By Sean Mannie, Marwell Wildlife

All of us who work in zoos and aquariums will have recently empathised with our colleagues at Whipsnade Zoo, following the hugely difficult decision to euthanise two brown bears after a breach of their enclosure by a fallen tree. Regardless of role, we all understand the weight of responsibility and duty of care that we owe to our animals.

This tragic incident highlights, as have others before it, the importance of emergency planning, especially given the very unique nature of the zoo environment, with animals and humans constantly in close proximity.

The importance of emergency planning

Emergency planning can be a tough subject to address. It means facing up to difficult situations you hope will never happen and expending precious time and resource into planning you may never need to use.

Being honest about what could go wrong is never easy for any business. But we need to be open and brutally honest about our weaknesses and consider carefully how best to deal with them. There are many competing demands for investment. So, we naturally think twice before expending effort and cash on infrastructure we hope never to use.

For many, the most obvious output from emergency planning is, not surprisingly, a plan. For me, a plan can always have some value – as a reference work and store of knowledge. However, when things kick off, is anyone really going to ask the world to stop while they get their lever-arch file from the office?

This is where the difference between planning versus plan comes into play. No matter how detailed your plan, it assumes a set of circumstances and provides defined responses.

Useful maybe, but as a 19th century Prussian General ( Helmut von Moltke the Elder for the history buffs) is often paraphrased as saying ‘no plan survives beyond the first contact with the enemy’. In my experience, that enemy is the unexpected and random event – or person or animal - that trips up your carefully crafted assumptions and wrecks your diligently prepared responses.

Dynamic thinking

For me, planning is a different beast. It is a more agile process that encourages dynamic thinking, constant learning and flexibility in response. For the most likely risks, such as animal escapes, we drill and practise, as I know our colleagues at Whipsnade and others do, regularly changing the scenarios, adding new variations and involving everyone within the site, as well as external agencies.

Then we debrief afterwards – what went well, what fell over? No blame, no foul, but a bit like Artificial Intelligence, we learn a little bit more with each exercise. As we learn, we seek not just to improve our responses, but our working environment. And we make that risk just a little less likely to happen.

We all have to accept that you can’t completely eliminate most risks. If something does happen well trained and confident people will react more instinctively. This is because they will have already considered, weighed up and tried the options. Now, they are much more likely to make the difficult decisions, quickly and decisively. That is when the emergency planning investment really pays off.

I will leave you with another saying from history that has never lost its value to me in my everyday work: the biggest risk is to do nothing at all.

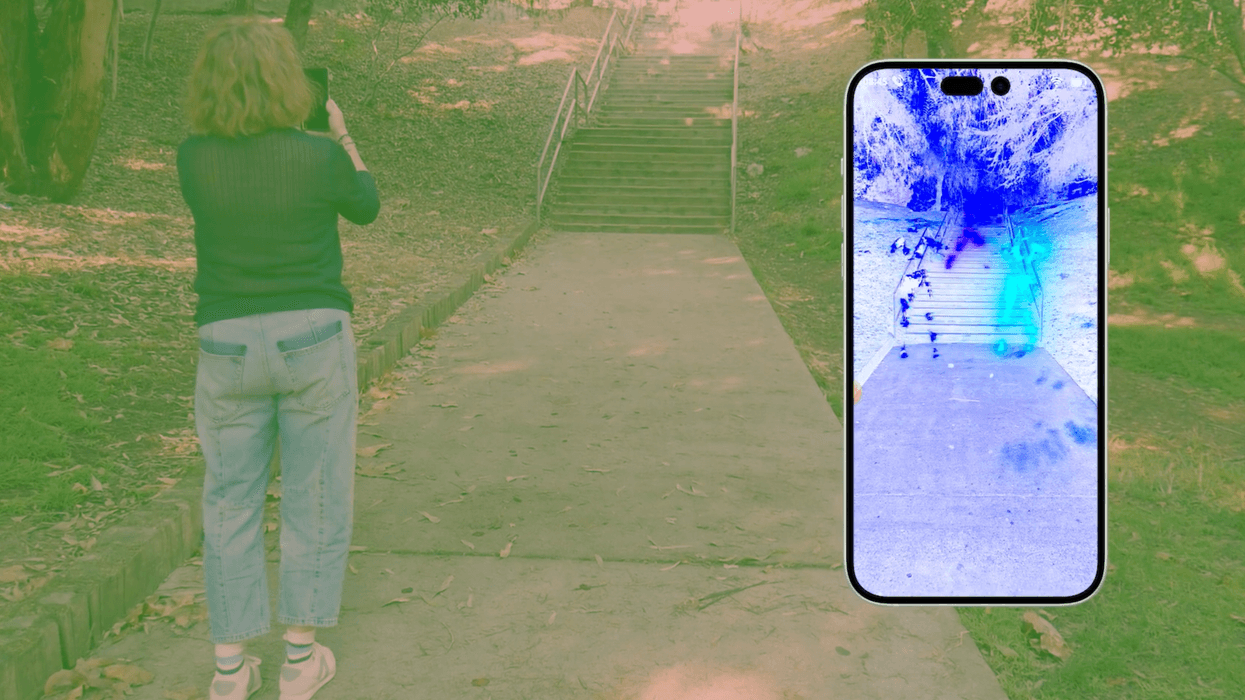

Top image: reopening after lockdown at Marwell Zoo

Saudi Arabia's AlUla

Saudi Arabia's AlUla

Immotion CEO Rod Findley and VP of Content Ken Musen celebrating their Lumiere win at the 16th Annual Lumiere Awards, held on 9 February at the iconic Beverly Hills Hotel.

Immotion CEO Rod Findley and VP of Content Ken Musen celebrating their Lumiere win at the 16th Annual Lumiere Awards, held on 9 February at the iconic Beverly Hills Hotel.