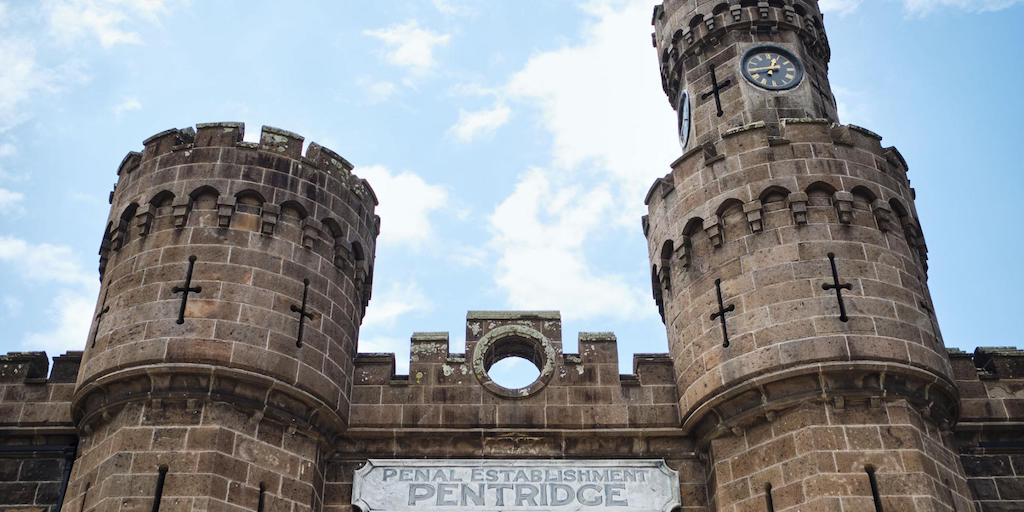

Art Processors, the experiential design consultancy, recently worked on a project to produce immersive visitor experiences at Pentridge Prison. The reimagined tour combines an exploration of the site’s history with powerful first-hand accounts from former inmates, prison officers and clerics. The old B Division, H Division, rock-breaking yards, and former Warders’ Residence are all included in the visitor journey.

This project combined the firm’s comprehensive expertise in exhibition design, location-aware audio, and creative technology, and it is based on the in-depth research and nuanced narrative that was demanded by the subject matter’s complexity. Art Processors provided experience strategy, exhibition design and interactive media services for client National Trust of Australia (Victoria) in Coburg, Australia.

Presenting an accurate story

In contrast to the contemporary reconstruction of the larger complex, the company’s interpretation of Pentridge Prison completely embodies the National Trust’s ambition to ensure that the heritage of the site is not disregarded or forgotten. Visitors are prompted to reflect on the nature of retributive justice as a result of the experience, which also leaves those willing to confront some of the most gruesome episodes in Victoria’s criminal history with a complicated mix of emotions and unanswered questions.

Any interpretation of penal and criminal history is necessarily complex. Many well-known convicts were incarcerated at Pentridge Prison, but the team purposely avoided repeating tired stories. Instead, they sought to present an accurate portrait of daily life in Pentridge, as related by those who lived it—from the depressingly routine to the unsparingly cruel.

However, this inevitably brought up emotive issues. For instance, were the crimes that prisoners commit relevant to the stories that the team wished to tell? Could they really anticipate that tourists would look past these acts to appreciate the human experience of incarceration? What responsibility does the attraction have to visitors, given the upsetting nature of this content?

Project challenges

Because the old prison is also subject to a Heritage Overlay and is listed on the Victorian Heritage Register, it also presents additional difficulties to coordinate exhibition design and technological fit-out with the existing base build. The prison’s original design is incompatible with a place intended for display and exploration, although it naturally produces a sombre atmosphere appropriate for such a trip.

Art Processors works under the guiding idea that the land itself always has a compelling narrative when it takes on a project centred on landmarks and sites. The Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation’s unceded lands are where Pentridge is situated and the team saw the importance of recognising that the connection between First Nations people and incarceration in Australia is a deep wound that still has an impact in the present day.

A connected narrative

The company was first hired to work on Pentridge’s redevelopment based on a Master Plan that was already in place and concentrated on the prison’s 19th-century past, but this was expanded into the 20th century after negotiations with the National Trust.

This allowed the team to connect the history of the location itself, including the land before the jail was built there in 1851, through a time in recent memory when the prison was shut down in 1997. This in turn gave visitors more places to start learning about a larger range of subjects throughout time, helping to provide a complete picture of Pentridge’s history as a jail from beginning to conclusion.

Art Processors conducted official interviews with more than a dozen former inmates, prison employees, clerics, attorneys and other people who spent time in the facility. Pentridge Voices, a volunteer research initiative devoted to preserving the history and recollections of the prison, organised these interviews.

The team was grateful to the interviewees for sharing their stories but also realised that some of these stories might rekindle old anguish for some visitors. For this reason, they chose not to include specific occurrences, even though they didn’t want to minimise the harshness of these inmates’ experiences. Many prisoners’ tales turned out to be too complex to fully describe in a comparatively limited time.

Consultation with the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation

“The modern-day Pentridge redevelopment has all the trimmings of normal daily life—a cinema, a grocery store, a playground,” says Sam Doust, group director of creative services at Art Processors.

“But it’s also a place where people were executed, committed suicide, were in for heinous crimes of one sort or another—or just for being drunk—over a period of 150 years on Wurundjeri Land. Unless you interpret that long penal history, and acknowledge the much longer Indigenous identity to the land, you are forgetting. You are whitewashing. We felt this project was a chance to ensure that didn’t happen, and bring integrity and truth-telling to this place.”

Art Processors consulted the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation about the exhibition’s content and how the tours would be conducted. The jail renovation and audio experience include artwork and narration by First Nation Elders and representatives, including Uncle Bill Nicholson, Chris Austin, Les Griggs, and the late Uncle Jack Charles. Their contributions help to put the strained relationship between First Nations people and the criminal justice system into perspective.

The team had the honour of collaborating with Uncle Jack Charles, who sadly passed away a few months before the project was finished. Art Processors appreciate the family’s permission to use his voice in the audio narration.

“Uncle Jack was a gentleman, a raconteur, and phenomenally generous,” says Kate Chmiel, senior content developer. “He offered a unique perspective on Pentridge because he saw it as a bit of a reset in life. He was loved and respected in there, and later on he became such an important mentor to young Indigenous people in prison. We have a lot of love, respect, and gratitude for being able to talk to and spend time with Uncle Jack.”

Working with the architecture

The prison’s bluestone architecture turned out to be helpful for the firm’s technology despite its constrained spaces. In order to determine which cell narration to play for the immersive audio experience, Bluetooth beacons are used to triangulate the visitor’s location, with bluestone acting as a barrier against ‘signal bleed’ into adjacent cells.

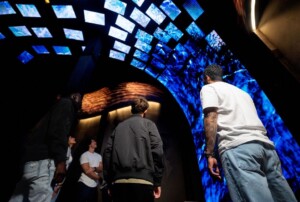

Allowing the bluestone to be part of the story was an important conceptual motif. However, this surface’s dark and abrasive texture made it difficult to project images directly on it. To provide the most clarity, the team tested with various projectors and high-contrast monochromatic graphics.

Additionally, there are a number of collages on the walls that incorporate pictures of prior inmates and incorporate narrative into the design of the prison. Art Processors was given permission to restore one cell to its original 19th-century state, revealing the bluestone that the inmates themselves had excavated, in order to reproduce the starkness of the “separate and silent” regime of nineteenth-century confinement.

A vivid feeling of contextual dissonance is provided during Pentridge Prison tours. The redevelopment of the complex includes a variety of modern suburban conveniences, yet the earth and bluestone that make up these features bear witness to the historical violence and cruelty of the jail.

Multimedia exhibits and an audio tour

The tours begin in the former Warders’ Residence, which features multimedia exhibitions and artefacts that provide a preview of what guests can expect to see and hear. Visitors can choose to take “H Division: Unlocked” to confront the most horrifying aspects of the wing, “B Division: Pentridge Through Time” for a thorough voyage into the history of the location, or both tours one after the other. Each lasts 90 minutes.

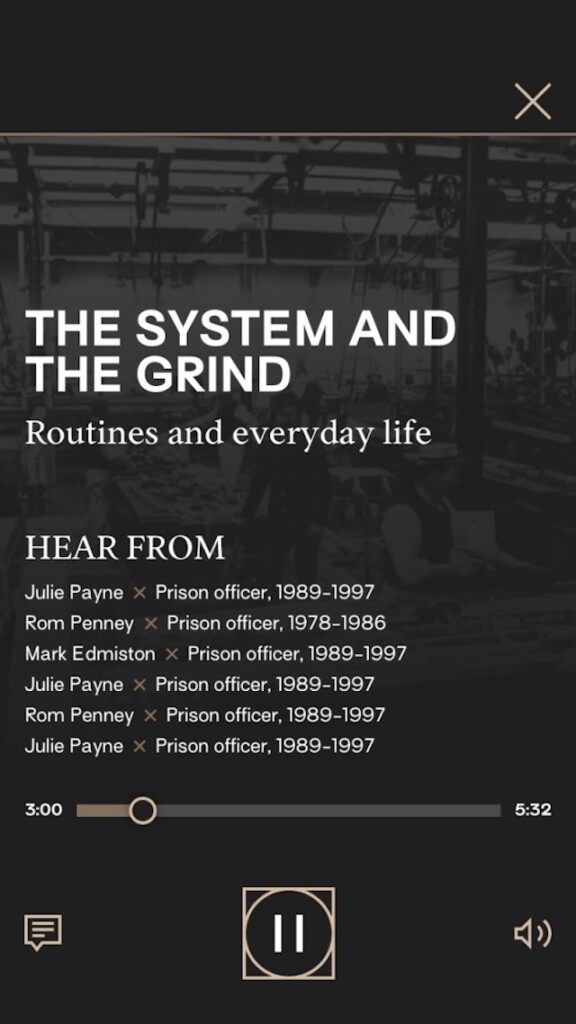

Art Processors’ audio devices provide visitors with a location-aware and immersive eyes-up experience as they explore the prison after an introduction from a National Trust guide. Each area explores a different subject—escapes, women in Pentridge, daily routines and punishments, to mention a few. The device plays narration from people who have experienced these events as the visitors enter the cells.

Inmates are depicted in some cells as video projections to go along with the narration, while other cells are set-dressed to depict the prison’s living conditions. Some cells have been restored as similar to their original state as feasible, while others include object collections.

Various cells are set-dressed to faithfully render the austere living conditions of the prison during its operation, while others feature inmates as video projections to accompany the narration. Others feature object collections, and some specific cells have been preserved as closely as possible to their original condition.

A deeply personal experience

“From the beginning of this project, we’ve done a lot of thinking—and we may not necessarily have the answer—on the purpose of retaining a prison as a public space after its closure,” says Chmiel.

“There are the historical aspects, of course, where it’s fascinating to glimpse a world that’s very distant from our own. But I’m hoping people will think about the bigger question of why prisons exist, and how we choose to treat people who have transgressed what we consider to be legal or condoned behaviour. Prisons are closed-off spaces and most of us are unaware of the conditions inside, so it’s very easy to not think about the people within them.”

Doust adds:

“I’d like visitors to leave the tour having been touched by the complexity of this place, and being capable of understanding the modern redevelopment of the site within the context of its difficult past. To take all that and juxtapose it with what’s there now—a built environment for a modern, peaceful, daily life.”

Last month, Art Processors joined forces with The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art to reimagine the Bloch Galleries through an innovative immersive art experience.