The Migration Museum explores how the movement of people throughout history has shaped the UK and its population.

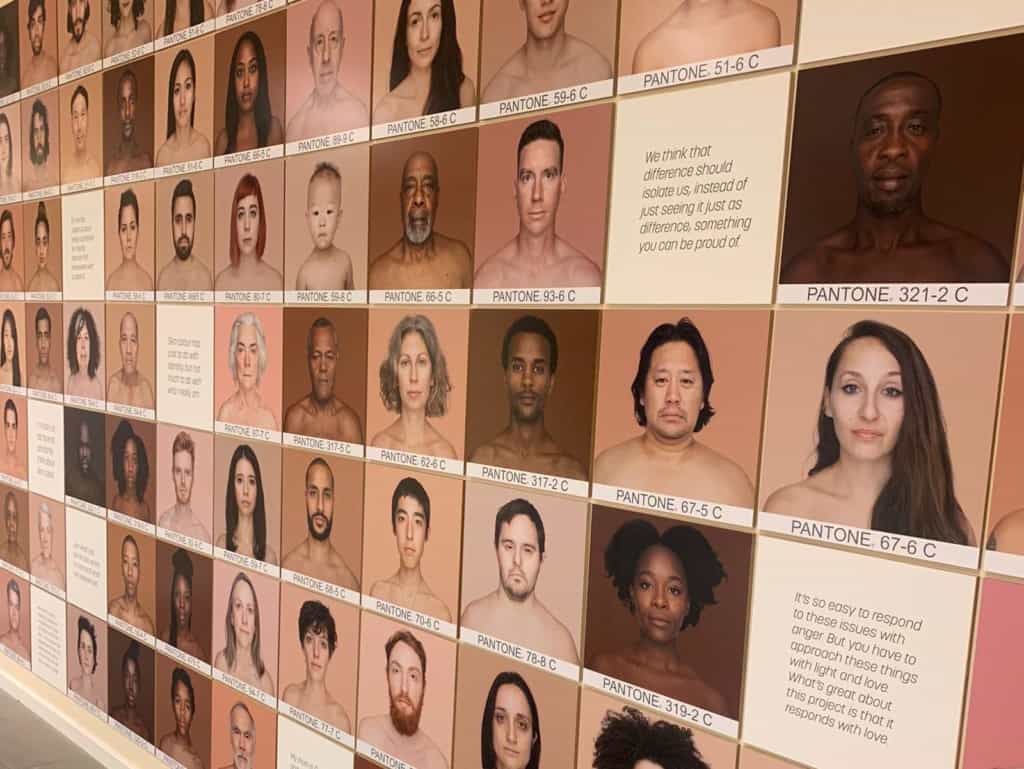

The museum opened with a re-staging of its acclaimed exhibition RoomToBreathe. This was shown alongside striking portrait photography series Humanae by Angélica Dass (pictured above). There were also events, workshops & more.

Sophie Henderson is the director of the museum. She previously practised as an immigration barrister, specialising in all areas of immigration, asylum and human rights law. Henderson provided training for the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association and was a volunteer adviser at Praxis.

In 2002 she became a judge of the Asylum and Immigration Tribunal. She was also appointed to chair appeals for the Social Security and Child Support Tribunal. A trustee of charity Our Hut, she has managed the Migration Museum Project full time since January 2011.

She talked to Blooloop about the Migration Museum Project, the genesis of the Museum, its evolution and the move to its new premises.

The start of the Migration Museum Project

Henderson found the Migration Museum Project compelling from the start:

“I really felt it. I picked up a book in a bookshop, Bloody Foreigners. This a history of immigration into Britain, written by Robert Winder, who is now one of the trustees. I read it and was slightly embarrassed at how much I didn’t know.

“I was fascinated, and struck by, by the importance of that story. Having visited Ellis Island shortly before that, and having been very moved, I felt that this museum was something that was missing in this country.”

She wrote to the book’s author, setting out those thoughts:

“He wrote back, and said: ‘That’s interesting because there is already a group thinking about setting up a migration museum.’ I had no idea that this group existed.”

She started attending their meetings.

“It was a small group, convened by Barbara Roche who was Minister for Immigration from 1999 to 2001. It was clear that if this was to progress, someone needed to start fundraising, and put in some time.

“So I took six months off work and started applying for funding, registering us as a charity, that kind of thing. That was in 2012. And it has all grown from there.”

Humble beginnings

At that point, the group had no funding:

“We constituted ourselves a charity; there were a few trustees. We had an initial goal of £5,000. With that, we set up a very rudimentary website, and we launched something called 100 Images of Migration. That was something that we could do for free.”

“With The Guardian newspaper, we asked people to send us an image that said something about migration. It was as simple as that.”

The response was a diverse and eclectic range of images. From digital snaps taken on smartphones to Magnum photographers.

“The breadth was wonderful. There are so many ways to speak about migration. We picked a hundred winners, and we put those on our website, and that was our first out output.”

First exhibitions

Sue McAlpine, who is now curator at the Migration Museum, but was at that point curator of Hackney Museum, put on 100 Images of Migration as a small exhibition.

“That was our first manifestation. We didn’t have our own space at that time. It was just a project that was growing I was the first employee.”

After raising a small amount of funding for an education programme, Emily Miller became the second employee, in 2013.

Henderson says: “We then started doing things. Emily started a schools outreach programme; visiting schools. Then we did something with the Southbank Centre in partnership with Counterpoint Arts.”

This was the Adopting Britain exhibition, curated by Southbank Centre in partnership with Counterpoints Arts. It ran at the Royal Festival Hall from April to September 2015. This aimed to highlight the personal stories of migrants and refugees, celebrating the contribution of migrant groups to Britain’s artistic landscape, and opening up a discussion.

“We didn’t curate it, but we contributed. Our 100 Images project formed the visual backbone to that exhibition.

Early collaborations

“We also had another little exhibition called Keepsakes,” says Henderson. “We popped this up in libraries and various places, including at the Southbank Centre.

“It was similar to 100 Images, in that the premise was that migration is relevant to every single one of us. We all have migration histories, so everyone can contribute a migration image.”

Equally, everyone can contribute a migration object. Sometimes the most exciting objects are the ones tucked away in people’s cupboards and drawers, with the stories attached. So we curated a few little collections of these lovely personal objects with wonderful stories attached.

“These, then, were two elements we contributed to Adopting Britain at the Southbank Centre, which was about post-war immigration to Britain.”

RE-THINK

This was followed by a collaboration with the National Maritime Museum.

“They had a community engagement space called RE-THINK.”

From June until mid-November 2015, RE·THINK focussed on Migration, one of the National Maritime Museum’s seven themes. The Migration Museum Project worked with the National Maritime Museum to engage with visitors, school groups and community groups.

“We were there for six months on the topic of migration, interacting with their collections. Those opportunities afforded physical manifestations where we could host events occasionally. We could hold workshops, and begin to get the feel of being a real museum.

Stories from Calais

“In 2016, we were offered an interim space for a very short period in Shoreditch, in Redchurch Street,” says Henderson. “It was a fantastic area with high footfall.”

“Our curators knew there was a story that they particularly wanted to tell. It was about the ‘Jungle’ refugee camp in Calais. This was in the run-up to the EU referendum. In fact, we took the exhibition down the day before the referendum.”

View this post on Instagram

The extraordinarily moving exhibition, ‘Call me by my name: Stories from Calais and beyond’ was at Londonewcastle Project Space in Redchurch Street. It ran from 2 June until 22 June 2016.

“It was an exciting moment for us. They put on a beautiful exhibition, telling the human stories behind the newspaper headlines. There were dismal headlines, every single day. And the anonymity of the people was striking.

“What we wanted to do was to humanise them. To bring out the incredible variety and warmth of the human beings who were living in these awful conditions. The camp in Calais, incidentally, was closer to us in London than Birmingham. But it was so anonymised and alien.”

Bringing stories to life

“The exhibition explored the intricacies and complexities of all the lives that passed through that camp. Largely through the amazing art that was produced there, and that we had brought to this exhibition in Shoreditch.

“It was a moving experience for us, and for visitors, it was a very visceral exhibition. Some of the art smelled of the fires in the camp.”

View this post on Instagram

While aware they were dealing with a politically charged topic, it was handled, Henderson feels, sensitively and well.

“Then there was a hiatus, while we didn’t have a home, and then we got this wonderful opportunity, two and a half years ago, to move into our fire station home.”

The Migration Museum at The Workshop

The Migration Museum at The Workshop, a maintenance building formerly used by the London Fire Brigade, opened on 26 April 2017. Its exhibits charted Britain’s history of migration, with references to early arrivals from the Celts and Romans.

“We were able to put on three exhibitions, in the two-and-a-half years that we were there.”

The first was a re-showing of Call Me by My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond in almost identical form. Along with 100 Images of Migration, this showed from April 26 to 30 July 2017.

There are moments in our history when something significant happens from a migration point of view. There have been hundreds of those moments

“And then we did another exhibition, [from 20 September 2017 – 9 September 2018] which we loved, called No Turning Back: Seven migration moments that changed Britain. It was bookended by 1290, the expulsion of the Jews, and Brexit. There are moments in our history when something significant happens from a migration point of view. There have been hundreds of those moments.

“We picked seven and looked at them. Each had echoes, resonances, that made them relevant to us today.

Each one is a talking-point. You couldn’t look at the expulsion of the Jews in 1290, for instance, and not think about current conversations about antisemitism. These things are perpetually relevant. And this was a way of getting the sense of the sweep of the story across, by focusing on those few moments.”

Room to Breathe

Room to Breathe was the third exhibition in this location, explains Henderson:

“With each of our exhibitions, we aim to try something new. The Calais exhibition was a very hot and current political topic. No Turning Back was a look at history; at both immigration and emigration, to get across the scale and the breadth of the migration story.”

“Then we wanted to do something else. Something more personal and immersive, about human experiences and the present day.

“Room to Breathe is about the actual process of people arriving and settling into a new country. It is told through a series of rooms. There is a bedroom, a kitchen, a barbershop, a classroom, and an artist’s studio. They are all spaces in which people find their feet and express their humanity. These are universal stories.”

A human perspective

The exhibition showcases the stories of around 150 people as they arrive in Britain.

“But the themes are universal,” says Henderson. “They are about people arriving in new situations and new circumstances. They are very accessible on a human level, for everybody, because these are human stories.”

The bedroom is often the first space where someone arriving after a long journey to a new country can relax. The bedroom space in the exhibition is inspired by the story of an immigrant from Jamaica, who fought in the RAF in the Second World war.

“His daughter had got in touch with us, and given us his letters and sketchbook – he was an artist. We recreated his room, and made facsimiles of all his letters, and had a facsimile of his sketchbook the table. The idea is that you can come into the room and read his letters. You can flip through his sketchbook, and feel what it might have been like to be him.

“There was a picture of him on the wall with his daughter. He went on to work for London Transport. You could open the wardrobe and touch his British Rail coat.”

Real people

Installations like this help to create an emotional connection. These are real people, with real stories. The stories, the humanity, are universal.

“In the kitchen, the ingredients on the shelves looked perfectly ordinary. But if you took down a bottle of ketchup and turned it around, it would have someone’s story on the reverse”.

The exhibition featured 150 stories, told in a variety of immersive, experiential ways. She says: “I think people did find that engaging and were touched.

“In the schoolroom, another place where people will often find themselves when newly arrived in a country, there are reminiscences about what it’s like to be the only child in the class who doesn’t speak English. Or being the one who brings a packed lunch which looks and smells different from everybody else’s.

“We have exercise books on the tables where we invite people to leave their own memories. Hundreds of people responded very viscerally because the exhibition moved them.”

Reaching new audiences

Reaching new audiences is a perennial challenge for institutions like the Migration Museum. The people whose compassion and understanding it would be most rewarding to engage might not be the people coming to exhibitions.

Henderson feels the museum’s new location may address this:

“I think this is our moment. Being slap bang in a busy shopping centre feels like the most amazing opportunity.”

“It is true that people who have sought us out before have been slightly self-selecting. For instance, those with a predisposition to show interest in the themes we explore. People who are, broadly, pro-migration.

“Being here in a shopping centre, we are not asking people to come to the museum, but are bringing the museum to people. The shopping centre’s mass annual footfall is 15 million. This is an extraordinary opportunity to engage people who are just coming to do their shopping, whoever they are and whatever that is.

“Early indications are positive. On average we had 600 visitors a day since opening. And we have had really warm responses. People have said ‘This is so important’, and ‘We think what you’re doing is relevant.’

Local and national connections

“There’s an incredible sense of local pride in the mission,” says Henderson. “While it is still early days, it seems like a real moment to experiment with bringing this museum to completely new audiences.”

Migration stories abound across the country. Museums and similar institutions nationwide are keen to tell these stories:

“People relish the opportunity to come together and discuss ways of doing this. So we piloted something called from November 2016 to November 2017, called the Migration Museums Network.”

“This was a way to enable curators, exhibitors, academics and other interested parties to come together to discuss best practice and ways of bringing out migration stories within museum and heritage collections nationwide.”

The aim of the network pilot, funded by Arts Council England and Paul Hamlyn Foundation, was to increase and improve outputs associated with migration and related themes in museums and galleries across the UK.

Future plans for the Migration Museum

“We now plan to convene six such Network events nationwide over the next 18 months or so. We want to build on the pilot that we did in 2017/8.

She adds, in conclusion:

“Much of our public engagement focusses on ‘everyday’ migration themes like football (we run an annual football and basketball tournament with local partners), family history (we held our first family history day in 2019 in partnership with National Trust, Black Cultural Archives, National Archives and many other partners) and food – we hosted a series of cookery classes given by migrant and refugee chefs at the museum in partnership with social enterprise Migrateful.

We’re sharing more stories from #RoomtoBreathe so you can enjoy the Migration #Museumathome

Lola: “I knew London before I came here because I read books about it. I started reading English 30 years ago – at first simple books, then more complicated ones…” 1/3 #AllOurStories pic.twitter.com/iiMLOVNeKX

— Migration Museum (@MigrationUK) March 27, 2020

“In Lewisham, we are continuing all these themes. We are reaching out to a very wide range of community groups. For instance, we are hosting monthly coffee mornings with facilitated workshops. This is so that local groups can get to know both the museum and each other.”

The Migration Museum and COVID-19

Like all other arts and cultural institutions in the UK, the Migration Museum temporarily shut its doors in mid-March due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Henderson and the team are still finalising their re-opening plans in response to government guidance and the ever-changing public health situation, and in consultation with the management of the shopping centre where it resides.

The Migration Museum is planning to reopen in the autumn with the launch of a new exhibition, Departures, exploring 400 years of emigration from Britain to coincide with the 400th anniversary of the sailing of the Mayflower to North America this year.

It is also working on a digital exhibition exploring migration and the making of Britain’s National Health Service, and a community-focused offer for local residents. In the meantime, its 100 Images of Migration and Keepsakes exhibitions can be explored online via its website.

All images kind courtesy of the Migration Museum