Leading multi-sensory experience design studio Bompas & Parr is collaborating with Historic England and Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) to create an immersive museum dedicated to William Shakespeare.

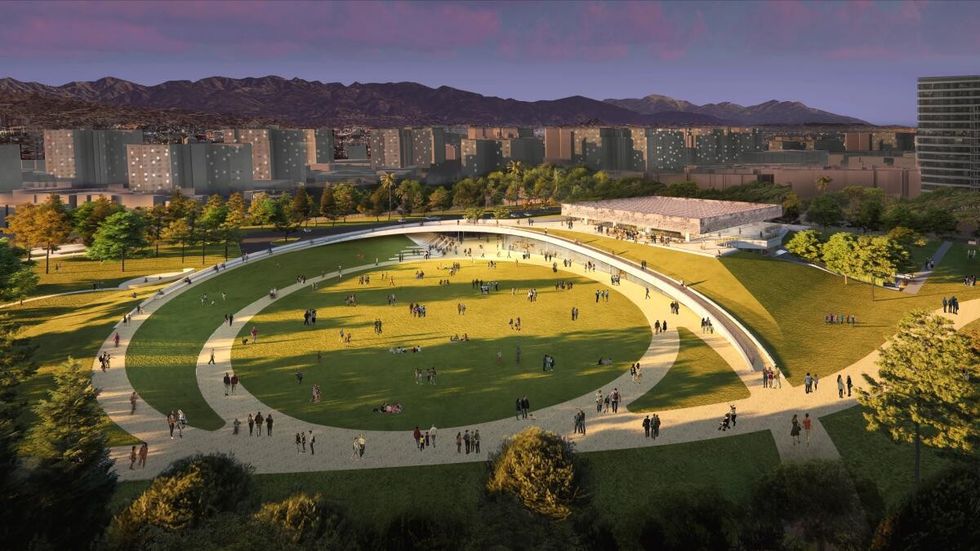

Opening in 2024, London’s new Museum of Shakespeare is being built on the site of the Curtain Theatre in Shoreditch, the main venue for Shakespeare's company before the Globe was built. The site was first uncovered by archaeologists in 2011. The new museum will include a projected reconstruction of the original theatre above the remains of the stage. It will, using AI, bring the world of London in 1598 to life.

Visitors, ‘transported’ through Bompas and Parr’s wizardry to the 16th century, will also be able to perform on the stage where Romeo and Julie t and Henry V debuted.

“The Museum of Shakespeare will be the most ambitious project that Bompas & Parr has undertaken. It is in line with our mission to create location-based experiences that make London a more interesting place and a city unrivalled in its cultural importance,” said Bompas & Parr co-founder Harry Parr.

Heather Knight, senior archaeologist at MOLA, and Sam Bompas of Bompas and Parr speak to blooloop about the project.

A passion for archaeology

For Knight, archaeology is a lifelong passion.

“From the age of about six, I knew this is what I wanted to do,” she tells blooloop.

This project is special:

“Leading the excavations on the site of the Curtain has been a privilege. Shakespeare still has a worldwide connection with people. With that comes an enormous responsibility, because obviously, with archaeology, you only get one chance to get it right. It's a two-edged sword: an enormous privilege, but also an enormous responsibility.”

She outlines the project, which has transformed our understanding of early modern performance, from the beginning:

“In 2011, we did some trial trenches on the site, as part of a feasibility study, to see if the site could be developed. On one of the buildings was a brown plaque that said ‘This is the site of the Curtain Theatre’. The then-client wanted to know if it really was, and, if so, whether any remains survived. The first trial trenches we dug on the site were down the back of the Horse and Groom pub.”

Within the first trench dug, the team found walls and surfaces that seemed promising:

“They were the right age and doing the right thing for them to be - possibly - part of the Curtain Theatre.”

Finding the Curtain Theatre

That then led to more trial excavation:

“We did a full open area excavation in that area, on that road frontage to try and find the full extent of the building. It was at that point we realised the building was the right date, and had finds associated with it that you'd expect to find in a place of commercial entertainment. In 2016, we had enough information to be able to say, ‘Yes, we are fairly confident that this is the Curtain.’"

What they found confounded long-held assumptions about Tudor playhouses. She explains:

“What was, at that point, revolutionary was the fact that the building was rectangular. It's not one of the polygonal structures like the modern Globe, for instance.

"It was really interesting. Professor Holger Syme from Toronto wrote a blog in May 2016, in which he described it as a game-changing moment. It completely made us reevaluate what we thought we knew about playhouses and the evolution of drama and performance during that period.”

Excavating the site for the new Museum of Shakespeare

As it transpires, she explains:

“It’s actually more typical than those polygonal playhouses that we associate with Shakespeare. If you look at the playhouses in London in, say, around 1600, there are three that are polygonal, down on Bankside: the Rose, the Hope and the Swan. Yet around the suburbs to the north of the city, you have the Fortune, the Red Bull and the Curtain, all rectangular structures.

"We seem, then, to have something odd going on at this point. We had rectangular structures north and to the east of the city - there's the Red Lion down in Mile End as well - and then we had these polygonal structures, which everybody has come to regard as typical playhouses, purely on Bankside.

"It's making us reevaluate what we know, and that's never a bad thing.”

MOLA has excavated numerous playhouses over the years:

“We have dug the site of the Rose on Bankside, a tiny part of the original Globe, the Boar’s Head, and the Curtain. Another company has looked at the Red Lion at Mile End. Of all these playhouse sites, the Curtain is the best-preserved. Its walls stand, in places, to around a metre high. It has external surfaces that the audience stood on outside the playhouse. Fragments of the internal gravel surface that the audience stood on to watch performances are intact.

"We can see there were two rooms to the side of the stage. One of those has a rather nice cobbled floor to it. We then have steps down into that under-stage space. From the post holes and beam slots within that under-stage space, we can understand the framing that actually supported the stage.”

Museum to showcase archaeology

The Curtain is incredibly well preserved, she adds, because of the way it ended its life:

“The theatre was demolished in 1598. Of all the playhouses that we’ve done – around seven – it is the best-preserved. With other sites, we only have ground level and below remains. With the Curtain, we’ve only got three-quarters of the building. A quarter of it still probably exists under the Horse and Groom pub.

"But the fact that we have above-ground-level remains means we have enough to start to understand its architecture and to understand how people would have used that space.”

In terms of how the archaeology will be incorporated into the new Museum of Shakespeare, Knight comments:

“It’s now a scheduled monument. That is the highest level of protection the government can confer, because of its importance and rarity. The museum space wraps itself around the archaeology.

"There are plans to construct a glass stage at the original stage height over the remains. So, you'll be able to stand in the same space that Shakespeare stood. It's going to be the only playhouse that is truly accessible because all the others have been reburied. These will be the only physical remains that you'll be able to see and walk around, and stand on – or, at least, stand on the glass above. It will be… There isn’t a word. It’s going to be quite a thing.”

Discoveries challenge existing ideas

Turning to the artefacts discovered in the course of the excavation of the Museum of Shakespeare site, she says:

“We have dug a lot of the entire site, not just the area around the playhouse. From the entire site, finds-wise, we have something like 20,000 fragments of pottery and a similar amount of animal bone. Not all of those, obviously, relate to the late 16th, or early 17th centuries."

"The finds that we have that relate to the playhouse are things like beads from people's clothing – the type of tiny beads that might have been sewn onto a nice pair of gloves. We have fragments of beer mugs, and of the money pots that were used, possibly, by people selling food and drink within the playhouse.

"Tradition says they were used to collect money at the door. But another thing we're starting to re-evaluate is the use of money pots within these buildings. Rather than being used to collect money at the door, I think they're more likely to have been used by traders, folks selling food and drink within that space.

"Then there are tiny personal objects - bone combs, little dice. This gives us an idea of it as a place of people spending their leisure time. They're having a good time. It's the place to meet their friends, for drinking and gambling, as well as watching a play.”

A playhouse for everyone

The narrative for the Curtain, she explains, has always been that it was a comparatively down-market venue:

“According to contemporary accounts, it was a sort of citizens playhouse; a gentleman wouldn’t have been seen there. But when you look at the quantity of beads, for instance, that have come detached from high-end-ish clothing when jostled past each other, you think, ‘Well, hang on a minute. This is actually not necessarily the playhouse of the rabble. It’s probably the playhouse of the middle classes, too.’"

"There was a rise in the middle class at this point. They had money to spend watching a play, or fencing, or on other entertainment.”

The Curtain was one of London's fencing venues:

“So is that the reason for its bad reputation as a down-market venue?” Knight suggests. “Not through the audience, but through the performance and spectacle that people are going to see. I always liken it to cinema; it’s more of a Kill Bill venue than a Bridget Jones one. It might not have put on a rom-com, but it would have put on plays with fight scenes.

"The audience would have known what they were going to see. They would see comedy as well, but they would also be there to watch a company of actors who really know how to use a sword.”

Bompas & Parr to work on Museum of Shakespeare

Knight welcomes Bompas and Parr ’s involvement in the Museum of Shakespeare project:

“The way they will interpret the museum is great. Not everybody engages with heritage in the same way. If you have a museum that looks like every other museum it will attract people who go to those types of museums, but there’s a broader spectrum of folks that I think will actually go through the doors because of the content.”

Bompas and Parr’s design means the museum will reach audiences that it wouldn’t have reached otherwise:

“That has to be a good thing.”

The remains of the Curtain Theatre will be the highlight of The Stage, a £750m mixed-use scheme. This will feature homes, retail, restaurants, cafés, office space, a performance area, a park and a purpose-built visitor centre for the Curtain Theatre.

A fascinating project

“From a creative perspective, this is a fascinating project,” Sam Bompas tells blooloop:

"It’s also pretty intimidating. We are working with an awful lot of Shakespearean experts. You can spend an entire life studying the subject, and not touch the sides. Going into bookshops with Shakespearean sections, you find vast reams written about every aspect of life. We have to crystallize that down to an experience that can be enjoyed by experts and children alike.

"Our solution to all of it lies in the fact that Shakespeare really works well when it is performed. It becomes understandable.

"We are also very interested in the question of what museums should be, and what they should do. If we go back to the archaic term ‘museum’, in Greek it is ‘mouseion’. This means “seat of the Muses”’, a place for contemplation. What we want to deliver is a place where you can go and find your individual muse. Shakespeare is the vehicle through which to do that.

"And then, of course, we ultimately want to put you on the very same stage where Romeo and Juliet and Henry V were first performed, so you are put at the very centre of the story.”

This aspect, he says, is marvellous:

“It has this terrific authenticity. We’re then able to build on that with creativity, technology, science, play, and to create something that we hope is really rather remarkable.”

Immersive experiences at the Museum of Shakespeare

The technology being used is both immersive and multisensory.

For Bompas and Parr, an ‘immersive’ exhibit is one informed by a narrative that is often supported by academic research, whether that is cultural, historical, scientific, or all three. The audience has genuine agency, and participation is encouraged, though not mandatory.

Set design, of course, is spectacular, and has dynamic elements, where elemental content and interactive elements play a role. Performers may be involved, and the design is polysensory, the senses articulating the narrative. Technology, often invisible, is invariably in service to the story.

“We're going far beyond the many video projection installations that exist now,” he comments.

Interpreted through Bompas and Parr’s idiosyncratic vision, the Curtain Playhouse will be, first and foremost, a museum.

Bompas contends that museums are places for inspiration. Visitors should, therefore, be able to find their personal inspiration. The perception of the time spent walking around a museum can, he suggests, be expanded through differentiated spaces, stimulating experiences, maze-like construction, and multiple content-creation opportunities.

Techniques, approaches, and technologies from other disciplines – theatre, film, SFX, musicology, science, gastronomy, and ancient crafts can be leveraged to offer compelling experiences.

The title ‘museum’ confers a measure of authority and, therefore, responsibility – but museums can be puckish, too. The museum doesn’t stop at the limit of the premises but exists in people’s minds and their onward practice, the digital realm, and in the cultural custard.

Reaching a wider audience

In terms of being a museum, Bompas adds:

“We’re lucky in that, while we do have some very important archaeology to present to the public and preserve for the future, unlike some of the major museums, we don't have a huge collection to maintain. It comes with some advantages in terms of how we get to redefine what museums are.”

Bompas and Parr’s involvement in the project ensures the new museum will also reach beyond the usual visitorship of a Shakespeare-themed museum.

“Shakespeare played with the universals of humanity,” Bompas says. “That's why the work is still being performed all the way around the world by lots and lots of different people, presented to illustrate and tell lots of different stories, even though you're working with the same script."

"Part of that comes, I think, from the constraints that Shakespeare had, some of them around censorship. You wouldn't want to tackle anything too topical that would potentially put the production at risk. You had to talk about something that really got to the very centre of the different aspects of human experience. The good thing about this is that whenever we hit a challenge, we could look to Shakespeare to try and answer it.

"How do we get to the centre of what human experience actually is? One of the things that museums and even immersive productions - whatever they are - don't always facilitate is human connection. Theatre, too: you're sitting in the dark watching some people on the stage.”

Storytelling at the Museum of Shakespeare

This is something Bompas and Parr are addressing:

"We are making a lot of design decisions focused on getting people to speak to and bond with other people. They will also be the audience later on, so if you have those interrelationships, and you’re doing your soliloquy, you realise that all those marvellous solo features in Shakespeare weren't soliloquies, but rather dialogues with an active live audience who were participants.

"That, I think, is one of the things that is slightly lost in theatre now. Through building relationships across the show people will then be able to have that much more participatory Elizabethan experience.”

Additionally, he says:

“We want people coming out having learned more about what it all meant.”

He explains how this will be achieved:

“The object-based storytelling that is the traditional approach of museums is still very valuable. The objects themselves don't even need to be very precious. For humans, any object can be a remarkable portal through which to step, to understand reality. Even the most mundane ones can be presented in interesting ways.

"But also, in terms of what a museum is, we're interested in breaking down the borders of museums and having lots of relationships with other experts and organisations. We've got dialogues with all the Shakespearean organisations in the UK.

"Here, the visitors will be performing Shakespeare. We'll make sure that when they do so they'll be sensational, but they might also want to go and see some really good Shakespeare productions in Stratford, or at the National Theatre or the Globe. We want to encourage that.”

A site of international significance

The new Museum of Shakespeare is located in Hackney on the border of the City Of London. However, it also has national, and, in fact, international significance:

“Shakespeare is one of our greatest cultural exports,” Bompas says. “Some people even say Shakespeare's better performed in other languages because you're not so constrained by previous productions. You’re forced to think about what you present, the words you use, and their relevance.”

Freed from the prison-house of language, the drama can then transcend its form.

“Whenever it has been performed, Shakespeare is edited,” he points out. “A lot of the written plays are four hours long, but a Tudor performance would be two hours. They were editing them even in Shakespeare's day.”

Commenting on how the archaeological exploration has changed some of the assumptions that had been made about Tudor playhouses, he says:

“This playhouse was rectangular, which is remarkable. The Shakespearean academics we’re working with say this was effectively the IMAX of Tudor London. The bigger stage meant that it was where you would put on the big action productions with all the fight scenes.

“Another great takeaway is also understanding that many of the audience were going to the theatre to watch the fighting. It was a time when most men carried weapons. There were ordinances that tried to limit the size of the sword that could be carried. In London, you could have a sword over a metre long. We now tend to see Romeo and Juliet as a great romance. But in fact, much of it is just the setup for some fantastic fights."

Working with the experts

Commenting on the experience of working with the MOLA on the Museum of Shakespeare project, Bompas says:

“They’re really good. It’s such fun working with total experts.”

While not a Shakespearean scholar before this project, Bompas has been immersing himself in Shakespeare productions. He says:

“How we relate to it is by trying to find those things that are universally appealing. Shakespeare is, once you get over the language, the most accessible of things. It is about the universal human experience.”

Erik Neergaard

Erik Neergaard Phil Hettema

Phil Hettema