear a flock of them. Possibly more than there are out there in the real world,” he says.

“There is this empty cage standing there. So, the only way you can see the bird fluttering about is through the device in augmented reality.”

Mineral extraction

The technology responsible for the data collection may raise the profile and possibly save the endangered bird. However, in a paradoxical twist, it relies on mineral extraction that depletes the environment and destroys habitats.

“The technology that you use to experience the bird and the cage is thanks to extractive mining practices. I think that is also a bind that we find ourselves in, too,” Denny says.

“The reason humans know that climate change even exists is because of measuring devices and strategies and systems of classification. But these are, in themselves, potentially making the situation worse.”

Mining processes

The exhibition’s second room is a multicoloured, visually busy experience. It comprises a cardboard version of machines used for mining and a trade fair set atop a life-size board game. Modelled on Squatter, an Australian game invented in the 1960s, Denny’s version of the game, Extractor, is based not on sheep farming but on the dynamics of platform capitalism.

“Instead of being a farmer, you’re building a Google or Facebook, one of these large global platforms,” Denny says. “Instead of keeping sheep on your land, you keep data in the “cloud” (storage facilities). You monetize not on the wool, but on the data you collect,” he explains.

“There is also another augmented reality layer on top of that. This plays advertisements for the automated mining machines, which are modelled in the space, and tracking the viewer’s experience.”

Mineral mining machines, Denny explains, are becoming increasingly automated. There are fully automated mines being proposed and built that need no people on site.

“Some of the most high-profile mines are heading towards this people-less mining scenario,” he says. “And the machines modelled in the exhibition are based on machines used in Australia for building automated mining rigs.”

Work and technology

Simon Denny gave the third room over to the curatorial staff, Mona’s Jarrod Rawlins and Emma Pike. Their role here was to curate a group show based on figurative sculptures.

“I gave them the open brief that they could do anything they liked, and put any number of artworks in there. As long as they were all human figures having some sort of reflection on work and technology,” he says.

“Then we designed a raised scaffold for them to stand on. Underneath are markers for an augmented reality experience I designed with Art Processors. Scanning these markers shows all the data that your device is capturing as you go through the museum.”

A mine of information

To deliver location-aware experiences throughout the museum site, The O tracks every visitor’s movements and interactions. It then feeds this data back to Mona. Mine taps into this real-time data, collecting information about how visitors interact with the exhibition and the museum as a whole.

This information includes how long visitors stand in front of a particular work. It also logs which artworks they’ve seen and in what order. In addition, it details their time spent in augmented reality, and what they’ve “loved” and “hated”. This is as well as museum-wide statistics, such as how many people are presently on-site.

“Mona is an interactive space, but it’s also a data capturing space,” Denny says. “In the context of my show, I was doing so much about how data is used, how extraction is structured, and where the slippage between mineral and labour and database business systems exist that I thought it was important to make what was going on in the museum transparent to viewers too.”

“So you scan markers underneath the platforms and information appears on your screen. All this data is coming through the devices, which enable your experience in the museum.”

Simon Denny on working collaboratively

Simon Denny describes the experience of creating Mine as a collaborative process. One involving many different layers of the museum: Art Processors, curatorial staff and a production team. As well as in-depth conversations with Walsh throughout the development of the exhibition. He also worked with his own studio team and advisors around the world.

He says it’s a process he has become accustomed to.

“I like to have other people’s input when I’m developing a project. Because people have different levels of expertise in different spaces. I have a limited capacity, in many things, so I rely on others.”

He says, similarly, the filmmaking world and teams putting together larger exhibitions work collaboratively as a matter of course.

“When the budget is there and the willingness is there, I like to get as many experts in on a project as I can,” he says. “Nic and Art Processors were a big part of that: very capable and an easy partner to work with. They were open to working with their data, making their processes transparent, and working with narratives that had an edge to them.

“I thought that was really cool. It was a very positive experience.”

Images kind courtesy of Mona/Jesse Hunniford.