The Barbican Centre is an internationally renowned arts venue in central London. A masterpiece of Brutalist architecture, the centre is known for experiences that are as unique as its location. Its experiential department, Barbican Immersive, opened its latest touring exhibition, Feel the Sound: An exhibition experience on a different frequency, on 22 May.

Barbican Immersive uses technology and digital creativity to explore big ideas in new, inspiring and unexpected ways. Its new exhibition will show at the Barbican in London throughout the summer, before embarking on an international tour.

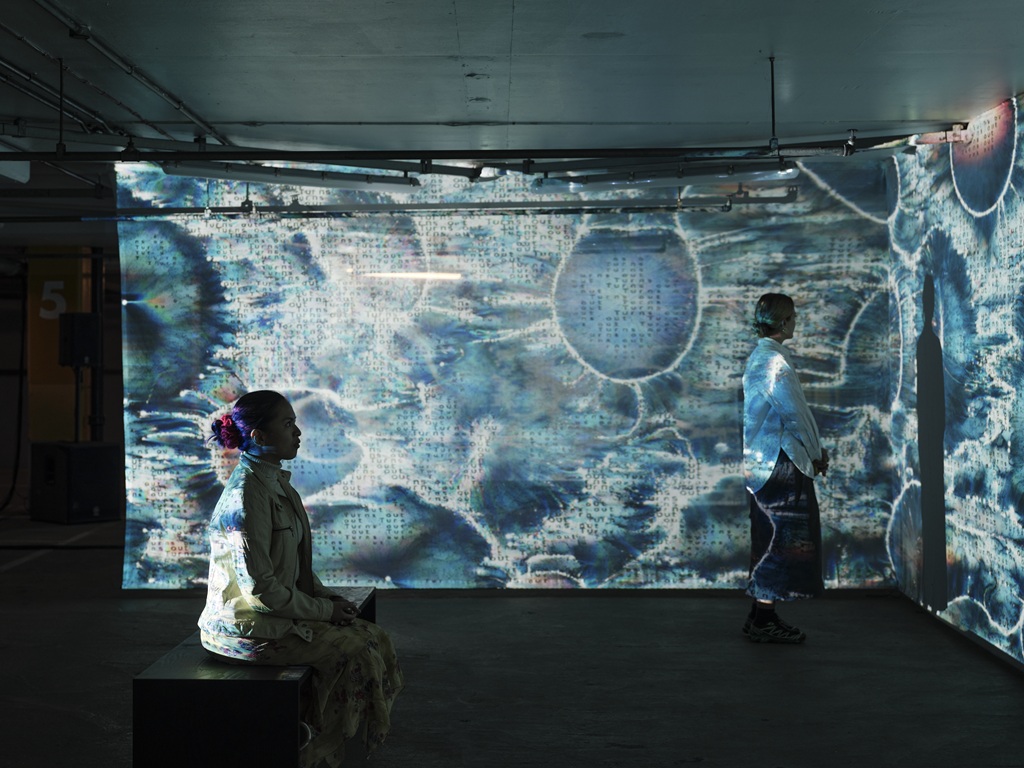

In an experience weaving throughout the Centre, visitors will discover how sounds shape emotions, memories, and even physical sensations, as they explore what it means to listen with their entire body.

We spoke to Luke Kemp, head of creative programming at Barbican Immersive, about the exhibition, audio design, and the immersive experience.

‘We’re all sonic beings’

“Feel the Sound is not just about the feeling that music gives you, or sound gives you, but this idea of the texture, the shape and the physicality that it is more than an audio experience,” says Kemp.

“In the world as it is today, there are a lot of distractions and a lot going on. The world could feel like a noisy place that’s constantly fighting for our attention.

“How can we get people to tune in with themselves and think about what listening might actually mean?

“Principally, we’re trying to explore with people that we’re all sonic beings.

“We’re made up of vibrations and frequencies, as the world is. If you’re able to tune into your body and use your whole body as a listening device, whether you listen with your ears or your eyes or your hands or any other part of your body, you can transform what listening is.

“And maybe you can transform how you see the world completely.

“That’s a big claim, but that’s the idea. And it’s taking something that might feel quite familiar, and just turning it a bit to give a different view and perspective.”

Feel the Sound promises to transform how we think about sound. Visitors will encounter 11 interactive installations, including a car-park dance party, participatory digital choir, and music without sound. Additionally, the installations are accompanied by two experiential ‘playgrounds’ which invite visitors to explore the exhibition concepts.

Feel the Sound: collaborative audio exploration

Feel the Sound is part of the Barbican-wide summer 2025 season, Frequencies: the sounds that shape us. In this, the exhibition will be accompanied by the award-winning Virtual Reality experience In Pursuit of Repetitive Beats by Darren Emerson, and a programme of creative collaborations and performances.

After its run at the Barbican, the show will embark on an international tour including to MoN Takanawa: The Museum of Narratives, Tokyo, a new museum and cultural institution set to open in Japan in 2026. MoN Takanawa is the co-producer of Feel the Sound, and its director, Maholo Uchida, is a long-time Barbican Immersive collaborator.

This partnership has led to the Barbian working with artists such as Miyu Hosoi, Daito Manabe and the Ryuichi Sakamoto estate, among others.

“As part of the research phase, we went to Tokyo and met with the team there, and Maholo was able to open up lots of conversations,” says Kemp.

“We hope that we can foster this kind of collaborative relationship with museums, and that we can work with tour venues and then start to build longer-term relationships and collaboration as well.”

Artist focus: Miyu Hosoi

Sound artist Miyu Hosoi spoke to blooloop about the exhibition.

“For me, sound is a trigger for the expansion of perception. So I am always trying to think about the space itself, not only the sound I play.

“I try not to provide too much information to the audience, because I don’t want to steal their room to think about something through my work.

“It’s important to remember that the sound is ambiguous, and that means there is a huge space to think under it.”

Her newly commissioned work, Observatory Station, is on show at the Barbican’s Silk Street entrance.

“I want to make a space to observe the world through sound,” says Hosoi.

The installation centres on a line of 12 speakers which play field recordings. These are gathered from recorders worldwide, the artist’s database, and contributions from the global sound project, Cities and Memory.

“But it’s too simple, just playing field recordings from the speakers. So my engineer, Takayuki Ito, and I are making a playbook system based on the location data and the time code when the sound was recorded.

“People will hear the sound of 8 am in each country, depending on the grid. That means maybe we can hear the bird singing in the morning in each area. Or, let’s say the sound recorded at noon in standard time in London is coming one way, and the 8 pm sound from Tokyo is coming the other.”

Inspiring collaborations

Hosoi’s collaboration with Cities and Memory is integral to the development of the work.

“I asked Cities and Memory to collaborate, and their community provided me with lots of nice field recordings, and thinking about the concept and playbook system.

“I found that, from the Cities and Memory sound and sources on the Internet, there are lots of really beautiful descriptions about the sound sources. There’s lots of sea sound, lots of insect sound, lots of rain sound. I found that using that description, I can build a nice system.

“Because time, location, and words, these three things are made by humans to understand the world.”

Such collaborations, says Hosoi, enrich the work while also championing the community.

“Stuart [Fowkes, sound artist and field recordist] at Cities and Memory and I found that we have the same passion for using field recordings. It was easy to talk and move forward.

“Stuart also found merit in working together. He said he wants to make the community a bit bigger, and it is good timing to work with the Barbican.

“I don’t work only by myself. Because I’m not an engineer. I understand that maybe I can do something by myself, but that limits what I can think about. I don’t want to have any limits to think about ideas.

“And I don’t put any limits on my engineers. It works well for my projects, and they always make a programme beyond my expectations.”

‘The advent of spatial audio’

This sense of community and collaboration is a theme throughout the exhibition and the Barbican’s wider approach.

“A big part of this is working with advisors and thought leaders,” says Kemp.

“There’s no single curator. We are a team that commissions and produces works, and having more people involved in that conversation helps to emphasise the expertise and the possibilities as well. So that conversation is as international and broad as possible.

“The more ideas you can share and generate, the stronger something can be.”

The development of Feel the Sound comes at an exciting moment for audio technology in exhibits.

“The advent of spatial audio is beginning to have an impact on people and people’s experience, because it’s changing what immersive can be,” says Kemp.

Tom Slater from Call & Response Studios, exhibition audio designer, says: “What’s arrived in the last few years is an understanding of what spatial audio is, what’s possible, with artists, curators and producers.

“Galleries are realising that sound can do things images can’t. It can carry emotion, guide movement, and change the atmosphere of a space in a very immediate way.

“Spatial audio systems are becoming more flexible and affordable, and more artists are working directly with these tools.

“If people can’t make with it, or if you’re restricting the amount that gets made, then you know you’re restricting users. And audiences. There’s a kind of tipping point. A critical mass, where enough people are doing it to make enough people understand it.”

Crafting holographic sound

The Barbican’s unusual architecture presented a unique challenge for the exhibition’s sound design.

“The Barbican is a big concrete bunker. So, the sound will bounce all over the place, especially in spaces like the car park and the Curve Gallery. It’s been a real challenge,” says Kemp.

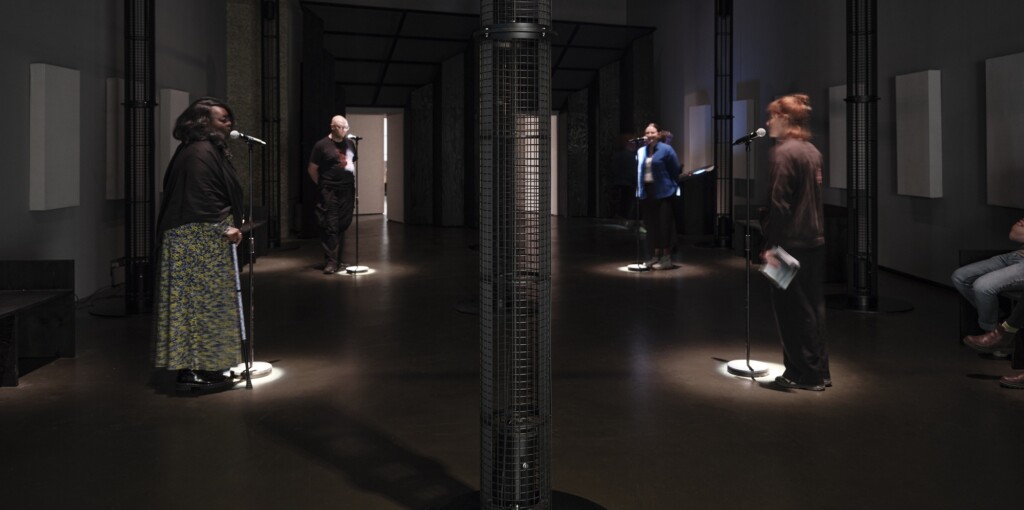

“The best sound experience will be in the Curve itself. We’re working with the TRANS VOICES choir and MONOM, which is a spatial audio studio. So getting that space right is important.”

This piece, UN/BOUND, seeks to encourage deep listening as a driver for change. Visitors will hear voices that blend and harmonise using holographic spatial audio technology as they move through the space.

“If you imagine a stereo, you can create the illusion that the sound’s coming from the middle of the speakers by panning it down the centre, so the sound just comes equally out of both speakers,” says Slater. “But your brain thinks it’s coming from the middle of that position, even though there’s no speaker.

“Times that by 40 something. Then imagine it wraps around. Now, as an artist or a designer, you can have sound positioned in 3d space over time. And it can also move as part of your compositional approach.

“It’s very compelling as an audience. I’ve been working in this field for 20 years, and it’s still highly emotionally compelling and involving to be standing in, and in a sense, suspended by, sound.”

Temporary Pleasure

For Feel the Sound, the Barbican has repurposed its car park as an exhibition space for the first time.

“It is a car park. It’s going to go back to being a car park,” says Kemp. “So, how do we use that?

“There will be car sound systems in that space, as well as another audio experience. And part of it is feeling like you’re still aware that you’re in a car park. But we are shifting that a bit.”

In Joyride by Temporary Pleasure, four wrecked cars provide a portal to Y2K’s DIY music and boy racer communities. The Tokyo Tuner, The Lowrider, The Bimma, and The Boy Racer have been created by contemporary queer and DIY collectives. They offer a combination of sound system, sculpture, and dance floor.

“There are four car sound systems in the doors and walls, and we’ve cut one down the middle so we can tour it. The whole car comes apart and goes back together again,” says Slater.

“The exhibition ranges from very advanced high-tech systems to very low-fi DIY stuff, like homemade calabashes [as part of Resonant Frequencies by Evan Ifekoya] and cut-in-half cars.

“It wasn’t just about saying, let’s get the most advanced system. You want quality and product values and that kind of thing. But also sometimes you need to make something strange and unusual that’s very low-fi and DIY to realise the work.”

Designing the audio experience

So, how do you design an audio experience for such a diverse environment?

“The brief was to create a sound design that could connect eleven very different commissioned works into a coherent experience — something that had emotional flow and a sense of atmosphere, but still allowed each piece its own space and identity. The sound needed to feel immersive, but not overwhelming,” says Slater.

“I didn’t begin with a fixed system or a specific spatial audio format in mind. Instead, I focused on what kind of listening the show might invite. What kind of presence did we want to create? What would help people feel more attentive, grounded, or curious?”

The visitor journey is punctuated by transition zones, which act as “sonic palette cleansers and physical sound buffers to help prevent bleed between neighbouring works,” says Slater. “But more than that, they became moments of spatial and emotional reset — a chance to shift gear, refocus, or just take a breath.

“Throughout the exhibition, I used spatialisation to create contrast — near and far, focused and diffuse — and to shape the rhythm of the experience.

“I approached spatial sound less as a technical feature and more as a compositional tool — a way of shaping how people feel and move in the space. The goal wasn’t to overwhelm or impress — it was to invite people into a slower, more attentive kind of listening.”

Integrating accessibility for Feel the Sound

Barbican Immersive worked with Mima, an accessibility design consultant, to develop the exhibition.

“Bringing people along on that journey can give us different perspectives and viewpoints that can make the overall experience better for everybody, and it was really important,” says Kemp. “I think more and more institutions are starting to take this on board and understand that if you want to bring a broader and wider audience in, you have to understand how you can cater to them properly.

“Mima brought people in with different lived experiences of accessibility needs and requirements,” says Kemp. “So, we’re catering to the full audience that will potentially come and experience this exhibition. And that was from the content to the interpretation, the lighting level, and what the journey feels like.”

For the sound design, Slater found that this collaborative approach offered opportunities to think carefully about providing multiple ways into the sound.

“That included subtitles for sound moments, tactile sound using transducers, and quiet zones for neurodivergent visitors,” he says.

“We need to move beyond a ‘visual substitute’ model of access, where subtitles or transcripts are seen as the only solution,” he says. “There’s huge creative potential in tactile sound, spatial sound that considers mobility and neurodivergence, or crafting experiences that don’t rely on traditional listening.

“The more diverse the design process, the more interesting and inclusive the results tend to be.”

Art & accessibility

Exhibits by Dame Evelyn Glennie and Raymond Antrobus exemplify this approach.

“Speaking with people like Evelyn Glennie, a percussionist from the deaf community, highlights the importance of getting people to understand what an experience of sound can be without listening with our ears. It’s a hugely exciting field to show and demonstrate.”

Glennie’s work, Teach the World to Listen, is on show in the Embodied Listening Playground. This newly commissioned film explores the difference between hearing and listening.

In addition, Raymond Antrobus’ sculptural work Heightened Lyric honours the sounds that have gone unheard. This work consists of seven kites that fly above the Lakeside Terrace and carry British Sign Language interpretations of poems on sound and its absence. The installation is inspired by the poet and author’s ‘high frequency deafness’ and confronts the gaps between the hearing and non-hearing world.

Feel the Sound and the future of Barbican Immersive

Feel the Sound marks a new focus for Barbican Immersive’s programming.

“Devyani Saltzman, our new director for arts and participation, has tasked our team with regular programming. So we’ll be doing year-on-year programming that can launch at the Barbican. Some of that will tour, and some of it will just be hosted at the Barbican Centre itself”, says Kemp.

“Feel the Sound is like a stepping stone to where we are going.

“It will form a bridge with the content we’ve done before, and a new focus to bring new audiences in. And with Feel the Sound, we’re looking more at being an audience-informed department. We are listening to audiences to think about the type of experiences they want or would like.

“This doesn’t necessarily mean we are being led by that, but we are listening to audiences to try and see how that can shape the type of content and experiences we create.

“This allows us to shift what we’ve been doing and understand the immersive market and the immersive space. And it doesn’t say we weren’t thinking about the audiences in the previous exhibitions. We were taking on these big topics, and I think we would still always do that.

“We are moving to more content creation. We’ll be doing annual projects and creating commissions. Not just within exhibitions but also in commissions that would be in the Barbican and potentially touring at some point. We’re thinking about collaboration with the broader sector for that.”