Opened in early March by the Dutch King Willem-Alexander, the new National Holocaust Museum in Amsterdam opened its doors as the Netherlands began a year of commemorations to mark 80 years since its liberation from the Nazis.

Eight decades on from that moment — and almost two decades since plans were initiated to create the institution — it is now the first and only museum to tell the history of the persecution of the Jews in the entire Netherlands.

There are a number of sites telling chapters of the Dutch Holocaust story. The most famous is Amsterdam’s Anne Frank House, which welcomes over a million visitors a year. Yet, there has never been a museum dedicated to the whole story of the persecution and murder of Dutch Jews in the 20th Century.

That’s now changed, as this horrifying history is recounted on the Plantage Middenlaan in the heart of Amsterdam’s Jewish Cultural Quarter.

Opening the National Holocaust Museum

Across three floors and through 2,500 objects, visitors to the National Holocaust Museum journey through several galleries. These explore the day-to-day life of Jews on the eve of the Second World War before moving through to the persecution they suffered when the Nazis seized power and followed by the steps that led to the eventual mass killing of 102,000 people.

At three-quarters of the total number of Jews in the Netherlands at the time, it was the highest proportion of Holocaust killings in Western Europe.

Despite the difficult subject matter, people have flocked to explore the new institution. On the first days, there were queues down the street to get in.

The opening was “quite something” head curator Annemiek Gringold said at a press tour of the new museum. “I am on a high adrenaline level.”

Gringold said this was not only because the museum’s public unveiling was televised live and attracted “many, many viewers”. They also received endorsements from groups of Holocaust survivors who were the first invited guests to see inside.

“We felt entrusted to tell their stories,” Gringold says. “They came to see how we display their history.”

That emotion was intensified by the fact that some of these survivors—now in their 80s and 90s—had been within the museum’s walls as very young children. The building that now houses the museum was previously the site of an incredible story of bravery and resistance.

A site of humanity

From 1942, the Nazis ordered Amsterdam’s Jews to assemble inside a theatre on Plantage Middenlaan Avenue. At the time, this was the city’s most predominantly Jewish neighbourhood. Inside this theatre, they were imprisoned for hours, days, or even weeks before being sent to death camps including Auschwitz.

Children under 12 were separated from their families and held in a kindergarten on the other side of the street. This was purely to make administration easier for the Nazis. The children, too, were to be transported to their deaths.

But thanks to the extraordinary bravery of the kindergarten staff, hundreds of children were successfully smuggled away to safety.

In a system that required huge secrecy, staff moved children to a teacher training college next door. They were taken down a side corridor and ushered out onto the street where they were handed to resistance couriers. They then fled with them to safe houses across the country. Trams — which brought the Jews to the avenue in the first place and which still rattle along the street outside to this day — provided the cover.

That former college building now houses the National Holocaust Museum.

Across the 16 months the Plantage Middenlaan was used as a deportation site, 46,000 Jews passed through. Nearly all were murdered — but the brave staff managed to help 600 children escape.

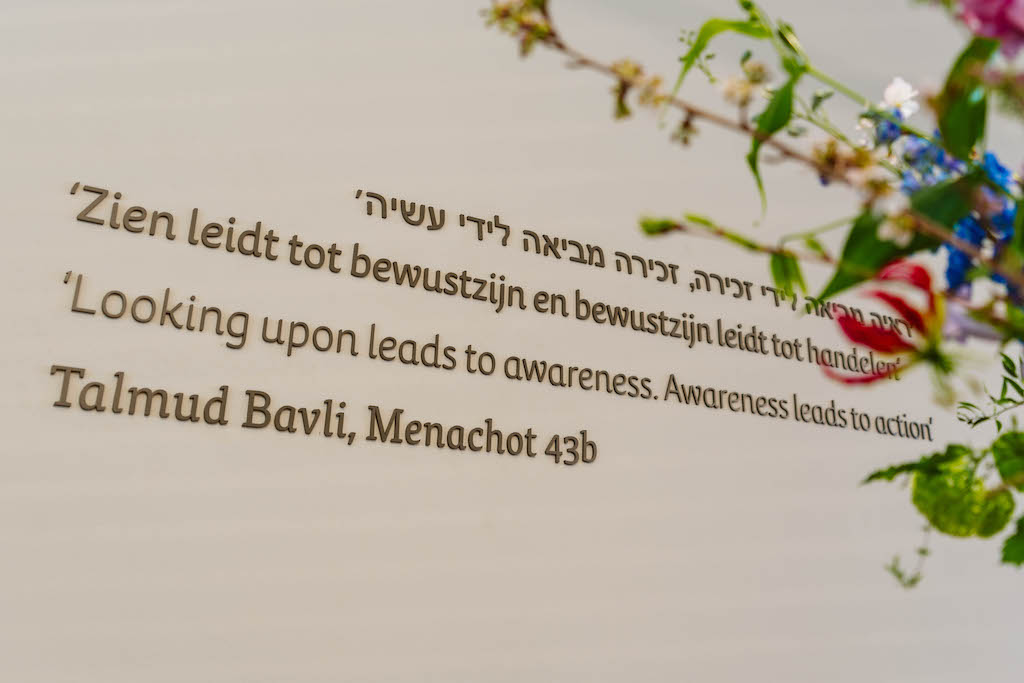

“At great risk to their own safety, they saved the lives of Jewish children,” Gringold says. “This [museum] is a site of absolute humanity.”

Bringing history to life at the National Holocaust Museum

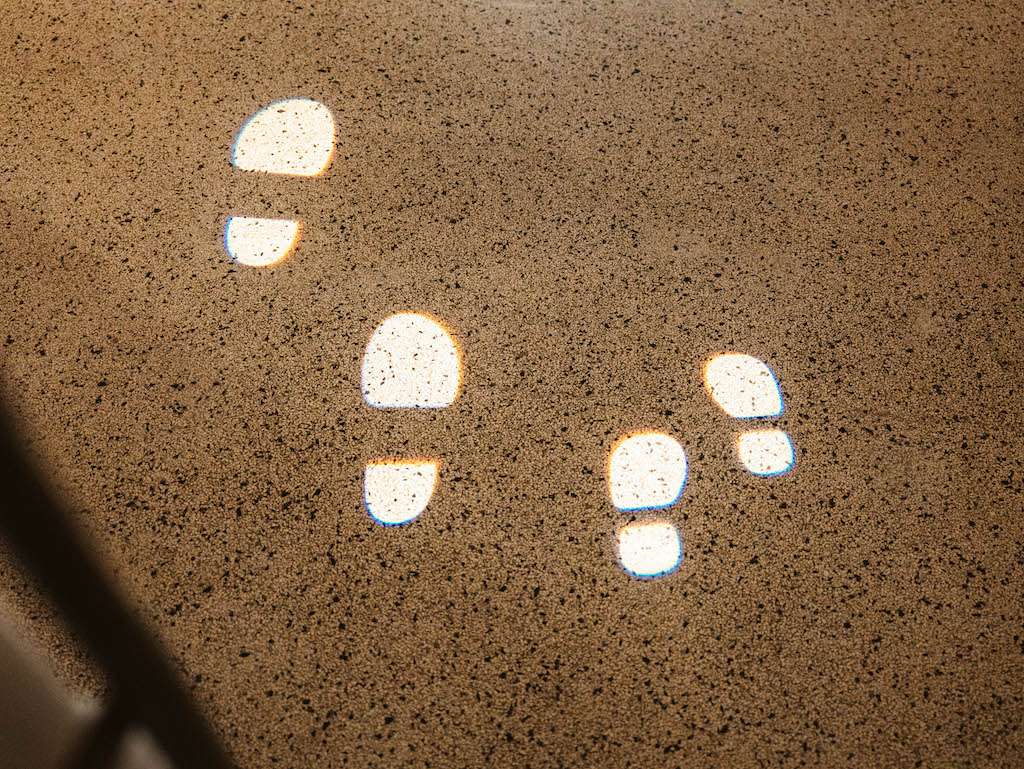

The escape corridor is still there, fully preserved and part of the visitor route. It is kept in the relative darkness that aided the staff’s plans. However, there is now a light installation projecting children’s footprints down the corridor.

One survivor has remarked of the new museum: “It happened here. You can still smell it.”

It is in this spirit of humanity that the museum has been created. It commemorates the sacrifice of those who risked their lives to free so many young children. In addition, it re-humanises the tens of thousands of Jews who didn’t survive.

“The Holocaust was a system of dehumanisation. We want visitors to realise that the dry statistics of the destruction of Dutch Jewry are about individuals,” Boaz Bar-Adon of OPERA Amsterdam, who designed the permanent exhibition spaces, said of their work. “We approach the victims…on an individual level.”

One way OPERA has achieved this is through nineteen bespoke display cases across the galleries. Each highlights a single, named person’s life.

“To tell the personal stories of the victims, we have developed Forget-Me-Not. This is a tribute in the form of a uniquely designed showcase with space for personal objects, photos and memories”, Bar-Adon explained.

“Don’t forget us”

These cases also contain video and audio fragments where possible. This helps each Forget-Me-Not bring the life of a Holocaust victim into sharp focus for visitors. Touchingly, this innovation took inspiration from a surviving object — a card frame with three passport photos of unknown victims alongside a written appeal: ‘Don’t forget us!’

Similarly, the rear garden takes its name from the initiator of the rescue mission, kindergarten director Henriëtte Pimentel. After being arrested by the Nazis in April 1943, Pimentel was murdered in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Her legacy, however, is now front and centre in the location where she embarked on such an act of bravery.

Twelve months before the museum’s opening, to dedicate the garden to Pimentel, three of the children she had helped escape came to the site—“in the midst of all the construction”—with their own children and grandchildren to plant trees. “We brought life here,” Gringold says.

The museum collection

To create the displays, the National Holocaust Museum team needed to source and bring together objects for the first time. Across the museum, around 2,500 objects are on show, “including photos and films” and other documents, according to Gringold.

Objects are from the museum’s new collection, but many are on loan, including from cultural and historical institutions. In addition, individuals have given around 200 artefacts. “They have entrusted their artefacts with us, which are usually very dear to them,” Gringold explained. This includes many of the objects in the Forget-Me-Not displays.

The museum plans to acquire more. However, these will mainly be for future temporary exhibitions rather than going into the permanent displays, which have been designed to last around ten-to-15 years before they need revamping.

Most of the items that visitors encounter are modest, everyday objects. Yet they pack a huge emotional punch due to the history they tell and the lives they reveal.

One of the most moving is a simple wooden table football game. This belonged to Nico, an only child who recieved it for his birthday and who played with it with the children next door. He gave it to them when he and his family were ordered to report for deportation. Nico and his family were murdered just weeks later. Nico was 11 years old.

The National Holocaust Museum building

There’s a modesty, too, in the building that now houses these items. But it is a building that fully befits them. The conversion of the former college into a museum is thoughtful and delicate. This has resulted in a magnificent architectural space.

Architects Office Winhov was responsible for designing a transparent, light museum building within the existing structures. The ultimate aim was a museum building that encouraged reflection.

The desire for light is also a deliberate symbolic choice. When the horrors of the Holocaust so often happened in the darkness, the natural light that floods certain areas of the building is a way to symbolise that these stories need to be told in the open.

“Our buildings are in what was once a bustling Jewish neighbourhood. Exclusion, deprivation of rights, detention and deportation took place here. Yet there was also a rescue: a light in the darkness. For a long time after the war, this site symbolised our inability to deal with what happened” Gringold says.

Design challenges

Architects Uri Gilad and Inez Tan say that “the biggest challenge was to create a space that would present the local history in a respectful manner and at the same time leave room for a genuine historical experience. We and our team strongly believe that architecture can enhance the imagination and the awareness of museum visitors.”

The project included significant architectural work on the surviving college building, while the Kindergarten building is no longer there. The team has restored original features, including the central staircase and the tiles in the children’s escape corridor.

“Today it is a place for remembrance and commemoration and a warning showing what people are capable of,” says Gringold.

That warning is most apparent in the top-floor gallery of the National Holocaust Museum. This explores the insidious and creeping persecution Jews suffered after the Nazis seized power.

The texts of hundreds of new laws the Nazi occupiers in the Netherlands enacted to discriminate against Jews cover the walls from floor to ceiling. It is overwhelming but a deliberate design choice to show how the Nazi regime — assisted by Dutch civil servants — dehumanised Jews long before the mass murder began.

The National Holocaust Museum’s audiences

The museum is targeting a large and broad audience, with an ambition of 100,000 visitors in 2024. It believes these visitors are likely to be people with an interest in cultural history and people with a personal relationship to the Holocaust. It will bring in tourists from the Netherlands and beyond.

Schoolchildren are also a major target audience. In the first four weeks, the museum has already had 50 school groups visit as part of their formal learning.

For museum staff, attracting these audiences is vital. They’re increasingly concerned about the poor information that circulates around the Holocaust today. Knowledge of the atrocity is fading as it passes into historical memory.

For example, in 2020, a nationwide survey of Americans under 40 revealed that 63% did not know that six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. Almost a quarter of respondents — 23% — said they believed the Holocaust was a myth, or had been exaggerated, or they weren’t sure.

The museum’s communications spokesperson Boris de Munnick says:

“We do worry about the lack of knowledge, the amount of misinformation and lack of accurate historical knowledge young people have.”

He says the museum team are happy people can now visit this museum “so we have the opportunity to increase their knowledge and understanding of the Shoah.”

Kamp Westerbork — a shared mission

With that same survey revealing that almost half of young Americans could not name a single concentration camp or ghetto established during the Second World War, it is no surprise that increasing knowledge is also an ambition shared by many of the Netherlands’ other institutions and visitor sites that tell aspects of this story.

Highlighting their shared goals, de Munnick says:

“We work together with museums such as the Anne Frank House and Kamp Westerbork in teacher training, professional development, international study trips for educators and several international projects such as the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance.”

Kamp Westerbork was a transit camp for Jewish prisoners 110 miles east of Amsterdam, deep in the Dutch countryside and very near the German border. There weren’t killings there. But the vast majority of Dutch Jews passed through — including nearly all of those from Plantage Middenlaan — as part of their forced journey to death camps. Anne Frank was held here for around a month in 1944 before her transport and eventual murder in Auschwitz.

Urgent work

Westerbork is now an expansive visitor site and museum. It features the National Memorial dedicated to those imprisoned at the camp.

“We contributed to the development of the National Holocaust Museum by sharing knowledge and objects from our collection,” says Westerbork’s director, Bertien Minco.

She adds: “We see decreasing knowledge about the Holocaust and increased polarisation as a major problem for our country. We live in a period of transition. The generations that lived through the war are almost gone. But the traces and traumas of the war are still very much present in society.

“It does reinforce the urgency of our work and the need for a major renewal.”

That renewal is about to begin at Westerbork.

Very little of the actual camp remains. What is still preserved is located some 3km away from Westebork’s Visitor Centre. So there’s a challenge in how to provide a fulfilling and cohesive visitor experience.

“The biggest challenge is enabling visitors to experience the site when almost nothing remains of the original camp,” Minco says. “We are currently in the developmental phase. The overhaul will include a renovation of our museum building and redesign of the visitor experience on the former campgrounds.”

Looking to the future

It’s clear that for both the National Holocaust Museum and Kamp Westerbork, the teaching of the Holocaust atrocities needs to endure. It also needs to be constantly renewed.

“In 2000, there was the assumption…that with the change of the millennium, there would be less interest in the history of the Second World War and less interest in the history of the Holocaust. They were proven wrong” Gringald says.

But she adds that “we felt there was a need to tell what happened here in the city centre. A new generation needed to know and that’s why we started to think about creating a new museum.”

Survivor Flip Delmonte is one of the 600 young children helped to safety on this site. At the opening, Delmonte summed up the urgency of the museum’s mission: “The Jewish people were murdered. There are people, children who survived and we cannot forget them. They must be remembered also in the future.

It may have taken 80 years for the museum’s doors to open. But the next 80 years will be more vital than ever in remembering this story.