Andy Moore, director of science, education and training at Colchester Zoo, spoke to blooloop about the zoo ’s history, its evolution, its conservation work, and its transition as it prepares to become a charitable trust and zoological society, Colchester Zoological Society (CZS), from 1 January 2025.

A zoo conservation education manager with 25 years of experience across a range of departments, including animal, commercial and education, Moore has been with Colchester Zoo for ten years, enabling visitors to the Zoo to gain a comprehensive understanding of its work, transforming them from passive visitors to active supporters.

Zookeeping & education

Moore was born into a zookeeping family. His father was a keeper at Bristol Zoo, and so, for a shorter period, was his mother. He studied primary school teaching at university. However:

“I was working with lemurs and all sorts of wonderful animals as a part-time primate keeper at Bristol Zoo, and I decided to become a full-time zoo zookeeper.” He worked with primates for the next eight years or so:

“But that desire to educate was quite strong. So, 20 years ago, I became an education officer at Bristol. That has been my path since, focusing on environmental education.”

He went on to work at Twycross Zoo and then at Whipsnade as manager of visitor engagement and interpretation. Moore has been at Colchester Zoo for around ten years and has been the director of science, education, and training since August 2023.

“My interests centre on saving wildlife, but especially on how zoos are a shop window onto nature. I’m interested in exploring how we can use that shop window to talk about the issues facing wild animals and habitats and, more importantly, how we can bring people along with us in what we want to achieve, what techniques and methods we can use to involve people in changing not only hearts and minds but behaviours. It all comes back to humans and what makes humans tick.”

The origins of Colchester Zoo

Colchester Zoo was founded in 1963 by the zoologists Frank and Helena Farrah, who had previously run a zoo in Southport, Lancashire. Helena became one of the first women to be a curator in Europe. In 1983, the Farrahs sold the zoo to their niece, Angela, who had spent her childhood at their previous zoo in Southport, and her husband, Dr Dominique Tropeano. They still own the zoo, though, in 2025, it will become a charitable trust, Colchester Zoological Society.

“There were loads of challenges,” Moore says. “There was the hurricane in 1987 that blew half the zoo away and the outbreak of the foot-and-mouth disease in 2001 when all the zoos closed, there was the financial crash of 2007-2009, and then there was the closure of COVID-19. The way all these challenges were navigated is a testament to the Tropeano family. From the early 80s, with very little investment, they built the institution into one of Europe's leading private zoos.”

When the zoo becomes a charity on 1 January 2025:

“We’ll still be Colchester Zoo, but Colchester Zoological Society will allow us to access different pots of funding for conservation work in the UK and overseas, which is exciting.

"The aim now is to encourage our visitors to develop their journey of conservation with us, not just by purchasing memberships or donating money to us to do conservation on their behalf in the UK and overseas – though we’d love them to do both, of course – but by volunteering - to count endangered moths in North Essex, for instance, or by getting involved in any of so many different ways.”

A new chapter

Colchester Zoo’s story is a microcosm of the evolution of the approach to animal welfare over the decades. Moore references Gerald Durrell, the naturalist, writer, environmentalist, and founder of Jersey Zoo:

“Not long before he died in 1995, Durrel said a good zoo should be like an octopus with its very intelligent brain as its headquarters and all those wonderful tentacles spread out all over the world, helping animals wherever they can. I used to have the quotation up on my noticeboard.”

Adding some texture on the decision to become a charity and the opportunities this affords in terms of partnerships and conservation initiatives, he says:

“We want to reveal a lot more of the work that we do. Traditionally, in the UK, a visit to the zoo is a family thing, generally in the summer. It’s a social occasion. Of course, we want to facilitate an enjoyable day. But actually, it will be an enjoyable day engaging with the different topics that we have to talk about.

"There are a lot of depressing things out there in nature, but we don't want people to be depressed on their journey with us. We want them to feel empowered and positive about not only what the zoo does in terms of welfare and conservation in the UK and overseas but also how they can get involved at home. We want them to realise that, as humans, we are the cause of some problems – but we are also the solution to some of those problems.”

In short:

“By being a charity, we want to open up more of that work to people. We are a strong community zoo. However, we want to make that even stronger and have many ideas about how to do that.”

Conservation at Colchester Zoo

Concerning conservation initiatives, he adds:

“Like all zoos, we think globally and act locally. We have local engagement programs with school groups to come and learn surveying skills for environmental monitoring. We have our own nature area on site, highlighting local species. There are grass snakes, and wild otters visit it.”

As an educationalist, Moore’s focus is on skills:

“I’m a big STEM ambassador, so we try to ensure the kids get excited not only by the wildlife but by the techniques there to help us monitor wildlife. We have a camera trap loan scheme and lend camera traps and resources to schools for a term. The kids program the camera traps, then do a Dragon's Den–style analysis of which camera trap is better. They also assess the potential sites to set up a camera trap in terms of the good and the bad before analysing wildlife behaviour.

"We are trying to build up a picture of what wildlife is on our school partners’ grounds.”

Supporting endangered moths

Another initiative centres around an endangered moth species:

“We have been working with the Fisher’s Estuarine Moth for the last 15 years.”

The project focuses on breeding and releasing the species into newly created habitat sites around Essex. Since the species is completely reliant on Hog’s fennel as its sole caterpillar food plant, the initiative also involved propagating the plant species, which is also threatened, in this case, due to rising sea levels.

Since 2006, alongside the creation of a network of new habitat sites along the Essex coast, Colchester Zoo has been breeding the moths and providing batches of eggs annually for release onto these sites. In the spring of this year, the zoo released the last 13 batches of moth eggs, each containing between 20 and 100 eggs, at habitat sites at Brook Country Park, Clacton-on-Sea, the final move in a successful repopulation project.

Additionally:

“We have core partner projects that are working worldwide in different areas. Our charitable arm, now ‘Colchester Zoological Society’ (CZS), previously called ‘Action for the Wild’, is responsible for this sort of work. For example, we support an elephant orphanage in Zambia not just with money but with support. We are on the end of a phone call to advise on any community outreach they might be doing in the area.”

Decolonising the zoo sector

Moore’s academic background in education has a focus on history. He says:

“I'm fascinated by Britain's influence on the world, good and bad, and I'm interested in how we go forward with that relationship. For the last 60 years, conservation has been colonial: people from Europe and North America going to Africa or wherever and saying, ‘Ah, we've got the solution for you.’

"I want to have a true partnership with organisations. It’s about working together.”

This, he contends, is the new frontier in conservation:

“We need to reflect on the fact that education networks within Europe and the UK might have access to better resources in many cases, so that should be exploited. Inevitably, though, the people living on the ground in the countries where these animals are located need to be the ones coordinating and directing these things.

"We have partnerships in Zambia. The Elephant Orphanage Project is one. It has a mission to rescue, rehabilitate and release orphaned elephants - often orphaned by the illegal ivory trade - into protected reserves.

"We also raise funds for Save The Rhino for specific purposes, such as purchasing small aircraft for rangers to monitor poaching and rhino numbers.”

Elephant alerts

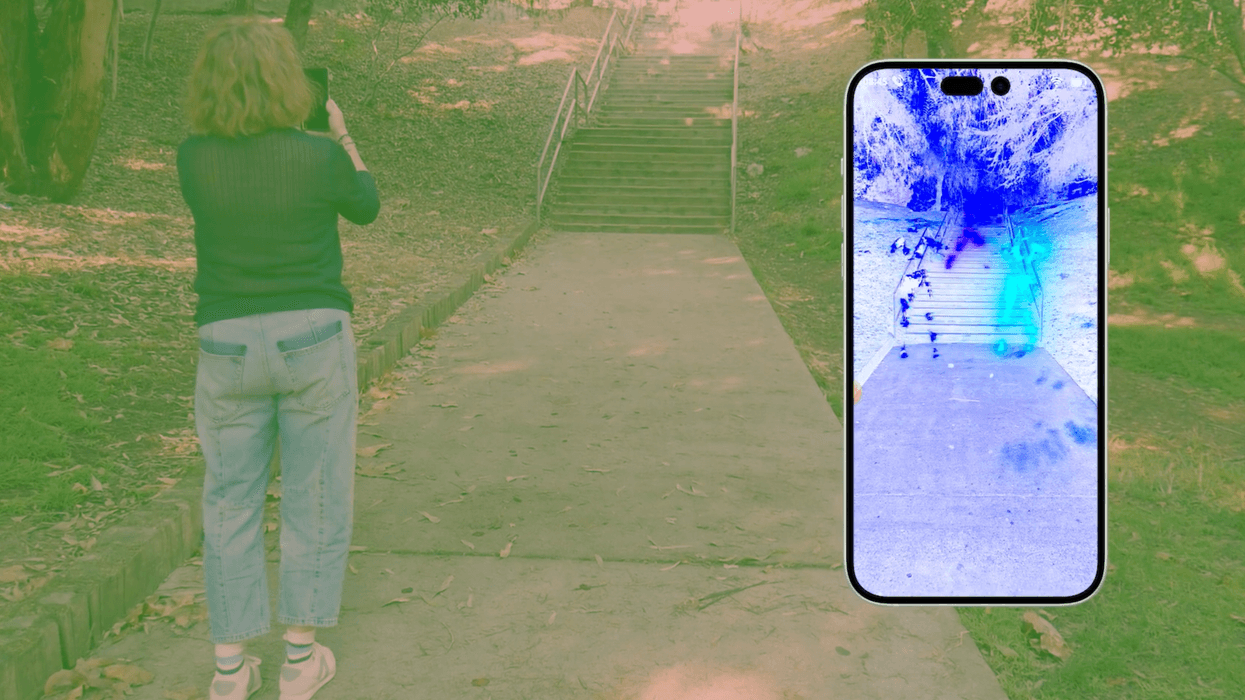

Colchester Zoo has recently been collaborating with ZSL Whipsnade Zoo on a tech-based project using thermal cameras to identify the heat signature of elephants, spearheading the creation of the HEAT (Human-Elephant Alert Technologies) Project.

"Elephants are wonderful. But if you live alongside them in rural Kenya or Sri Lanka, they can be dangerous to people and can damage or destroy crops. Human-wildlife conflict is a fact of life.”

This project is part of an initiative to mitigate such conflicts. Cameras around Colchester Zoo’s sizeable African elephant enclosure take thermal pictures of the animals engaging in different activities: eating, sleeping, playing, being trained and interacting with people, relaxing, and reaching for food.

The thousands of images produced are then used to train the camera technology to recognise an elephant. The images of the African elephants can be compared with pictures of the Asian elephants at ZSL Whipsnade to detect the difference in size and shape between species. So far, the camera technology can confidently identify elephants and people at a distance of up to 30 metres.

Moore adds:

“The tech is being trialled in Asia. The units are set up at the edge of communities. Despite weighing around five tons, elephants are silent, but the units identify them, then send a text message to everyone in the communities to say, ‘Stay indoors’. The community can then set off a firework to scare the elephants away. The outcome is that the community isn't harmed, the elephants aren’t harmed, and the conflict has been mitigated. The trial in Africa will happen next year.”

Colchester Zoo & African hunting dog conservation

He turns to the jewel in the zoo’s conservation crown, an initiative focusing on Africa’s endangered hunting dogs (lycaon pictus):

“Overseas, Colchester Zoo owns 14,000 acres of lowland belt in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa: the UmPhafa Private Nature reserve. It was four former farms that we purchased 20 years ago and put back together as a fenced reserve.”

Historically, around 35 mammalian species are thought to have potentially occupied the region where the reserve is now located. Many of these were subsequently excluded from the area through overhunting, habitat fragmentation, and competition with livestock.

Now, the habitat, rich in grasses, flowers, fungi, and trees—including the iconic UmPhafa Tree—is home to giraffe, zebra, rhino, buffalo, 13 varieties of antelope, 11 carnivore species, 277 bird species, a plethora of invertebrates, reptiles, and amphibians, four types of mongoose, three wild pig species, and African Hunting dogs.

Since 2017, UmPhafa has collaborated with the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) to hold and bond wild dogs as part of the African Wild Dog Range Expansion Project, which implements reintroductions of African wild dogs across southern Africa. The project, which is working to develop a second viable population outside the Kruger National Park, increasing safe space, population numbers and pack numbers, today boasts a population of over 300 wild dogs across 1.3 million hectares of safe space.

“About a thousand hunting dogs are left in Africa,” he says. "They can no longer move naturally between reserves because towns, cities, and farms are in the way. They get shot because they eat domestic livestock. Through this initiative, we know the background of all the hunting dogs in private reserves in South Africa. So, we can manage a breeding programme.”

An award-winning approach

Sometimes, dogs living wild on the reserves can be evicted by their packs.

“We then take the ones kicked out of their groups on other reserves. Using some of the techniques we've mastered in zoos over the last 40 years, and that we're now using with wild animals, we can jump in, socialise them, and they go off to other areas.”

In 2021, the UmPhafa Private Nature Reserve, in conjunction with the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT), African Parks, and Malawi’s Department of National Parks, took part in the historic relocation of the African wild hunting dog from South Africa to Malawi, a major international effort to conserve the endangered dogs. In 2022, Colchester Zoo won the BIAZA (British Irish Association Zoos & Aquaria) 2022 Gold Award for Field Conservation for its efforts in bonding African Wild Dogs on the UmPhafa reserve.

The human piece of the puzzle is inevitably key to successful conservation efforts. He adds:

“We are starting to get into community engagement in South Africa, as well. That's a new horizon – we want to make that connection between conservation and community engagement.”

There are, he concedes, mistakes, false steps and learnings along the way. However:

“That’s what innovative conservation is about.”

Ecotourism

Ecotourism is an emerging trend that he believes has the potential to do a great deal of good.

“We might say the only value wildlife should need is to be these wonderful, sentient beings. In reality, however, wildlife often needs an economic value if it's going to be protected. A great way to do that is through tourism.

"I was recently on a holiday in Costa Rica, which is famed for its good approach to conservation. I saw it everywhere, among the schoolchildren I met; everyone was very protective of wildlife. And it underlined the fact that wildlife lives alongside us. There were leafcutter ants everywhere; we saw raccoons; there were howler monkeys in our hotel.”

However, where it is done poorly, tourism can do significant damage.

“Upwards of 95% of the world's wildlife doesn't live in a protected area. It lives on farmland; it lives among us. The challenge is finding a balance in terms of our impact on it.

“The developing world is starting to do this sort of tourism much better. 20 or 30 years ago, I'd say ecotourism was part of the problem in some areas. Now, good ecotourism provides jobs to the local community, meaning it’s in their interest to look after the wildlife, and conflicts are mitigated. A lot of countries are implementing strict laws."

The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) Criteria serve as the global standards for sustainability in travel and tourism and are used as a basis for certification. The criteria are designed to be adapted to local conditions and supplemented by additional criteria for the specific location and activity. They are the minimum that businesses, governments, and destinations should achieve to approach social, environmental, cultural, and economic sustainability.

Storytelling at Colchester Zoo

In the 1990s, Colchester Zoo had a focus on African species:

“When the bottom part of the zoo was developed in the mid-nineties, it was African-themed: African rainforest, African savannah. The mixed paddock had African elephants, giraffes, rhinos, cranes, ostriches, and zebras."

Now, much of the world is represented.

Concerning storytelling, Moore says:

“Traditionally, zoos were in taxonomic arrangements: the lion house, the reptile house. For the last 40 years, though, our ethos here has been to have some flagship animals – lions, tigers, bears, for instance - with the supporting species in exhibits around them. We have weaver birds, tortoises, African fish species, African vultures, and African snake and reptile species in the African building.

"Using those smaller, supporting species around the flagship species works well, enabling us to tell better stories about the habitats."

For the future, he adds:

“I hope we can explore not just geographical and even taxonomic exhibits but issue-based exhibits. For instance, a couple of zoos in Germany have an animal house they have converted into the IUCN red list of endangered animals. The exhibit talks about how we measure endangerment and the tools that we use."

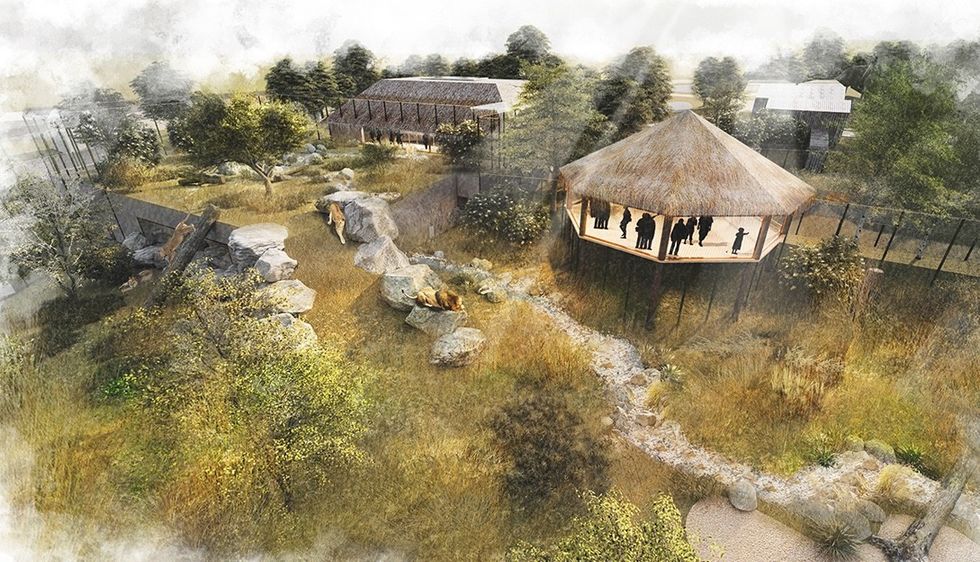

New habitats

The zoo’s long-term development plans include a new African lion habitat. This will incorporate several immersive viewing opportunities. The team has been working closely with architects at Dearadh Zú to develop an innovative, exciting habitat inspired by the rich biodiversity of the African scrub and Kopje habitats.

The development will comprise approximately 3000 square metres of naturalistic lion habitat, complete with scrubland planting areas, mature tree cover, rocky outcrops, dens, and water bodies, all of which will encourage natural behaviours. There will be a new lion house, outdoor habitat, and indoor viewing area. There will also be a themed African Boma Village complete with a new catering outlet, toilet, and play provision.

The design maximises space so the lions can climb, play, and engage in natural behaviours. The Colchester Zoo team, keeping the institution’s ‘green zoo’ mission at the core of the project, has been working closely with ecologists to ensure they are conserving and enhancing existing landscape and biodiversity on site, prioritising sustainability and green technologies and ensuring BNG targets are delivered.

The project showcases the synergy between animal welfare, sustainability, and the visitor experience to create optimal outcomes.

A future vision

Once the habitat is developed, a new pride will be introduced so that Colchester Zoo will become part of the breeding programme in the future. The African lion is listed as ‘vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Colchester Zoo is currently home to Bailey, a 17-year-old male lion who has outlived his companion lioness, Naja.

The current Lion Rock area will be the next project on the agenda. At this point, the plan is to refurbish it into an alternative Gelada baboon habitat. This, in turn, will offer the opportunity to revamp the current Gelada Plateau, transforming it into an aviary for the Ruppell’s Griffon vulture and offering a brand-new visitor experience.

Relocating the vultures will create additional space for the Kingdom of the Wild habitat, providing more room for the giraffe, rhino, ostrich, kudu, zebra and crowned crane to roam.

The zoo says this is just the start of the journey towards its future vision. To bring this dream to life, Colchester Zoological Society will need the continued support of loyal visitors and new ones.

Colchester Zoo aims to change public perception of zoos

In June 2023, speaking on the occasion of the institution’s 60th birthday, Dr Dominique Tropeano pledged that Colchester Zoo would never become a theme park.

Moore says: “We’re very much a zoo, and we remain a zoo. Part of this entails bringing people along on a positive journey regarding the change of perception around the word ‘zoo’. I sit on committees for BIAZA. I sit on the education committee. Sometimes, people say, ‘Maybe we could call ourselves a conservation park or a wildlife centre.’"

"We’ve seen this happen in America. The Bronx Zoo changed its name to the Bronx Wildlife Conservation Society. But what is a wildlife conservation centre? Globally, everyone knows what a zoo is. I accept that it doesn't lie positively with everybody. But it's down to us in the zoo to change that perception as best as possible regarding our welfare and conservation work.

"We will always be a zoo. And we will continue, with colleagues worldwide, to develop what the perception of a zoo is.”

Immotion CEO Rod Findley and VP of Content Ken Musen celebrating their Lumiere win at the 16th Annual Lumiere Awards, held on 9 February at the iconic Beverly Hills Hotel.

Immotion CEO Rod Findley and VP of Content Ken Musen celebrating their Lumiere win at the 16th Annual Lumiere Awards, held on 9 February at the iconic Beverly Hills Hotel.

Zoo Aquarium de Madrid

Zoo Aquarium de Madrid Faunia

Faunia