Edmonton Valley Zoo is in the process of a revitalisation. Its Director, Denise Prefontaine, talked to Blooloop about the vision for the zoo and the inspirational Wander Trail that interprets the Saskatchewan River Valley in a unique way.

“I’m not a biologist or a zoologist and as a child I didn’t have a passion for conservation or animals or working in a zoo environment, " says Prefontaine. “It was something I never contemplated. I had a strong passion then for community development and for recreation as a means of developing community.“

Her original degree is in recreation administration. Through that, she became interested in facilities as hubs of community. She started to focus on facility management before doing an MBA in research, specialising in consumer behaviour.

Prefontaine had always worked for Edmonton’s Municipality; the zoo is one of a number of facilities it operates. About twenty years ago, a job in marketing was advertised at the zoo and, given her focus on consumer behaviour, Prefontaine felt it would be interesting. Having worked on the community development side for her department, she now came into the facility side.

“And, it was then that I started working with Becca Hanson [of Studio Hanson Roberts Architects]. At that point in time we were working on a master plan for the zoo. Becca is an incredibly inspiring person. She’s a storyteller. And, she began to weave a story for us about the zoo, and where this zoo could be, and our role in the world, rather than confining ourselves to being a little municipal facility. That was really quite eye-opening for me in a lot of ways.”

There followed a hiatus when a reorganisation saw all marketing staff moved back downtown, but Prefontaine was fascinated by the zoo and as soon as an opportunity presented itself, she moved back.

"There’s something about the passion of the people who work at this facility."

“… They’re an incredible bunch, and what they aim to do and how they aim to make a difference in the world was at the core of what I had started to become. So, when I knew that there was an opportunity to come back here, I kind of put my hand up and said: I want to do that.”

Prefontaine was keen to return and help the zoo go on the journey that it had started. Typically, as with many small municipally-funded facilities, the zoo lacked a bold direction. Prefontaine explains:

“ – it wasn’t taking giant transformational leaps. I wanted to come back and make a difference for the zoo and for the staff here and for their passion so that they could really start to make a difference in the world.”

In her role in market research she had been part of the team that developed a master plan, approved in 2005, for the zoo.

A year later, she returned as Edmonton Valley Zoo's Director, and oversaw the implementation of elements of that plan.

It was a zoo that had big ideas and was operationally very different from when it was developed in 1959, but physically and structurally it remained essentially unchanged and in desperate need of modernisation.

“We took that opportunity to say…this, for us, is about being transformational. It’s not just about improving the facility; it’s about changing the way people view this facility and the understanding of it… so we did lots of ‘vision and mission’ exercises with the staff… Our vision statement is that we will be a special place that inspires love and learning of animals and nature. And, we build that around four different pillars of what we do: stewardship, conservation, education and engagement. We think if everything we do falls into one of those areas and we cast everything against that, we’ll start to grow and develop.”

Conservation is one of the zoo’s primary focuses.

It is involved with a number of initiatives including the Species Survival Programme, working with the Snow Leopard Trust and Red Panda Network. Sustainability is an important consideration when contemplating capital development. The Polar Exhibit, for example, which has 850, 000 gallons of water in it, is a completely self-sustained system. The only water replaced is that lost due to evaporation. There is both mechanical and biological filtration: the system is mechanically filtrated but the backwash goes into the biological filtration of the wetland and is then fed back into the system.

In building projects, reclaimed wood is used as much as possible. Prefontaine adds:

“And, then we try to take advantage of other opportunities. Our location is built on an old gravel-pit. Any time they’re doing construction here, they find lots of very large rocks. So, when they dug the polar exhibit they dug a 25-foot hole for the big pool and they took out huge boulders – one was the size of a Volkswagon. A lot of the boulders you see on the Wander are from that other project: our seating is made from those boulders, cut in half.”

People were beginning to understand and engage with the zoo’s vision, but there were some operational changes that needed to be made: the zoo was still functioning with some old exhibitory and an outdated facility.

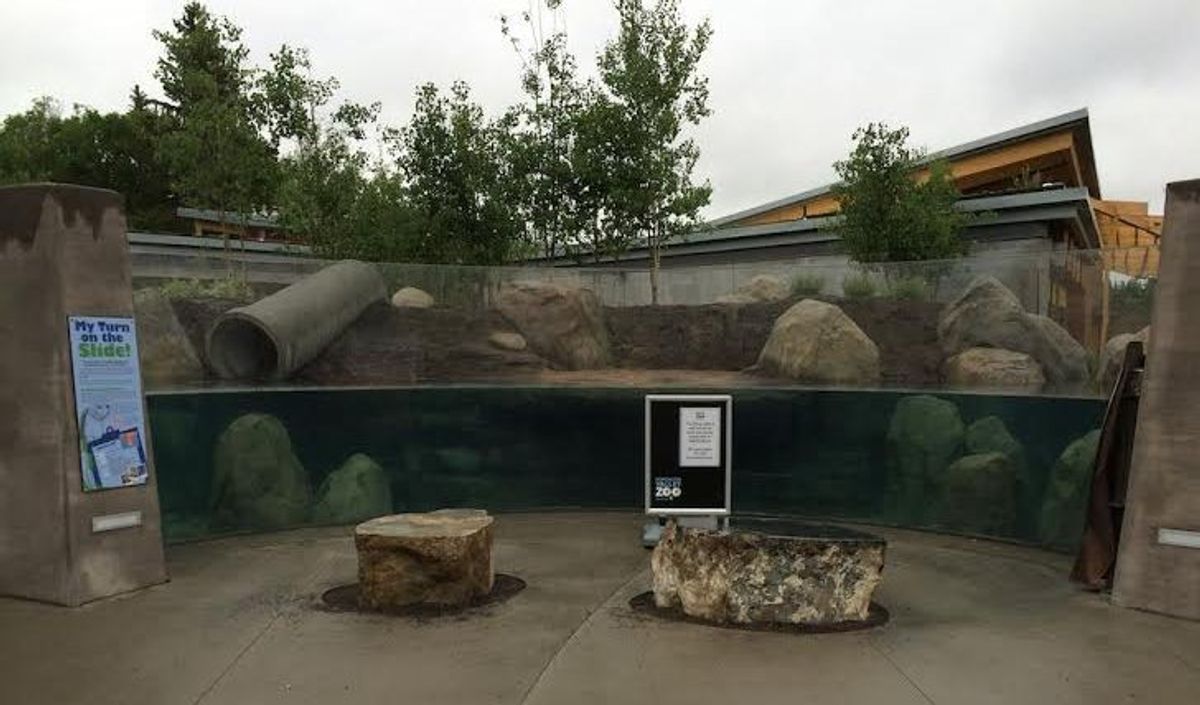

The first change made was the creation of an Arctic exhibit for the seals, as the 1959 seal exhibit was, as Prefontaine puts it, “completely unacceptable.”

“Our Arctic exhibit is about culture and environment and sustainable practices.”

It took two years to build and Prefontaine says the open day was a “wild moment. Our mayor came to do the opening, and he was running a little late and I was walking behind him as we were hurrying to get over to the area. The way the exhibit is designed you kind of walk into it, and he went: “Wow.” And, I thought: Okay. We got it. We did something right. And, so that was really sort of the eye-opener, I think.“

The next phase was the Entry and the Wander Trail: a circulation path, conceived as a way to contextualise the zoo and an interpretation of its location. This was the brainchild of architects Studio Hanson Roberts, who were in on the zoo’s transformation from the beginning.

The Entry comprises an education building, a gift shop, a café, and a huge gathering space where the zoo held a dinner for six hundred people which, Prefontaine says, didn’t fill the space.

“So it’s a huge space – but it doesn’t feel huge. It feels that you’re being very welcomed; it’s an intimate space, though it’s quite large. I think our design team, Becca and David from Studio Hanson Roberts, who worked with a local architect for some of the building - they nailed it – they wholly nailed what we needed to do.”

The Wander - an inspirational journey into the landscape

“We wanted people to understand that they were in Edmonton, and further to that, that they were in Alberta. Our Wander is really an interpretation of the North Saskatchewan River Valley as it winds through Alberta. Our gate – our front entrance – is Edmonton, then as you walk along the Wander you are walking back up the river towards its headwaters up in the glacier.”

The Wander is very different from a typical zoo exhibit – the only animals in it are otters and a trout lake. Instead, it is a reflective, interpretative and inspirational journey into the landscape.

“So we spoke with elders from different communities and talked to them about the river and why it was important to them; what it meant to them. And, we spoke with fishery biologists about the fish in the river. And, so the Wander has a variety of different interpretative elements to it that are kind of almost hidden – that you have to think about and you have to participate with.”

The Wander is designed as a river but sometimes the river is real water and sometimes it’s an interpretation of water; there is a trout pond and a beaver dam that feeds into the trout ponds. Species of fish that call the North Saskatchewan River home are embedded as decorative bronze rubbings, and wetlands have been incorporated into the pathway.

"The kids can play in those rocks, move rocks around and change the way the river moves"

“We often get asked by visitors for play areas. We didn’t want to do a play area that looked like a play area. So, the very top of the Wander – the Meltwater Play – is where the river starts in Columbia icefields, and then the water comes out of an ice cave and there are little rivulets that go through all these rocks. Then they end up in a pool and then that becomes the trout pond when the beaver dams it up. And, the kids can play in those rocks. They climb all over them, they move rocks around, they try to change the way the river moves. It’s fascinating to watch because it is a play space that children are interacting with in an environment that’s unusual for them in an urban setting. It’s quite fabulous. I’m fascinated by it.”

At times during the creation of the Wander Trail, doubts crept in, and the team wondered how it would be received by the public.

“When you’re building a zoo exhibit that doesn’t feel like a zoo exhibit, you’d expect to have a big iconic species or something like that, but instead we have a pathway. And we’re looking at it and thinking, well, we think it’s fabulous, but people are going to come and say – where is this animal? We knew we needed to do this first before we could start building the next stage…”

The team knew that the function of the Wander was to draw people in, to begin them on a contemplative journey, before they reached the more traditionally zoo-like area. But, would people understand?

The answer turned out to be a resounding ‘Yes’.

“It has been overwhelmingly positive. People are loving what they’re seeing. And, they get it.”

"Intimate, inspiring, natural, nurturing, cool - we hear those words about the Wander."

“When we talked about our vision and our mission we wanted our brand personality to be about different aspects, and one of the words we used to describe our brand personality is ‘intimate’. And we also used ‘inspiring’. And we used ‘natural’, and we used ‘nurturing’, and we used ‘cool’. Those are the five words we use to describe the kind of zoo we want to be and how we want you to think about us – and we hear those words about the Wander.”

COST of Wisconsin was the project team responsible for executing Studio Hanson Roberts’ vision and constructing the Wander, which involved shop drawings, exhibit models, the fabrication and construction of the otter exhibits, trout pond and the meltwater area.

Jason Burnie, Project Manager at COST of Wisconsin, spoke to Blooloop about the unique challenges and solutions inherent in the project.

“Studio Hanson Roberts was the architect who came up with the design and created it along with the zoo. We just kind of executed it.”

He describes working with the Wander’s architects:

“It was kind of collective. They would come up with, Hey – we’re kind of thinking this, and so we would shoot some concrete and carve something and they would say yay or nay, and we would collectively come through as a team. And it was a pretty unique process.”

Speaking of the challenges involved in the construction, he says:

"We had these unique slightly mountain range-ish looking rocks that were standing up, but they were on a 30 degree tilt, which made the engineering fascinating. We were building models and making rocks tip over forever. There was actually a big concrete structure under each of these rocks to hold it in place, but having our engineer figure it out through models took some time and it was some of the more unique engineering that we’ve had to go through.”

And then there was the weather...

“We had a couple times when it was proper monsoon style rain, and it would wash everything down that hill. I remember getting some photos from my superintendent Jesse, and everything was washed down where there’s one of the pools right now - everything slid down the hill. Trying to work through those and still maintain a schedule were some of the most challenging things… But I think we maintained the schedule pretty well. I know that our relationship with the general contractor and also with the zoo itself really helped that...We actually snuck in another little project for the director while we were doing this one – over in the squirrel exhibit to kind of help them out.”

Fired with enthusiasm for the project, COST of Wisconsin contributed to the ideas process and the final look of the exhibit.

“One of the other cool features about this one was initially, when they called out the specifications for the glass, typically you buy that kind of laminated glass in eight foot sections, and the pieces get fused together but you can see that kind of vertical line, you know? Well, we decided that it would be cooler to try to get a single piece of glass.”

There are only two manufacturers in the world who can supply glass in sections of a sufficient size, and it took eight months for the glass to arrive.

“We built it into the schedule so it was ok – and I think the end result is amazing because you don’t have those laminated glass vertical lines – just that full 39 foot sheet, and it looks really cool: it adds to the exhibit and looks less man-made.”

The next stage of the master plan for Edmonton Valley Zoo is in progress.

Prefontaine elaborates:

“At the very start of the Wander is an area called the Crosswinds Plaza, and the interpretation there is how the winds move through Alberta, and the migratory pathways of the birds. For us, it’s also a decompression zone where you can go one way or the other. So right now we’re actually taking a step back from the Wander and going the other way. Our next phase of development is to take our original zoo which was built in 1959 - the inner heart of the zoo – it’s going to be our family zone, and we’re building that.”

This section, Prefontaine says, is called Nature’s Wild Backyard, and will have families exploring the world from the perspective of the animals, forging an understanding of: “…relationships in the land, on the land, above the land and under the land and between land and water. It’s a whole new exploration for us.”

Images: construction and wander photos kind courtesy Cost of Wisconsin, animal photos kind courtesy Edmonton Valley Zoo.

TM Lim and Adam Wales

TM Lim and Adam Wales

Toby Harris

Toby Harris Hijingo

Hijingo Flight Club, Washington D.C.

Flight Club, Washington D.C.

Flight Club Philadelphia

Flight Club Philadelphia Flight Club Philadelphia

Flight Club Philadelphia Bounce

Bounce Hijingo

Hijingo Bounce

Bounce

Fernando Eiroa

Fernando Eiroa

Nickelodeon Land at Parque de Atracciones de Madrid

Nickelodeon Land at Parque de Atracciones de Madrid Raging Waters

Raging Waters  Mirabilandia's iSpeed coaster

Mirabilandia's iSpeed coaster Parque de Atracciones de Madrid

Parque de Atracciones de Madrid Ferracci at the ribbon-cutting ceremony for Nickelodeon Land at Mirabilandia, with (left) Marie Marks, senior VP of global experiences for Paramount and (cutting the ribbon) Sabrina Mangina, GM at Mirabilandia

Ferracci at the ribbon-cutting ceremony for Nickelodeon Land at Mirabilandia, with (left) Marie Marks, senior VP of global experiences for Paramount and (cutting the ribbon) Sabrina Mangina, GM at Mirabilandia Tropical Islands OHANA hotel

Tropical Islands OHANA hotel Elephants at Blackpool Zoo

Elephants at Blackpool Zoo  Tusenfryd

Tusenfryd

Andrew Thomas, Jason Aldous and Rik Athorne

Andrew Thomas, Jason Aldous and Rik Athorne