Prague has a new museum, and it’s all about the great Czech artist Alphonse Mucha.

The Mucha Museum has just opened its doors in the heart of Czechia’s historic capital, in a restored wing of the Savarin Palace complex which is undergoing massive redevelopment.

The museum is dedicated to the work and life of Mucha. He is one of the most prominent artists of the Art Nouveau movement, and his renown has waxed and waned in both life and death.

Celebrated as “the greatest decorative artist in the world” when he visited America in 1904, Mucha’s legacy is intertwined with the history of 20th century Europe. That his reputation — as well his canvases — survived both fascism and communism is a remarkable part of his story.

Today, Mucha is hailed in his homeland, and revered in Japan and Asia where his work has inspired Manga. But compared to his contemporaries, such as Monet, Van Gogh, and Gauguin, he enjoys less recognition than he deserves elsewhere.

[rebelmouse-image 61220116 expand=1 dam=1 alt="Portrait of Marcus Mucha, great-grandson of Alphonse Muchaand Executive Director of the Mucha Foundation, inside MuchaHouse in Prague. Photo: Jaroslav Fikota, © Mucha Trust 2024" site_id=26859892 is_animated_gif="false" original_size="1024x1379" crop_info="%7B%22image%22%3A%20%22https%3A//assets.rbl.ms/61220116/origin.jpg%22%2C%20%22thumbnails%22%3A%20%7B%22origin%22%3A%20%22https%3A//assets.rbl.ms/61220116/origin.jpg%22%2C%20%22210x%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D210%22%2C%20%22600x200%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D600%26height%3D200%26coordinates%3D0%252C519%252C0%252C519%22%2C%20%221000x750%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1000%26height%3D750%26coordinates%3D0%252C305%252C0%252C306%22%2C%20%221200x400%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1200%26height%3D400%26coordinates%3D0%252C519%252C0%252C519%22%2C%20%221200x600%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1200%26height%3D600%26coordinates%3D0%252C433%252C0%252C434%22%2C%20%22750x1000%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D750%26height%3D1000%26coordinates%3D0%252C7%252C0%252C7%22%2C%20%221245x700%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1245%26height%3D700%26coordinates%3D0%252C401%252C0%252C402%22%2C%20%222000x1500%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D2000%26height%3D1500%26coordinates%3D0%252C305%252C0%252C306%22%2C%20%22600x300%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D600%26height%3D300%26coordinates%3D0%252C433%252C0%252C434%22%2C%20%22600x%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D600%22%2C%20%22980x%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D980%22%2C%20%22300x300%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D300%26height%3D300%26coordinates%3D0%252C177%252C0%252C178%22%2C%20%2235x35%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D35%26height%3D35%22%2C%20%22700x1245%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D700%26height%3D1245%26coordinates%3D124%252C0%252C124%252C0%22%2C%20%22600x600%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D600%26height%3D600%26coordinates%3D0%252C177%252C0%252C178%22%2C%20%22300x%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D300%22%2C%20%221200x800%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1200%26height%3D800%26coordinates%3D0%252C348%252C0%252C349%22%2C%20%221500x2000%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1500%26height%3D2000%26coordinates%3D0%252C7%252C0%252C7%22%2C%20%22600x400%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNi9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4MzMyOTA0M30.twNSZr663mBzvSa_bCNIKSv0LDsc9vICdlZzs3OdHdE/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D600%26height%3D400%26coordinates%3D0%252C348%252C0%252C349%22%7D%2C%20%22manual_image_crops%22%3A%20%7B%229x16%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%22700x1245%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%200%2C%20%22height%22%3A%201379%2C%20%22width%22%3A%20776%2C%20%22left%22%3A%20124%7D%2C%20%22600x300%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%22600x300%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20433%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20512%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%223x1%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%221200x400%22%2C%20%22600x200%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20519%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20341%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%223x2%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%221200x800%22%2C%20%22600x400%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20348%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20682%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%221x1%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%22600x600%22%2C%20%22300x300%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20177%2C%20%22height%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%223x4%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%221500x2000%22%2C%20%22750x1000%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%207%2C%20%22height%22%3A%201365%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%2216x9%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%221245x700%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20401%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20576%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%224x3%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%222000x1500%22%2C%20%221000x750%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20305%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20768%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%222x1%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%221200x600%22%2C%20%22600x300%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20433%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20512%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%7D%7D" caption="Portrait of Marcus Mucha, great-grandson of Alphonse MuchaPortrait of Marcus Mucha, great-grandson of Alphonse Mucha and executive director of the Mucha Foundation, inside Mucha House in Prague. Photo: Jaroslav Fikota, © Mucha Trust 2024

and Executive Director of the Mucha Foundation, inside Mucha

House in Prague. Photo: Jaroslav Fikota, © Mucha Trust 2024" photo_credit="" title="foto-pro-john-mucha"]Portrait of Marcus Mucha, great-grandson of Alphonse Mucha

and Executive Director of the Mucha Foundation, inside Mucha

House in Prague. Photo: Jaroslav Fikota, © Mucha Trust 2024

“The Anglo Saxon or historical establishment hasn't caught up with the scholarship that we've been developing over the last 30 years,” Marcus Mucha, great-grandson of Alphonse and executive director of the Mucha Foundation, told me on a preview visit to the museum.

So the new venue and the Mucha Foundation running it aim to “keep knocking on that door” and reestablish Mucha to a broader international audience (Prague welcomes 8 million tourists a year). They want to ensure that stubborn misconceptions do not obscure his legacy.

Mucha and Art Nouveau

One of those misconceptions is that Mucha was ‘just a poster artist.’

[rebelmouse-image 61220117 expand=1 dam=1 alt="Alphonse Mucha - Self portrait Prague - c 1937 © Mucha Trust 2024" site_id=26859892 is_animated_gif="false" original_size="1024x1380" crop_info="%7B%22image%22%3A%20%22https%3A//assets.rbl.ms/61220117/origin.jpg%22%2C%20%22thumbnails%22%3A%20%7B%22origin%22%3A%20%22https%3A//assets.rbl.ms/61220117/origin.jpg%22%2C%20%221200x800%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1200%26height%3D800%26coordinates%3D0%252C349%252C0%252C349%22%2C%20%221000x750%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1000%26height%3D750%26coordinates%3D0%252C306%252C0%252C306%22%2C%20%22750x1000%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D750%26height%3D1000%26coordinates%3D0%252C7%252C0%252C8%22%2C%20%22600x200%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D600%26height%3D200%26coordinates%3D0%252C519%252C0%252C520%22%2C%20%22600x400%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D600%26height%3D400%26coordinates%3D0%252C349%252C0%252C349%22%2C%20%2235x35%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D35%26height%3D35%22%2C%20%22600x300%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D600%26height%3D300%26coordinates%3D0%252C434%252C0%252C434%22%2C%20%22210x%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D210%22%2C%20%22600x600%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D600%26height%3D600%26coordinates%3D0%252C178%252C0%252C178%22%2C%20%22980x%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D980%22%2C%20%221245x700%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1245%26height%3D700%26coordinates%3D0%252C402%252C0%252C402%22%2C%20%222000x1500%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D2000%26height%3D1500%26coordinates%3D0%252C306%252C0%252C306%22%2C%20%221200x600%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1200%26height%3D600%26coordinates%3D0%252C434%252C0%252C434%22%2C%20%221200x400%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1200%26height%3D400%26coordinates%3D0%252C519%252C0%252C520%22%2C%20%22300x%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D300%22%2C%20%22300x300%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D300%26height%3D300%26coordinates%3D0%252C178%252C0%252C178%22%2C%20%22600x%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D600%22%2C%20%22700x1245%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D700%26height%3D1245%26coordinates%3D123%252C0%252C124%252C0%22%2C%20%221500x2000%22%3A%20%22https%3A//blooloop.com/media-library/eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpbWFnZSI6Imh0dHBzOi8vYXNzZXRzLnJibC5tcy82MTIyMDExNy9vcmlnaW4uanBnIiwiZXhwaXJlc19hdCI6MTc4NDk1Mzk4MH0.D_lHM3HUjHWNjjhIU6tR5UKgtCYuVkNmpLts_ZHz1Eo/image.jpg%3Fwidth%3D1500%26height%3D2000%26coordinates%3D0%252C7%252C0%252C8%22%7D%2C%20%22manual_image_crops%22%3A%20%7B%229x16%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%22700x1245%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%200%2C%20%22height%22%3A%201380%2C%20%22width%22%3A%20777%2C%20%22left%22%3A%20123%7D%2C%20%22600x300%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%22600x300%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20434%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20512%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%223x1%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%221200x400%22%2C%20%22600x200%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20519%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20341%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%223x2%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%221200x800%22%2C%20%22600x400%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20349%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20682%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%221x1%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%22600x600%22%2C%20%22300x300%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20178%2C%20%22height%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%223x4%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%221500x2000%22%2C%20%22750x1000%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%207%2C%20%22height%22%3A%201365%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%2216x9%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%221245x700%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20402%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20576%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%224x3%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%222000x1500%22%2C%20%221000x750%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20306%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20768%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%2C%20%222x1%22%3A%20%7B%22sizes%22%3A%20%5B%221200x600%22%2C%20%22600x300%22%5D%2C%20%22top%22%3A%20434%2C%20%22height%22%3A%20512%2C%20%22width%22%3A%201024%2C%20%22left%22%3A%200%7D%7D%7D" caption="Alphonse Mucha, Self portrait, Prague, c.1937, © Mucha TrustAlphonse Mucha, Self portrait, Prague, c.1937, © Mucha Trust 2024

2024" photo_credit="" title="alphonse-mucha-self-portrait-prague-c-1937-mucha-trust-2024"]Alphonse Mucha, Self portrait, Prague, c.1937, © Mucha Trust

2024

He is indeed most famous for his pioneering work with posters. He rose to fame in Paris in the 1890s when his lithograph posters for Sarah Bernhardt, the most celebrated French actress of the day, became immediately iconic. Their sinuous lines, organic forms and muted palette became synonymous with the newly emerging Art Nouveau decorative style of the time. The streets of Paris became “open-air art exhibitions” and made “Le Style Mucha” famous worldwide.

It’s unsurprising then that posters feature heavily in the new museum. Marcus believes they are showing visitors “the best preserved ensembles of those posters that are just as fresh and just as colorful as they were on the streets of Paris in the 1900s.”

But there’s an attempt to go beyond this medium. The museum emphasises how Mucha was a versatile artist who turned his hand to painting, sculpture, photography and design. He was also an inspiring teacher and philosopher. An avowed “artist for the people”, for Mucha art was a language to express his ideal of drawing people together to promote progress and peace.

The museum features a permanent exhibition called Alphonse Mucha: Art Nouveau & Utopia. Here, some 90 works are on show, including paintings, posters, drawings, books and photographs, along with video.

The exhibition has a modest footprint of three galleries. This definitely isn’t like near-namesake Edvard Munch and his 13-storey museum in Oslo for example. But size isn’t everything, and it manages an illuminating journey exploring Mucha’s artistic and spiritual evolution from those famous Art Nouveau posters, through to the story of the creation of his masterpiece, The Slav Epic.

Mucha’s Slav Epic

The third and final gallery focuses on the epic — Mucha’s monumental painting series.

He began these works after his return to his homeland in 1910. He had secured sponsorship from an American industrialist, so he could fulfill a long-held ambition to create a series dedicated to his fellow Slavs.

What he produced was an expansive and large-scale series of 20 paintings (some over 6 x 8 metres) depicting key moments in Slavic history, mythology, and culture. They range from the Slavic civilisation’s origins in ancient times, through the Middle Ages and the Religious Reformation, to the aftermath of the First World War. Throughout the cycle, he celebrated the unity and spirit of the Slavic people.

In the Mucha Museum, four scaled-down reproductions represent the epic. These will rotate over time (the opening four are the first four in the series). It also features Mucha’s preparatory photographs of models for the compositions, and some text and video.

Reproductions feature here because the canvases are some 200km away in the Moravský Krumlov castle, near the Czech city of Brno. In 1929 the series was gifted to the City of Prague. However, the donation came with the condition that authorities build a dedicated exhibition space for it. That never happened.

Leaving a legacy

Following Mucha’s death in 1939, shortly after being interrogated by the Gestapo (Mucha was one of the first people the Nazi’s arrested after their invasion of Czechoslovakia), the epic was suppressed for decades due its representation of a strong Slavic population. The canvases were hidden and neglected, first by the Nazis, and later by the communist rulers.

Remarkably though, they weren’t destroyed, and they were put on display in the Moravský Krumlov castle in 1963 during a thawing of communist suppression of culture. They have largely remained there to this day.

But in 2010, when the crumbling Krumlov castle had to shut for vital repairs, a fierce legal battle erupted over where the rightful home for the epic should be.

The Mucha family and the City of Prague both wanted them back in the capital as Alphonse originally stipulated. However, the two parties could not agree on rightful ownership or a suitable location. The dispute played out extensively in the press and even made it to the Supreme Court.

A breakthrough was seemingly reached in 2023, when the two sides agreed to co-operate in creating a centre where the epic can be displayed. It included reference to the location being a huge new gallery built underground at the Savarin Palace, with the help of the project’s developer Crestyl. However, two years later, the plans are still not final. Further negotiations are ongoing.

A new space

At the museum’s opening press conference, Marcus Mucha was confident it would go ahead at the Palace — as a separate, but complimentary space to the new museum.

“In cooperation with the City of Prague, we will be taking some space from Crestyl, to show the Slav Epic in a bespoke, newly designed space that Thomas Heatherwick is going to design for us.”

He said he was thrilled to have the prolific British designer involved, as “growing up [Heatherwick] was inspired by Alphonse Mucha.”

But in a nod to the ongoing uncertainty over the project, Marcus acknowledged “we don't know quite what it's going to be.”

“My personal dream” he said, “is that Alphonse gave the Slav Epic to the city of Prague in 1928, so if we could commemorate the centenary in 2028 with the opening of [Heatherwick’s] space… well, our family's been waiting for a party like that for 100 years.”

The Mucha Museum at Prague’s Savarin Palace

Whether Heatherwick’s vast underground gallery ever comes to fruition, the Savarin Palace project will transform a significant chunk of historic Prague.

The Mucha Museum is the first space open in the newly-restored Palace. This is a Baroque landmark that dates back to the 18th century. But the regeneration project Crestyl embarks on here is much larger, going beyond the historic building and encompassing an entire city block bordered by four of Prague’s busiest shopping streets.

In the future, there will be new office, retail and commercial spaces, as well as a new public square, courtyard and walkways, and possibly even a new connection to the city’s metro in the basement. It’s all being overseen by Heatherwick.

It’s “going to change the face of Prague” Crestyl’s CEO, Simon Johnson told me. He emphasises the location’s prestige by comparing it to London. “Just imagine a 1.7 hectare site on the corner of Oxford Street and Bond Street…it’s extraordinary.”

The palace's restoration was completed with the museum's opening. “It's a beautiful building, and it was in a terrible condition,” Johnson says of the new galleries. These are on the first floor and until recently were a casino. He tells me that Crestyl owns the building (purchased about eight years ago). It has leased the exhibition space for 10 years to the Mucha Foundation.

The lease is not free of charge, but Johnson points out that being on the first floor is a much more affordable option. The ground floor units — onto those busy Prague shopping streets — are prime real estate. New commercial tenants will be revealed later this year.

Altogether, the Savarin Palace restoration has cost nearly €25m while the entire Savarin project will exceed €400m. Once construction begins, they hope it will take three years.

Touring exhibitions globally

While the Mucha Foundation waits to see if the Slav Epic does manage to come to Prague, its focus over the coming years will not just be on this new museum but on touring new exhibitions around the world, to continue their mission to reconnect mass global audiences with Mucha’s output.

The biggest of these shows is a major US touring exhibition, Timeless Mucha: The Magic of Line. This has just opened at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. It will travel across the United States through to 2026. In March 2025, an exhibition dedicated to Mucha will open at the Palazzo des Diamanti in Ferrara, Italy.

At the much anticipated Expo 2025 in Osaka, Mucha will be representing the Czech Republic. And there’s also a long-term collaboration between the Mucha Foundation and Google.

Marcus believes holding a Mucha exhibition is a no-brainer for international museums and galleries based on the evidence of previous touring shows. “Museums around the world tend to find that when they do a Mucha exhibition, they break their visitor records,” he told me.

“We were really happy in 2018 and 2019 when we did a show at the Museum de Luxembourg in Paris.” The exhibition — which was conceived and curated by Mucha Foundation curator Tomoko Sato, who has done the same role in the new Prague museum — drew 342,000 visitors.

“It was the second most attended exhibition ever in the history of the Musee de Luxembourg. So Cezanne was number one, Mucha was number two, and then Chagall was number three. It was very nice to be able to do that.”

Mucha Sekt and Mucha licensing

But the touring shows are not just about boosting visibility for Mucha outside Czechia. They are also vital sources of income.

“We're a private foundation, we don't get any subsidies or European money or municipal support from Prague. So we rely entirely on earned income to take care of the collection, to employ our team.” It’s these exhibitions, Marcus told me, that support these activities.

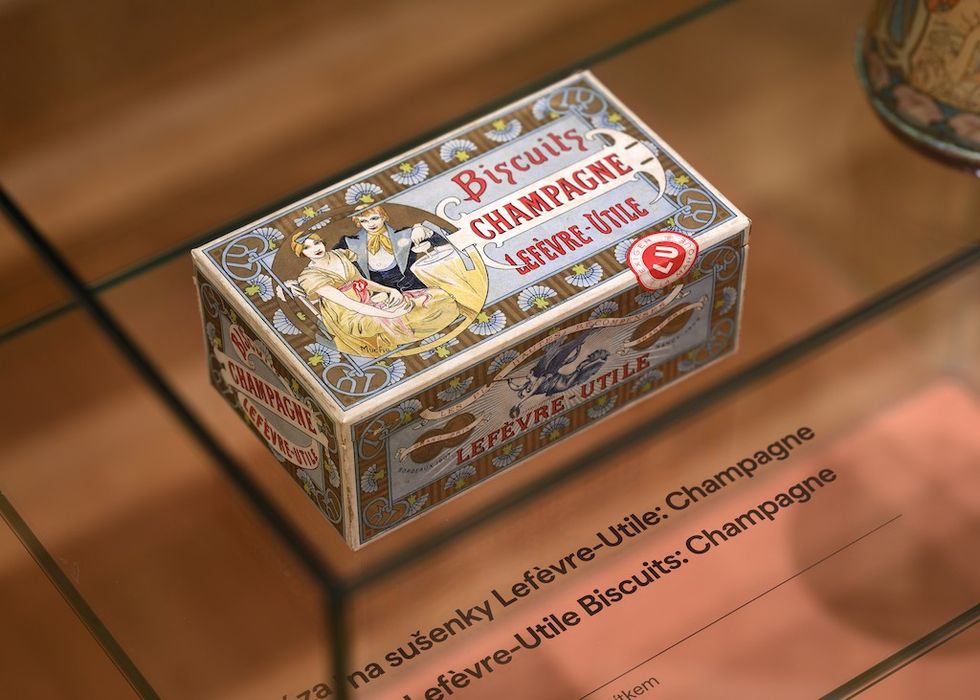

Another revenue strand is licensing; a prominent example was very visible at the opening.

Guests were treated to flowing Mucha Sekt, a range of sparkling wines by Czech producers Soare Sekt under license from the Mucha Foundation. And it’s a natural partnership, as Mucha himself worked on advertising for the Moët & Chandon champagne house.

Mucha Sekt has a range of ten products created from grapes from across the European Union, brand manager Barbara Kozielová told me. Two more lines are due soon. She says that each bottle is paired with a Mucha artwork. They’re proud that the range regularly wins industry awards.

It’s a successful partnership. The brand is found in supermarkets all over the country and enjoys the second largest market share. According to Marcus, it’s one of the license agreements that make up the Mucha Foundation’s “diversified range” of income streams.

What next for the Mucha Foundation?

With Mucha firmly recognised as a hero in his homeland, record breaking shows in Paris, and a new touring show in the USA (not to mention regular exhibitions in Japan), where’s next to reaffirm “Le Style Mucha”?

Could it be Britain, I ask? Marcus says a touring show went to four venues in 2015. However, he adds that London hasn’t seen a major Mucha exhibition for over thirty years.

“London is really due one — and we'd be thrilled. A lot of the idiom of the swinging 60s in London was inspired by Mucha’s art,” he says.

But he also thinks it’s in the interests of London’s museum to take a Mucha show. He firmly believes it makes good business sense.

“It will help some of those London museums combat the visitor shortfalls that haven't quite come back since COVID. One way that London museums could do well to help their budgets is to put on a Mucha exhibition.”

Image credit Tilly Buckroyd

Image credit Tilly Buckroyd The frontage of Sir John Soane's Museum, including no. 12 - 14 Lincoln's Inn FieldsImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum

The frontage of Sir John Soane's Museum, including no. 12 - 14 Lincoln's Inn FieldsImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum The bust of Sir John Soane, by the sculptor Francis Chantrey Image credit John Stead, © Sir John Soane’s Museum

The bust of Sir John Soane, by the sculptor Francis Chantrey Image credit John Stead, © Sir John Soane’s Museum  The fireplace in the Library-Dining Room at no. 13 Lincoln's Inn Fields, part of Sir John Soane's MuseumImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum

The fireplace in the Library-Dining Room at no. 13 Lincoln's Inn Fields, part of Sir John Soane's MuseumImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum The Model Room at Sir John Soane's MuseumImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum

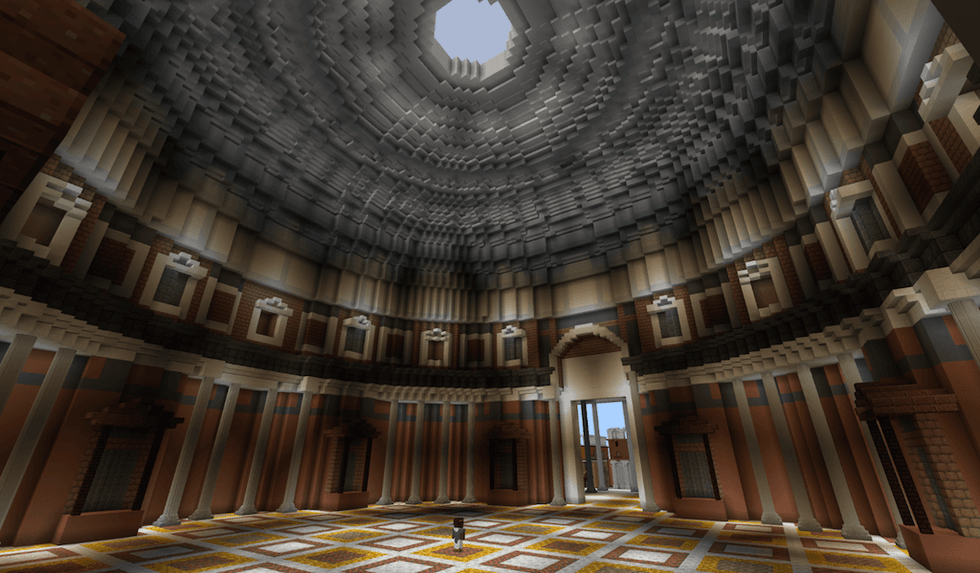

The Model Room at Sir John Soane's MuseumImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum Screenshot from Soane's Portals to the Past

Screenshot from Soane's Portals to the Past

Sir John Soane's breakfast room at no. 13 Lincoln's Inn FieldsImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum

Sir John Soane's breakfast room at no. 13 Lincoln's Inn FieldsImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum Sir John Soane's Drawing OfficeImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum

Sir John Soane's Drawing OfficeImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum The Dome, at Sir John Soane's MuseumImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum

The Dome, at Sir John Soane's MuseumImage credit Gareth Gardner, © Sir John Soane’s Museum

Centre for Contemporary Arts in Tashkent (CCA) View of the lower lobby. Render C Studio KO. Courtesy of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF)

Centre for Contemporary Arts in Tashkent (CCA) View of the lower lobby. Render C Studio KO. Courtesy of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF)

Image © Niall Hodson

Image © Niall Hodson

Image courtesy of NHS

Image courtesy of NHS Image courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects

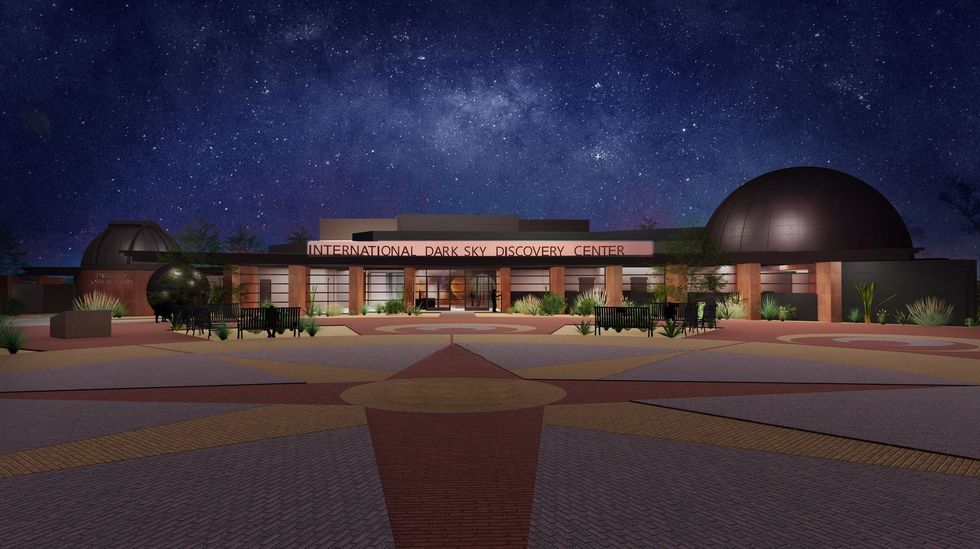

Image courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects  Image courtesy of IDSDC

Image courtesy of IDSDC Image courtesy of Herzog & de Meuron

Image courtesy of Herzog & de Meuron

Image courtesy of the New York Historical

Image courtesy of the New York Historical

Image courtesy of Marvel.

Image courtesy of Marvel.

Image courtesy of Secchi Smith

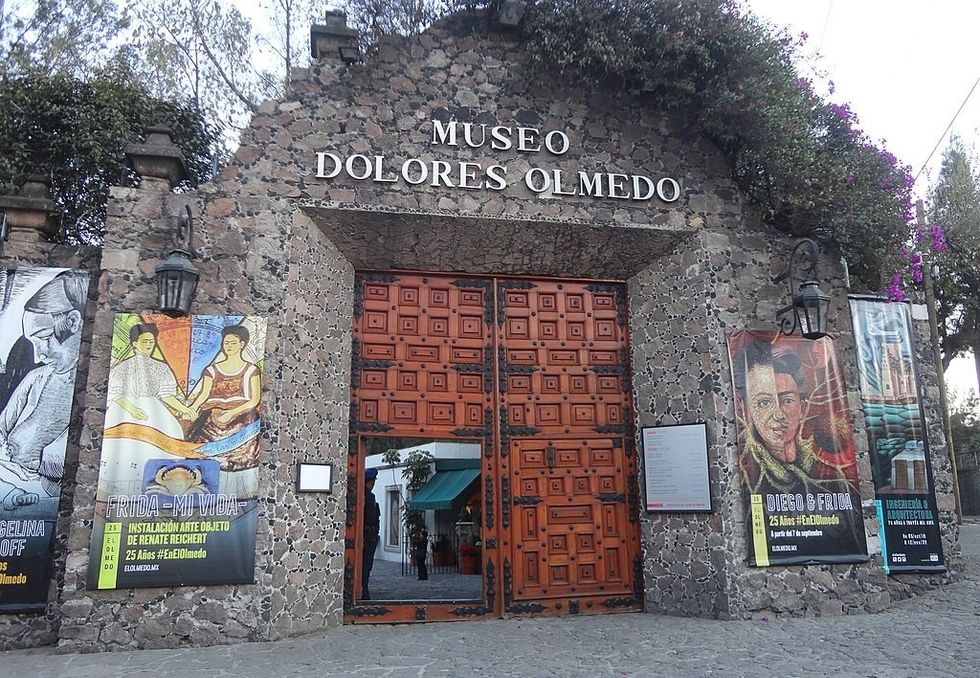

Image courtesy of Secchi Smith  Juan Carlos Fonseca Mata, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Juan Carlos Fonseca Mata, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons