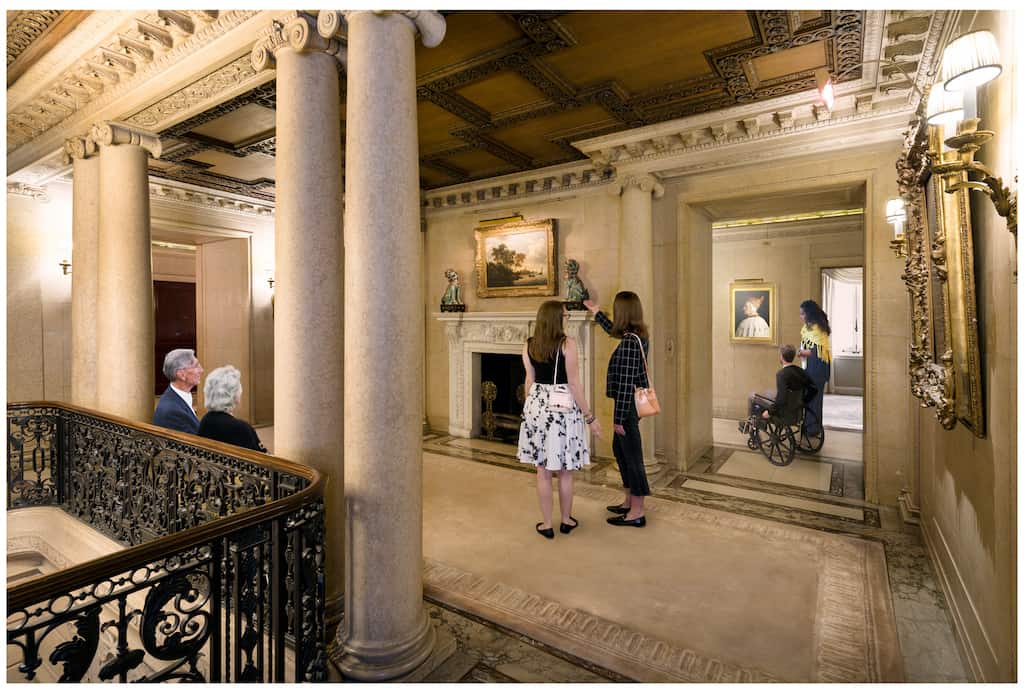

In March 2021, The Frick Collection moved to a temporary home in the iconic Breuer Building on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. This new venue, Frick Madison, allows visitors to continue enjoying the museum’s stunning collection of Old Master paintings and European fine and decorative arts while its permanent home, the Henry Clay Frick House, is being renovated.

The renovation project will see the mansion’s second floor being opened to the public for the first time. New facilities will be added, and the project will bring improvements to the museum’s accessibility. The building’s infrastructure is also being updated.

With the refurbishments well underway and the collection’s first year at its temporary venue completed, we spoke to Ian Wardropper, the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Director of The Frick Collection, to find out more about the renovation project, and to see what guests can expect from a visit to Frick Madison.

A career in the arts

Wardropper was a long-time fan of The Frick Collection before he took on the role in 2011, as he explains:

“I studied art history in college and did my graduate work in New York City in the 1970s. When I was here as a graduate student, the Metropolitan Museum and the Frick were the two poles of my interests. Later, I ended up working for both institutions.”

Wardropper’s first job was at the Art Institute of Chicago. He worked there for almost 20 years, before moving to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2001.

“I was the chairman of the Department of European sculpture and decorative arts at the Met. It’s one of the largest holdings in the world in that field; an enormous department with 60,000 objects, sixty galleries and 10 curators. I had a wonderful time there and then moved to the Frick. It’s a much smaller place, but that is one of the things I like about it.”

“I have always admired the Frick. The trajectory of my career had taken me, having done teaching, scholarship, exhibitions, and acquisitions, to a role where I was more and more in charge of a larger entity and in some ways more of an administrator. I found that I enjoyed trying to help curators bring their projects to fruition. So, there came a moment when I thought becoming a director was the next step. That’s when I ended up coming to the Frick.”

The Frick is a unique collection

Speaking about what makes The Frick Collection unique, he says:

“We’re in a different venue currently. However, in a way that underlines even more what I love about the permanent home of The Frick Collection, which is that it’s the combination of a first-rate collection with a fine house for which the collection was intended. There is this marriage of the two which is greater than the sum of the parts.”

Wardropper says that the small scale of the collection and the spaces is a big part of its appeal:

“My goal is to bring the public back to the kind of pleasure which first sparked my interest in art. That is being able to look closely at a work of art in a setting that didn’t make you feel you have to keep moving because other people were coming in. I want visitors to be able to really take their time enjoying a work of art.

“That is one of the things which I think makes the Frick a special place.”

Becoming Frick Madison

When plans for the renovation of The Frick Collection were approved, the museum was in the position of having to either find a new home or move to a temporary venue.

“The construction project is so all-encompassing that we soon realised the whole collection would have to be moved for safety, and all the staff would have to move out. Initially, we thought we would put everything in storage and that we would close for three years.

“However, I started seeing if there was someplace in New York City, some museum that might have a gallery or two where we could show part of the collection. I ended up coming to the Breuer Building, which was purpose-built in 1966 by Marcel Breuer for the Whitney Museum.”

“The Whitney had moved to a new museum downtown, but it continued to own this uptown building. They first leased it to the Metropolitan Museum for eight years. The Met did some wonderful shows when they were here. However, it proved to be costly for them to run it. So, when I came along looking for a place to see our collection, very quickly, we went into discussions over the Frick taking over the entire building.

“So essentially, we are subleasing from the Met, which is leasing from the Whitney. It is a partnership among the three museums.”

Continuing to show the collection

There were several benefits to this arrangement. Firstly, the timing was perfect. In addition, the Breuer Building is big enough to hold everything in the museum’s collection.

“This allowed us to move the entire collection under one roof, so we can store everything in the same building. That’s very important to any museum when it comes to controlling the security and the climate. There is also room for our entire staff, meaning we can continue our other work, like photography and conservation.”

The most important thing, however, was to be able to continue to show the collection, says Wardropper. This was where the building threw up some challenges:

“We quickly dismissed the idea of trying to show the collection the way we do in the mansion. For instance, with silk wall hangings and huge fireplaces and all of that.

“This brutalist building is almost the antithesis of the mansion; we have to accept the severe walls. But the advantage was that we could build out the galleries however we wanted. So, we engaged Annabelle Selldorf, who is the architect in charge of the renovation of the mansion, and we asked her to design a series of galleries that would match what we wanted to do, showing our collections on three different floors.”

New ways of approaching the pieces

What’s proved to be interesting is that the Frick ended up showing its collection in what, for most museums, is a fairly conventional way, by country and by period.

“But for us, we had never done it that way. Traditionally the Frick, in some ways, is an anti-museum; we don’t show things by period. We show things in the way that a private collector would. This has been a chance for us to review our collection, we have thought about it in new ways.”

“I worried about the traditional audience, that they might not like it. But almost everybody has enjoyed it, because they’re learning new things about the collection, as are we. One of the things I like about that the most is that people are starting to re-appreciate how good our collection is, how good the paintings, the decorative arts and the sculpture are.

“For a frequent visitor to the Frick at the mansion, the paintings can end up seeming part of the décor. But now we have stripped all that away, people can really look at the paintings. And they are reminded that it is a truly great collection.”

Lessons learned from Frick Madison

Will the team take some of these lessons that it has learned at Frick Madison back to its permanent home at the end of this project?

“We haven’t completely finished our plans for how we use the display space in the renovated building,” says Wardropper. “However, one of the principal changes will be that we are opening up the second floor of the original mansion. Those are the private family rooms; the bedrooms, breakfast room, studies, and spaces like that, which are smaller scale than the rooms downstairs.”

“It will give us about 25% more space to show our collection. That is a big factor because our collection has continued to grow over the years, and more and more things have been going into storage. Once we move back, we’ll be able to bring out the collection more.

“Right now, what we’re thinking through is what objects will work better in the more intimate rooms upstairs. For instance, we ended up putting all our early Italian Renaissance pictures in one small gallery on the third floor here at Frick Madison. They’re very powerful in that small room. There are some rooms on the second floor of the mansion that have roughly those dimensions. So, that’s the kind of thing we’re thinking about doing when we move back up there.

“We’ve also been very fortunate to receive some gifts and private collections, which we’ll be integrating into the new space.”

A revamped mansion

In addition, the renovated Frick Collection building will have, for the first time in its history, a dedicated special exhibition space.

“We had a space before, but it wasn’t designed correctly, it was initially designed as seminar rooms,” explains Wardropper. “For example, it had very low ceilings, which meant that we couldn’t put paintings in those galleries.”

“We’ll also have an education centre which we’ve never had before. We will be making some changes to the library to improve its capacity to deal with digital work. Plus, we’ll have a new auditorium that will be larger and have better acoustics.

“We’ll also be addressing the infrastructure. It’s an opportunity to redo all the skylights and the electrical system, which hasn’t really changed since 1935, to put in whole new heating and air conditioning systems. This is all important for the future preservation of the collection.”

Engaging new visitors

A key area of work for The Frick Collection, like for many other museums, is how to reach and connect with a wider audience.

“One of the issues that we face, more and more pressingly, is trying to do a better job reaching our audience, determining what our audience is and trying to reach a wider audience,” says Wardropper. “How do we reach a younger, more diverse audience that doesn’t think the Frick is for them?”

“It’s not just our problem, I think it’s an issue for museums generally. But it’s a specific concern for us because we are an old master institution in a society that’s paying less and less attention to that aspect of history.

“One of the ways to do it is to have inventive programming that allows people to take an interest in what is on our walls and to try to begin to see themselves there. Our paintings are mostly of white people of European extraction. That’s pretty limiting. But are there ways in which we can talk about what’s not there and why they’re not images of other people.”

Connecting with a wider audience

An example of this kind of programming is Frick Film Project, a collaboration between The Frick Collection and the Ghetto Film School, a Bronx-based independent film organisation.

“For this programme, now in its seventh or eighth year, we work with an organisation that teaches high school kids how to make films. They come into the Frick and over the course of a year they learn about our pictures. Then they make a film inspired by something that’s here.

“A lot of these kids have never been inside of a space like ours. We can reach these kids and show them that old masters had a way of telling a story through a painting and that this might be useful to them when they come to make their own films and tell their stories. That shows how we can come up with creative ways to engage people. It’s one of my favourite programmes that we do.”

“We’ve also hired a new head of education, April Kim Tonin. She’s got a two-year runway to prepare for returning so we’re having intensive conversations about how what audiences we want to reach and how we can reach them.

“I don’t have all the answers yet. But it’s what’s nice about the time that we’re in here is it’s kind of an experimental period; we’re out of our permanent building and we have fewer strictures on us than we might normally. This means that we can try things out, to see what works and what we can move back with us.”

New voices at Frick Madison

Another example of the museum’s efforts to reach a more diverse audience is its recent series, Living Histories: Queer Views and Old Masters.

“That was an idea of the curators, and it was born from the fact that we are, exceptionally in our history, currently lending some of the pictures that Henry Clay Frick bought. When they go out, it occurred to the curators, that we could invite younger contemporary artists to make pictures in response to the missing pictures and the pictures that are still there.

“So, this series has been a pop-up that we have run when something goes out. For instance, we sent a Vermeer to an exhibition in Dresden, and an artist named Salman Toor did a painting called Museum Boys, in response to the Vermeers that were there. We also had a painting by Jenna Gribbon hanging between our two portraits by Holbein, breaking up the pairing of Thomas More and Thomas Cromwell.”

“Finally, we’ve sent off our Rembrandt Polish Rider to Poland and a Nigerian-born artist, Toyin Ojih Odutola has created to hang face to face with the Rembrandt Self-Portrait that remains in the same gallery. It’s an interesting kind of dialogue that we’re setting up.

“We also have a series of books called the Frick Diptych series. In this, we invite contemporary artists and writers to put forward a response to an artist. They are small books about a single work of art, and they feature people like William Kentridge, Olafur Eliasson, Alan Hollinghurst, and Hilary Mantel, writing a response to a classic art historical essay.

“That’s been another successful dialogue that we have underway.”

Museums evolve post-COVID

Talking about the main challenges that the museum sector faces going forward, particularly in the wake of the pandemic, Wardropper says:

“I think we’re starting to learn how to live with COVID and it’s clearly had an impact. But it’s not the only factor to consider as we look to the future. There’s been a lot of other factors, both in this country and abroad, and a lot of it has to do with social justice and the very real need to bring greater diversity at every level to institutions like museums.”

“We’ve been relatively fortunate economically, as we’d already downsized before our move to this building. So, we didn’t have kind of the dramatic financial reversal that a lot of other institutions have had during the pandemic. But I think these financial constraints have forced institutions to look at themselves again more closely. The situation is causing us to think about the purpose of museums and what we are doing today.

“There’s certainly more energy put into the audience now. Museums are thinking about what the audience is interested in and how we make the community feel that we are part of them. The solutions are many and I think they vary from institution to institution. A museum should be designed to try to work in whatever the particularities of their community are.”

The power of art

“The Frick is a small, Manhattan-based institution, but we have an internationally recognised collection and programme,” he continues. “So, how can we be both a local museum and an international one?”

“Our weekly video series Cocktails with a Curator was a phenomenal success; we’ve had 1.7 million views of 65 episodes. That came out of nowhere after the pandemic hit.”

“This idea of something very personal and short and with a fun twist, it captured people’s imaginations. It also poses a challenge; how do we keep that going? Should we keep it going? How do we cater to both in-person and digital guests? Can we do both? Can we live stream everything? Or are some things just better in one format or the other?

“These are all just some of the questions which we’re grappling with now. And which a lot of other museums are grappling with too. But mostly I think there’s just a pent-up desire for people to see one another, and to see art. It’s something which I hope we don’t forget as we move past the pandemic, that the arts really can play a role in addressing our social needs.

“We shouldn’t forget the power that art has to do good and to inspire people.”

Looking ahead

Finally, on his hopes for the future of The Frick Collection, Wardropper says:

“The whole team has been working for years to make this renovation a reality. I think that, when it’s finished, the institution will have a renewed sense of its mission.

“I want to keep that balance between being a small intimate space and being one that now has greater resources to do the things that it wants to do. Whether that may be exhibitions or other kinds of public programming.”

“Exhibitions in the field of Old Masters have become rarer and rarer. So, I’m very proud of the fact that the Frick has continued to develop better and better exhibitions. For example, one of our exhibitions, on an 18th-century Italian decorative artist and designer named Luigi Valadier, was named Exhibition of the Year by Apollo magazine in 2019. To be able to mount an exhibition at that level of quality was really rewarding.

“The Frick Collection has created a niche for itself of relatively small exhibitions that are very well focused in a field that is not receiving as much attention these days as it did 20 years ago. With the new facilities, we will be working to continue that, in order to enrich the audience’s knowledge about the permanent collection. I’m proud of what we’ve done in the past and I hope we’ll be able to continue that in the future.”

Top image: Four grand panels of Fragonard’s series The Progress of Love are shown together at Frick Madison in a gallery illuminated by one of Marcel Breuer’s trapezoidal windows. This view shows two of the 1771 – 72 paintings, with two later overdoors visible in the next gallery. Image credit Joe Coscia.