The Ad Gefrin Anglo-Saxon Museum and Whisky Distillery in Wooler, Northumberland, opened on 25 March 2023

One of the 20th century’s most remarkable Anglo-Saxon archaeological finds, The Great Hall of Ad Gefrin at Yeavering in Northumberland, was discovered almost accidentally by an archaeology professor taking aerial photographs in 1949.

70 years after the remains were first uncovered, they have been brought alive in a project that recreates the palace’s Great Hall. A dedicated visitor centre and Anglo-Saxon Museum in nearby Wooler tells the untold story of the 7th-century royal court, home of Aethelfrith, Edwin and Aethelburga, the saintly King Oswald, and his younger brother Oswy.

For over a century, these Anglo-Saxon kings and queens played an important role in the development of the later kingdom of Northumbria and the conversion to Christianity in the north of England.

The new centre is a partnership between the Gefrin Trust, which manages the archaeological site, and the local Ferguson family, who support the project through investment and the presence of their whisky distillery at the visitor centre. A range of contemporary crafts, arts and produce of the region is also on offer.

The Ad Gefrin vision

Dr Chris Ferguson, director of visitor experience at Ad Gefrin, talks to blooloop about the vision behind the project.

It is the brainchild of Alan and Eileen Ferguson, supported by the whole of the Ferguson family, an amalgamation of the local Redpath and Ferguson lineages. These have been part of the fabric of Northumberland as a major family-run business for almost 100 years. The site was originally owned by Eileen’s family and operated as Redpath Bros. Haulage from the 1920s until 1998.

“I didn’t go into that side of the business; I’m an archaeologist, a museum and culture professional,” says Dr Ferguson.

“When I came back to work with the family, we decided to create something that was a visitor attraction destination with the distillery. We wanted to do something cultural that celebrated the area and our Anglo-Saxon heritage and story, and that also created jobs locally. The idea with the whisky distillery was to make something using Northumbrian barley. This is mainly used for the malt whisky industry anyway.”

Discovering Yeavering

Yeavering, the royal palace at Ad Gefrin, is still the best-understood royal palace complex from that era. Another famous Anglo-Saxon find, the Sutton Hoo royal ship burial in Suffolk was discovered in 1939. Being a ship burial, it had helmets, shields, burial assemblage and so on. Yeavering was discovered in 1949 from aerial photography that developed from wartime reconnaissance.

“Brian Hope-Taylor spent more than 10 years excavating there and found all the evidence of the great hall. All he got archaeologically, given the nature of the site, however, was a whole load of timber remains. He found the footings of buildings and so on, rather than grave goods.”

There simply isn’t the quantity of material from the royal palace as was found at the Sutton Hoo burial:

“For all that it’s just as important as Sutton Hoo.”

Reimaging the Great Hall at Ad Gefrin

Ad Gefrin did get a lot of attention in the 1950s and 60s:

“There was a TV series,” Ferguson says. “It was a brilliant piece, in its day, but it dropped out of popular consciousness, except among archaeologists. If you do an archaeological degree on this period, Yeavering is the first site you talk about. It’s fundamental, but beyond that world, in the public mind, it just hasn’t had its press coverage in recent years.”

Until now.

“The idea is to create a museum that reimagines the interior of the Great Hall,” he explains:

“You meet the characters. One of the best things about Yeavering, one of the things that made the publication of Brian Hope-Taylor’s excavations a masterpiece, is the overlap between archaeology and history.”

“We know about the people from Bede and evangelical history. We know about the people who lived there. So, we can tell the stories and bring them to life in a way that other archaeological sites from that period would struggle with. Because we know exactly which king, which queen, which court, and who these people were. We have their names. We know enough about them to create something really fun where people can actually feel they have met them.”

The era of Beowolf

This is the period that Anglo-Saxon poetry immortalised. It is the time of Beowulf, the Wanderer, the Seafarer, the Battle of Maldon, and the Dream of the Rood:

“We have a section on the Dream of the Rood,” Ferguson explains. “We also touch on the Seafarer and the Wanderer: this is where the literature, the history and the archaeology collide. All those great descriptions of the hero in Beowulf took place inside a Great Hall in the 7th century, and then this is what that looked like.

“This is the world you’re walking into: it is the world that Beowulf is telling you about.”

The Great Hall is brought to life as an immersive experience. There is a consciousness of colour, and the way people move through the space.

“After the Great Hall, we have a museum where we look through the Golden Age of Northumbria,” he explains. Northumbria’s Golden Age was a period from the beginning of the 7th to the end of the 8th century AD. Art, culture, and learning flourished:

“One of the famous objects from that Golden Age is the Ruthwell Cross. This is part of the tradition of Northumbrian stone carving.”

The Ruthwell Cross and the Dream of the Rood

The Ruthwell Cross, created in the early 700s, a time when the kings of Northumbria extended their rule into southwest Scotland, had a very narrow escape in around 1642. At this time, it was named in a Church of Scotland Act against ‘idolatrous monuments’.

“A local minister destroyed it in what appears to have been reluctant acquiescence. The fragments were reused as church seating or buried in the graveyard. Between 1802 and 1823 the cross was painstakingly reconstructed, with a new head carved by a local mason. In 1887 it was returned to a purpose-built apse at the kirk, where it remains.”

The Dream of the Rood is carved into one of the cross’s sides, among swirling vines. Once misidentified as Norse runes, it was deciphered in 1840.

“We have a scaled-down replica of the Ruthwell cross in our room of Ruthwell. Here, we unpack the Dream of the Rood for visitors, taking them through this amazing piece of poetry that tells us about the crucifixion from the perspective of the Cross.”

Ad Gefrin connects visitors with Northumbria’s past

He explains how different forms of interpretation throughout the museum connect visitors with the stories and people of Northumbria’s past:

“One of the things we are trying to do is not make this just a story of royal palaces and kings. This is about people: it’s the story of everyone in the Great Hall. These places only worked with the totality of the community. It’s not just about a king.”

“From an interpretive approach, we’re trying to take visitors on an immersive journey. They walk from our reimagining of the Great Hall, and on into the museum space itself. It’s not the Ashmolean; it’s not simply lots and lots of objects. It’s more about setting objects into a thematic context through which we explore the site.

“We look at how it’s a place of creativity, of power, of faith in the Christian story and also the Pagan story. We look at the discovery and loss of the site. Also, we also look at landscape and language. We have all these strands of themes and then there is the distillery story.

“It’s not like any other whisky distillery tour that you’re likely to go on. You take those strands of theming with you to explore the whisky story and the Northumbrian story, and how that informs 21st-century Northumbria from the 7th-century Golden Age. The threads tie it all altogether.”

Whisky at Ad Gefrin

The whisky distillery itself is one of those threads:

“We wanted to do something that is at the heart of it,” he explains. “We wanted to celebrate our local history and culture, and celebrate it now as well as then. This is something you could only find in North Northumberland. You couldn’t create this somewhere else.”

The museum and the whisky distillery both have a focus on hospitality and cultural exchange.

“That is something that we see, again, in Beowulf. Yeavering is that place of hospitality, that place of assembly, that place of gathering.”

Touching on the theatrical qualities of the Yeavering hall, he adds:

“Yeavering is unique in that not only has it a Great Hall, but it has a timber grandstand, like a timber pie-wedge of a Roman amphitheatre, with a throne or a seat: a stage. All the first conversions to Christianity, all the things like that, would have happened in that space.”

A sense of hospitality

We know from sources like Beowulf how such a space would have operated. He explains:

“The Queen would go around, offering the mead cup. Northumberland was, and is, known for its hospitality. People from the North East are just a friendly bunch. That’s something we wanted to build on and bring into the everyday. When people come to visit us, we are a modern place of hospitality in that same sense of warmth and welcome: come, sit by the fire and make yourself at home.

“We’re not a hospitality venue in the way that commercial hospitality venues talk about it, but in the old sense; the true meaning of the word.”

The Gefrin Trust

He outlines the project’s partnerships:

“All of this is done in partnership with the Gefrin Trust. They are the guardians of the archaeological site itself and have lent us the material for the displays from the Brian Hope-Taylor archive. We also have artefacts from the British Museum, the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, and so forth that add context.

“We have done a lot of work with the Gefrin Trust and Northumberland National Park about how we then do education programming in the future, looking at how that works in terms of connecting it to the community. The plan is to do lots of events and outreach as the years go by.”

The target market is broad comprising locals, and both domestic and overseas tourists:

“We do want people to love us locally,” Ferguson explains. “We want to be the place that local people take great pride in, so that they want to come back. There is an annual pass, which assures a discount in the shop and unlimited trips through the museum, as well as a discount in the bistro.

“We want to be loved by people locally and regionally; to have a loyal base.”

Reaching a wide range of visitors

The attraction is also on the tourist trail:

“We want to be one of the key places to go if you want to learn about the early mediaeval or the Saxon period of Northumbria,” he says:

“We tell the story of the royal court. Nobody else does that up here. You can go to Lindisfarne, you can go to Durham, you can go to Jarrow, Hartlepool, Whitby, and get that monastic religious story. We are the period that leads up to that. You can’t have those monasteries without the context of the Royal Court, so that’s how we fit in. A trail of Anglo-Saxon Northumbria would begin with us as the jumping-off point to go on to the National Park.”

And, of course, he adds:

“We are also here for the drive-by tourists who have an interested in the whisky side of things, going up to Scotland to do the whisky trails: we are part of the Borders whisky trail.”

Local produce at Ad Gefrin

As well as its whisky, the museum sells local arts, crafts and produce. Ferguson adds:

“It’s not as if the whisky distillery and the Anglo-Saxon museum sit far apart. They are tied. You can only do the distillery tour having done the museum.”

The spirit products all take their names and their story from this period of Anglo-Saxon history.

“Our first whisky blend is Tácnbora. This means ‘standard bearer’ in old English.”

King Edwin was always preceded by a standard bearer carrying the effigy of a goat’s head (now central to Ad Gefrin’s brand marque):

“King Edwin’s standard bearer was buried at Yeavering; the story of his burial was described by Bede. We have Edwin’s standard, which was found at Yeavering. We realised that, for our first whisky product, this is the story for us. This whisky is our standard, our first thing to go out into the world.

“The idea is that all our spirits, wherever they go in the world over the years to come, will be carrying these stories with them.”

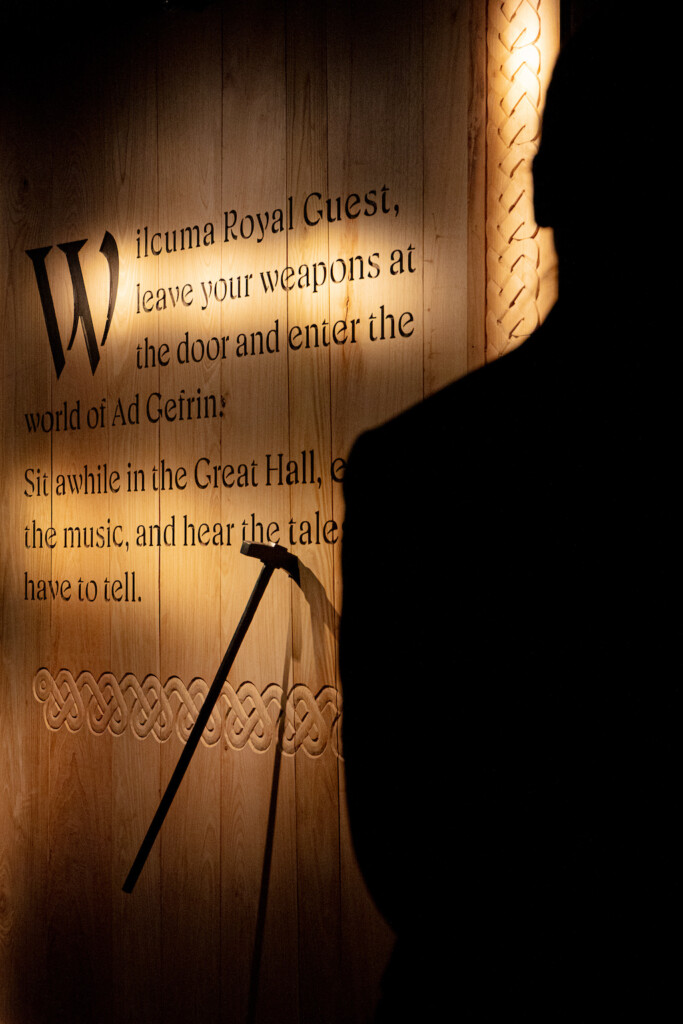

Top image: the Atrium at Ad Gefrin Anglo-Saxon Museum and Distillery, credit Sally Ann Norman