The event features hundreds of exhibitors displaying the newest rides and technologies, complemented by a strong schedule of educational programmes and networking events that foster peer learning and strategic discussions.

IAAPA, the International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions, says that the show will feature over 1,100 exhibitors, more than 170 educational sessions, and numerous opportunities to foster meaningful connections.

This year, the event will highlight industry excellence and storytelling.

Legends: A Hall of Fame Celebratory Affair is returning on 17 November to honour five industry leaders, including entertainers and operational innovators, while the Leadership Breakfast features Mark Woodbury, chairman & CEO of Universal Destinations & Experiences, as the keynote speaker.

Following a successful debut last year, the Haunting Grounds fair returns, showcasing Halloween attractions and seasonal experiences.

For operators and suppliers seeking new opportunities, the event continues to serve as a comprehensive hub: featuring immersive VR and motion simulators, water solutions, POS technology, F&B trends, and health & safety innovations.

Special events at IAAPA Expo 2025

On Sunday16 November, those arriving early can participate in ticketed EDUTours of Royal Caribbean's newest Icon Class ship, Star of the Seas, or Fun Spot America.

More special and ticketed events take place on Monday, including a Lunch and Learn featuring Walt Disney Engineering, as well as receptions for the zoo and aquarium community, food and beverage operators, water park operators, FECs, and museum and science centres.

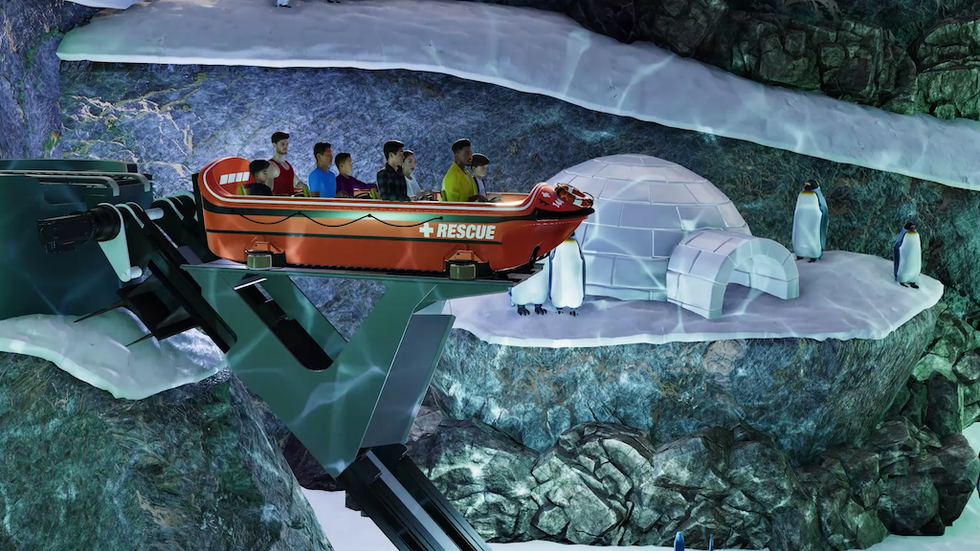

Tuesday 18 November sees an EDUTour to SeaWorld Orlando, taking in Penguin Trek and Expedition Odyssey, and a chance to go behind the scenes at Universal's Halloween Horror Nights. There is also an FEC Lunch, the Latin America and Caribbean Lunch and Learn, and the Women in the Industry Networking Lunch.

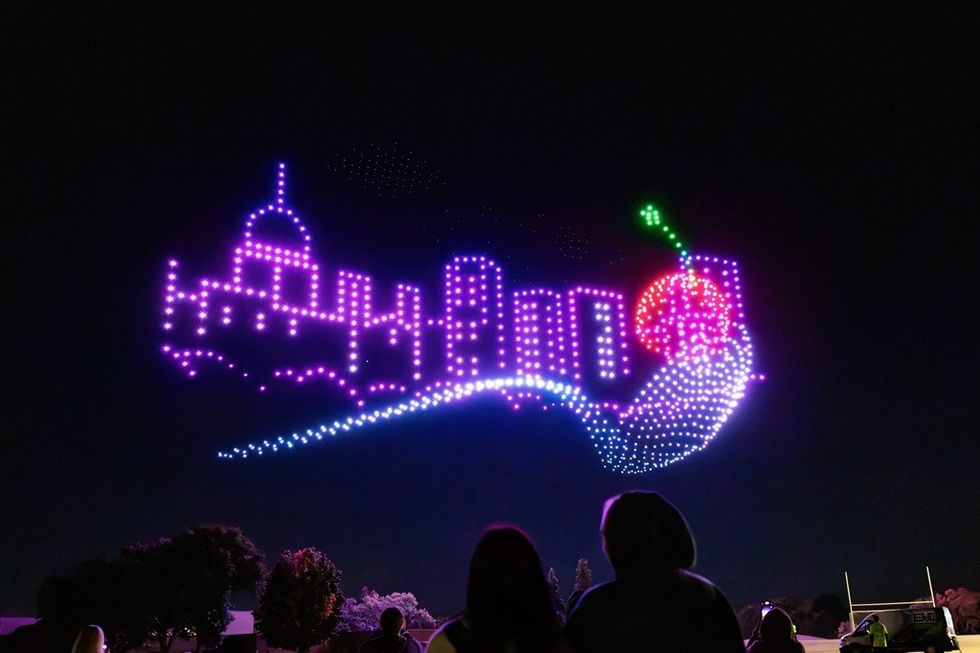

The opening reception will take place in the evening, as well as an all-new drone show and the young professionals reception.

On Wednesday 19 November, special events include the Influencer Breakfast, sponsored by Triotech. Lunchtime events comprise the Amusement Parks and Attractions Constituency Lunch, the FEC Lunch, and the Water Park Operators Lunch and Learn.

In the evening, the carnival and showmen's reception will take place, alongside the natural and adventure attractions reception, the water park social, the Latin America Fiesta, and the EMEA reception.

Another EDUTour takes place on Thursday 20 November, to Legoland Florida. Elsewhere, the Asia Pacific, Brazilian and Canadian Breakfasts are also scheduled.

Those with tickets will be able to explore Universal Epic Universe in the evening, as part of the exclusive IAAPA Celebrates event.

Education sessions: highlights from the agenda

Monday 17 November

On Monday morning, Gen Alpha’s Great Expectations: Experience Building for a New Generation will examine how attractions can create future-ready experiences aligned with Gen Alpha’s values, emphasising key trends and practical approaches to meet the expectations of this influential new audience.

Speakers include Christopher Arnold of Fred Rogers Productions, Matt Dawson from RWS Global, and Julie Moskalyk of Supply + Demand Studio.

Another interesting EDUSession will be Revitalizing the Storytelling Edge in Attractions.

Chaz Moneypenny of the University of Central Florida, Emma Oliver of Emma Oliver Creative, Dominique Marmolejo from The Walt Disney Company, Charlie Jicha of THG Creative and Jared Wells of JDWstories will share how diverse attractions use storytelling to enhance guest experiences.

In Zoos and Aquariums, a Global Perspective, speakers will share long-term research findings and real-world insights from a Libéma manager, offering valuable lessons for zoos worldwide, navigating evolving societal expectations and competitive landscapes.

This features Jason Jacobs from Lion Country Safari, Goof Lukken from Breda University, David Rosenberg of SSA Ventures, and Melissa Felder of Curiodyssey.

The Rise of Gaming IPs in Attractions: An Economist View, with Natalia Bakhlina of Leisure Development Partners, will explore the economic factors behind the rise of gaming IPs in attractions, contrasting opportunities with challenges of integrating digital into physical spaces, and look at what this trend means for developers, investors and designers.

Weather and work-life balance

Then, Anthony Woodson of ZooTampa at Lowry Park, Emily O'Hara from Detroit Zoological Society, Jessica Hintz of Phoenix Zoo, and Ali Rubinstein of Walt Disney Imagineering will present Weathering the Storm of Extreme Weather Events.

This session discusses how new facility planning, master planning, and operational changes for venues can build resilience and flexibility against unpredictable weather, maintaining attendance and revenue long-term.

In the afternoon, in Shared Balance: Work-Life Integration in the Attractions Industry, panellists share insights, strategies, and wins demonstrating that work-life integration is possible even in busy environments.

Speakers include Steven Tarca of SUMMIT One Vanderbilt, Clara Rice from Adirondack Studios, Dawn Foote from Katapult, Jeff Alexander of Holiday World & Splashin' Safari, and David Gray from Lagoon Amusement Park.

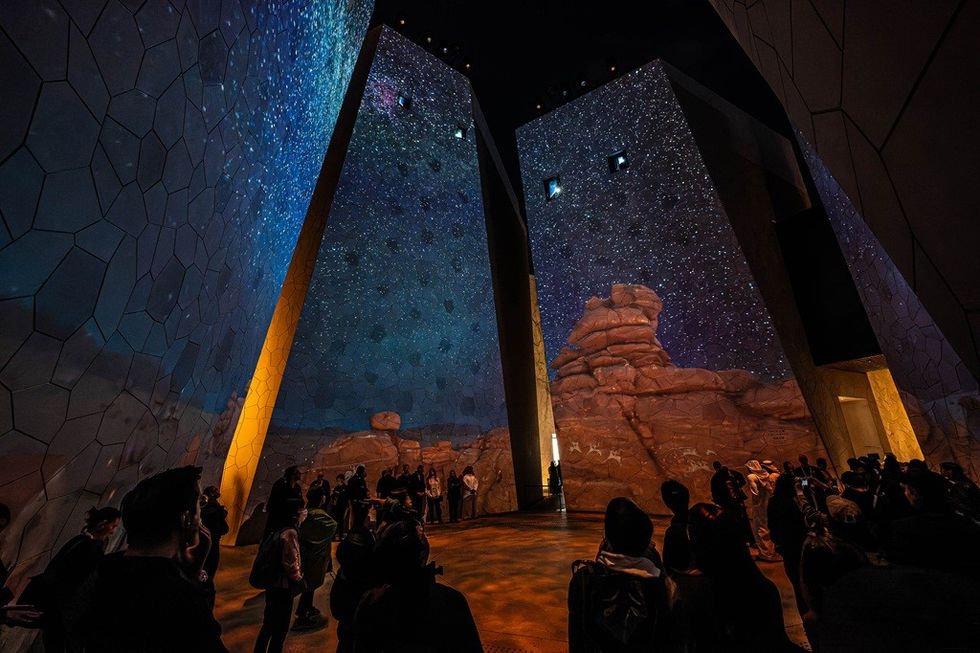

Reimagining Heritage Tourism: How Immersive Experiences Drive Engagement features insights from Moment Factory's Manon McHugh. This EDUSession examines how immersive multimedia can transform historical attractions and maintain heritage sites' relevance in modern tourism.

Beyond the Guidelines: Strengthening Safety Culture is a Collective Commitment emphasises that safety isn’t just a department, checklist, or protocol—it’s a top-down commitment practised by all.

Mobaro's David Bromilow is joined by Jason Freeman of Six Flags, Gina Claassen from Herschend, Mike Denninger from Denninger Development LLC, and Luisa Fernanda Velasquez from Parque Del Cafe, sharing practical ways to make the industry safer.

Trends, tech, and new tools

In The Winning Formula: Combining Creativity & Data to Craft Scalable Immersive Experiences, panellists will discuss how collaborations between creators and technology innovators are driving industry growth and transforming the future of live and immersive experiences.

The speakers will be Jeff Wyatt from Space Center Houston, Mariano Otero of Fever, David Woody from Griffin Museum of Science and Industry, and Corey Breton of Cosm.

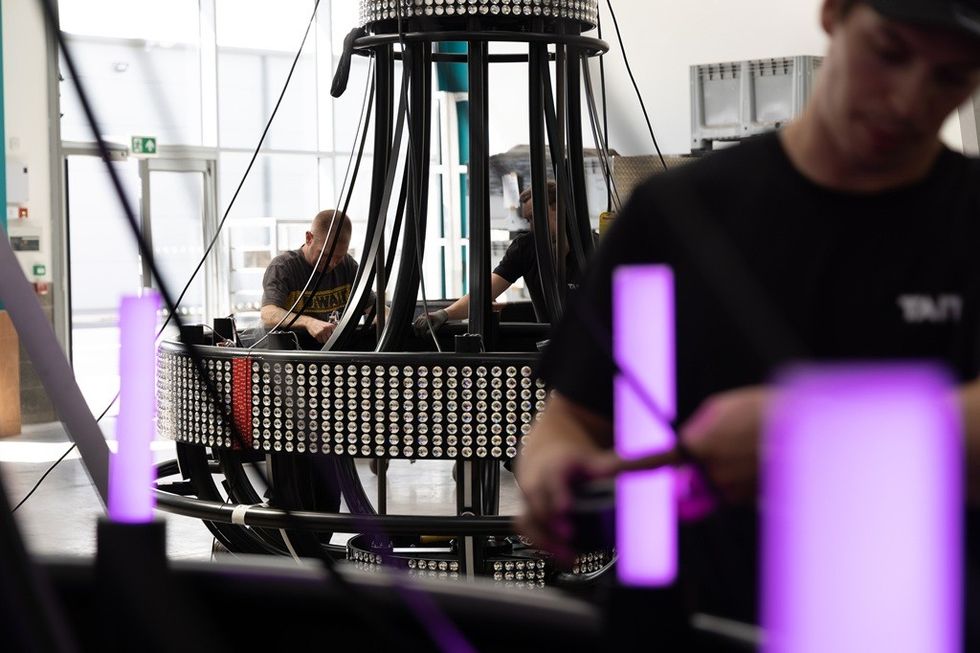

Emerging Trends, Techniques and Technologies in Experiential Design explores how emerging technologies and storytelling shape unforgettable guest experiences. This EDUSession is led by TAIT's Cynthia Sharpe and Imagine's Shawn McCoy.

Later, in The ROI of Competitive Socializing: Driving Revenue Through Innovation, attendees will learn how venues use competitive socialising to increase dwell time, boost secondary spends, and deliver measurable ROI, presented by Ade Jones of CONDUCTR.

ProSlide moderates Unlocking the Potential of Water Park Operations After Dark, featuring Mitch Petty of ProSlide, Justin Brown from American Resort Management, RAC Carroll of Jeff Ellis & Associates and Anthony Sabo of Zoombezi Bay.

This session explores the growing momentum behind nighttime water park operations and the design, safety, and guest-experience strategies driving new hours of revenue, capacity, and excitement.

Finally, Louis Alfieri of Raven Sun Creative will present AI Unleashed: Redefining the Entertainment Ecosystem, examining how AI is transforming concept development, production, and creative values. Attendees will learn to seize opportunities amid disruption, striking a balance between innovation and integrity in a challenging, ethically complex market.

Tuesday 18 November

One of the first EDUSessions on Tuesday morning is Designing for Every Mind: Creativity, Inclusion, and the Guest Experience. This looks at how inclusive practices, grounded in understanding cultural perspectives, guest motivations, and neurodiverse needs, can foster memorable experiences for guests.

Speakers include Meredith Tekin of IBCCES, Jenny Lim from Gigantic Playground, Genein Letford of CAFFE Strategies, Inc., Ned Diestelkamp from PGAV Destinations, and Julie Estrada from Merlin Entertainments.

Another early session is The Future of Experiential Cruise Destinations with Josh Martin of Martin Aquatic, Keith Carr from Carnival Cruise Line, Leon Camarda of Project Management Advisors, Inc., and Scott LaMont of EDSA.

They discuss upcoming cruising plans, especially after Carnival’s Celebration Key debut in the Bahamas this summer. The panel shares how owned islands exceed guest expectations and how immersive design offers a unique vacation experience beyond ports.

In Beyond the Story: Crafting the Future of Location-Based Entertainment, award-winning storyteller and creative director Margaret Chandra Kerrison invites attendees to learn more about how the future of LBE is being shaped by diverse perspectives, authentic storytelling, and bold innovation.

Later, Myke Eggers of SSA Group will present Case Study: Learn from SSA on the Hospitality Initiative / Mirror Check: Is Your Hospitality Strategy Polished? SSA launched bold initiatives in 2025 to improve hospitality through better training and engagement. Join this session to hear its wins, challenges, and overall impact.

Immersivity and accessibility

On Tuesday afternoon, TAIT's Arielle Lindsey will present Creating Immersion through Atmosphere Entertainment with colleagues Jim Shumway and Erica McCay alongside Ameenah Kaplan of Walt Disney Live Entertainment and Andy Crocker from Mister & Mischief.

They will discuss how atmosphere entertainment, such as roving performers, ambient characters and sounds, in-world interactions, immersive media moments, engagement, and sensory design, can alter both a space and the guest experience.

Attendees can also attend the annual IDEA Roundtable in the afternoon. This session, through multiple rounds of questions, aims to foster an open discussion and provide attendees with the opportunity to discover new, innovative methods for supporting this important initiative.

In Predictive Modeling for Optimized Guest Experiences in Immersive Design, moderated by Michael Libby of Worldbuildr, panellists will explore how forecasting guest flow, testing operational scenarios, and simulating interactions early in design can create more engaging, resilient, and profitable destinations.

Speakers include Ann Morrow Johnson of Gensler, Michael Tschanz of Tschanz Technologies, and Amanda Clay from Meow Wolf.

Tuesday's Solution Spotlights

Several Solution Spotlight sessions will also take place throughout the week. Tuesday's spotlights not to miss include Gateway Ticketing Systems, Inc. – Inside the Innovation: Exploring Gateway’s Latest Features and Future Roadmap.

Explore Gateway’s latest products and features in this 20-minute session with Zach Yusypchuk. He highlights how the enhancements streamline operations, improve integrations, and add value to a Galaxy investment, and shares an exclusive look at the product roadmap.

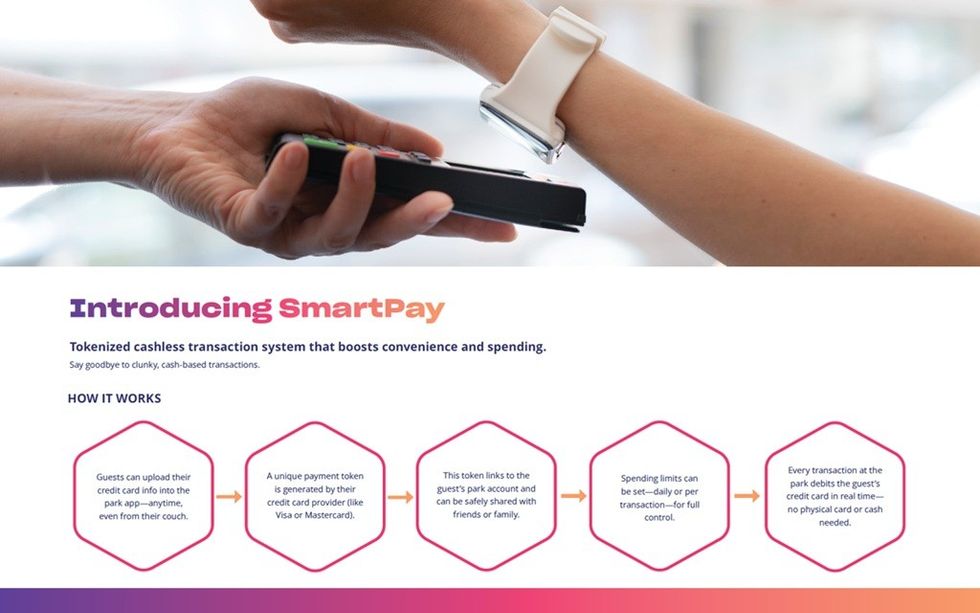

In accesso – Payments Without Limits: The Future of Guest Transactions, delegates can see how modern partnerships and integration architecture help operators create flexible, feature-rich payment experiences.

Using accessoPay 3.0, Michael Wiggins will show how payment innovation helps venues stay ahead of retail trends and generate new revenue.

Wednesday 19 November

One session to watch on Wednesday morning is Beyond POP (Pay-One-Price): How Theme Parks innovate Revenue Streams beyond Physical Expansion.

This examines how the attractions sector, especially theme parks, is adopting new pricing and revenue strategies. Speakers include Marie Weissbach of WhiteWater and Peter Gruetzner from Therme Erding.

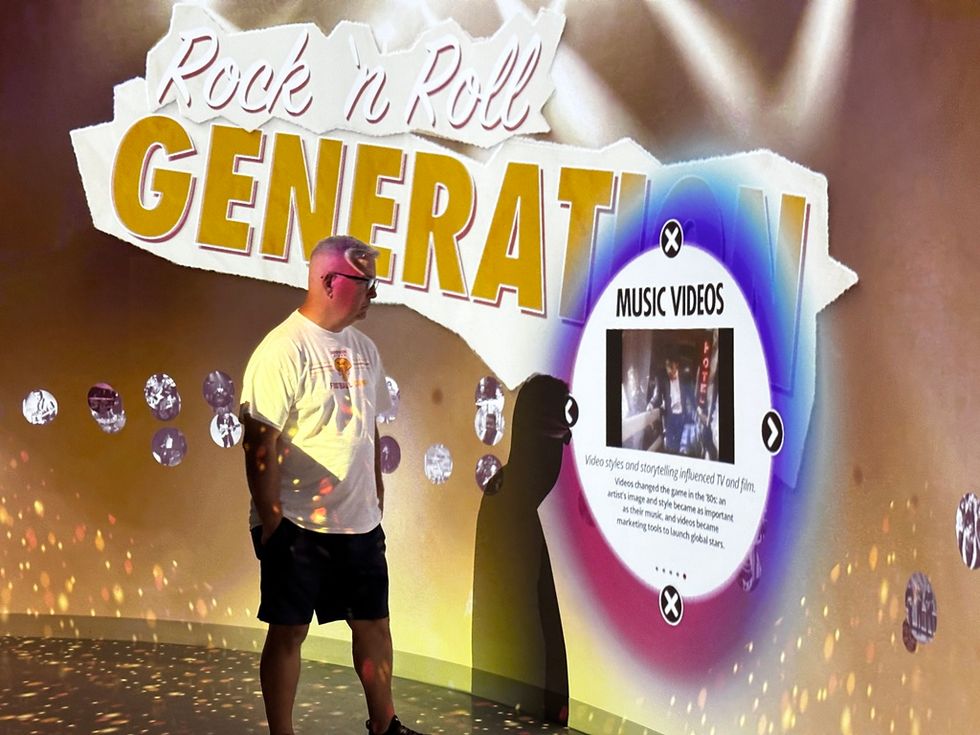

How to Capture SuperFans: Designing Deeply Transformative Experiences will illustrate how to create immersive and transformative experiences that profoundly connect with visitors seeking more than just entertainment at amusement parks, attractions, and museums.

The panellists are Meghan Gardner of Guardian Adventures, Jasmin Jodry from MOTO, and Caro Murphy of Incantrix Productions

Later that morning, The Terrifying Leadership Experience encourages participants to develop practical, real-world skills in a psychologically safe (yet deliberately challenging) environment.

From managing conflict to providing feedback, they will build the confidence to approach any difficult conversation with composure.

Speakers include Scott Swenson of Scott Swenson Creative Development, Matt Heller of Performance Optimist Consulting, and Heather Doggett from Scream Score/Immerse Universe.

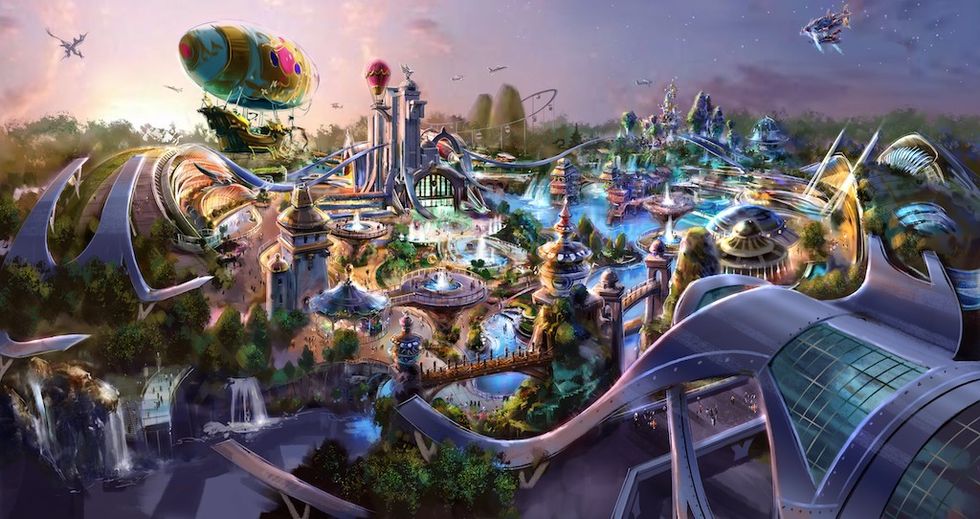

In the afternoon, the annual Legends Panel is back, this time entitled Legends of Epic – The Creators of Universal Epic Universe, in which attendees can discover the valuable lessons, tools and strategies that created Universal Epic Universe.

Moderated by Bob Rogers of BRC Imagination Arts, Eric Parr, Jody Keller, Katy Pacitti, and Steve Blum of Universal Creative share insights, strategies, and lessons of a lifetime.

Wednesday's Solution Spotlights

Highlights from today's Solution Spotlights include Hasbro – PEPPA PIG and the Magic of Play: Turning Stories Into Experiences, presented by Matthew Proulx of Hasbro, Inc.

He explains how Baby Evie, the newest member of the family, sparked a series of creative initiatives that translate storytelling into real-world activities. Attendees will also have an exclusive preview of upcoming Peppa Pig experiences.

Brogent Technologies Inc. – Flight Reimagined: Breakthrough Concepts in Next-Gen Attractions invites delegates to step into the future of attractions with the company's next-generation flying theatre, presented by Stefan Rothaug.

In ROLLER – 2026 Benchmarks Revealed: The Intelligence Playbook for Attractions, Brett Sheridan will unveil exclusive insights showing how venues stacks up, where growth opportunities lie, and the playbook to boost efficiency, loyalty, and revenue in the year ahead.

Then, in DOF Robotics – The Rise of Edutainment: Blending Immersion and Education in the Next Gen of Attractions, Mirsat Satis will explain edutainment, its effectiveness, current thriving areas, and technology's role. He'll also discuss how DOF Robotics uses edutainment in products and its future vision.

Storyland Studios, Inc. – The Secret Sauce Recipe for Success in Experiences will be presented by Mel McGowan, founder and CCO of Storyland Studios.

He reveals the timeless recipe for creating impactful and profitable experiences. Using strategic, spatial, and interactive storytelling, attendees will learn to develop destinations that unite people and leave a lasting impact.

Thursday 20 November

Thursday morning begins with a regional exploration of trends in The EMEA Attractions Market: Trends, Practices, and What Sets It Apart. This offers an overview of the EMEA market, focusing on how attractions develop with operations and partnerships that differ from US practices.

Speakers include Bart Dohmen of TDAC BV, Lukas Metzger from Europa-Park, Andy Hygate from Pleasure Beach Resort, and Annabel Rochfort of Rochforts LBE Consultancy.

In Engaging Brand Experiences: The Art of Turning Brands into Destinations, the panel will examine how renowned brands such as Bass Pro Shops, National Geographic, and Delta Air Lines craft transformative guest experiences that build loyalty, increase engagement, connect with employees, and boost revenue.

Exhibit at Delta Flight Museum courtesy of Rank Studios for Delta Flight Museum

Exhibit at Delta Flight Museum courtesy of Rank Studios for Delta Flight Museum

The panel includes Shawn McCoy of Imagine, Nedra Wilson from Minecraft/Microsoft Gaming, Anthony Hickson of Imagination Immersive Studio, Rochelle Wilhelm from the National Geographic Society, and Nina Thomas of Delta Flight Museum.

Later in the morning, Interviewing 102: Presenting Yourself Authentically offers expert guidance on effectively presenting yourself, what employers want to hear, and what to avoid.

PGAV's Dave Cooperstein shares his expertise alongside industry veterans Nicola Rossini of ADKS and Joe Garlington from the University of Southern California.

Driving Social and Environmental Impact Through Responsible Sourcing talks about how attractions can leverage their purchasing power and industry influence to create meaningful change by integrating sustainability into their supply chains.

Speakers include Andrew Fischer of SSA Group, Colley Hodges from Houston Zoo, and Veronica Celis Vergara from Valumia.

Empowerment and collaboration

Empowering Water Park Women in Leadership: Continuing the Conversation sees panellists sharing their experiences, challenges, and the opportunities that come with leadership roles.

This session, part of an ongoing series that highlights the incredible women shaping the industry year after year, features insights from Franceen Gonzales of Avante International, Una de Boer of WhiteWater, Marah Rodriguez from Mobaro, Denise Beckson of Morey's Piers, and Neva Heaston of Royal Caribbean.

Participants will learn how embedding sustainability can improve efficiency and deliver long-term value across their organisation in Making it Core: Embedding Sustainability as a Strategic Value Driver.

Speakers include WhiteWater's Una de Boer and Liseberg's Andreas Andersen.

In The Awesome Scary Future of AI, speakers will showcase current data on the variety of AI tools available today, including AI-driven apps, virtual avatars, and operational systems aimed at enhancing efficiency and engagement.

This session, featuring LDP's Yael Coifman, David Andrade of Theory Studios, Hind Galadari of Warner Bros. World Abu Dhabi, and Jacob Trevino from Gorilla Cinema Presents, will provide insights into how AI is being developed into useful tools across operations, guest services, and creative offerings.

Later in the afternoon, The Magic of Collaboration - How Warner Bros. & Universal Parks Bring Harry Potter to Life will unveil the teamwork involved in creating spectacular experiences and using live entertainment to enhance storytelling.

Attendees will hear from Kathrynn DiGenova, Anisha Vyas Burgos and Gary Blumenstein of Universal Creative, alongside Hope Glomski from Warner Bros. Discovery Global Experiences, and Carlos Avilas from Warner Bros. Discovery.

Thursday's Solution Spotlights

More Solution Spotlight highlights include Redefining Immersive Media with TAIT. Corin Watson and Eric Hoff discuss the company's unique approach to storytelling through media, examining how technology, connection, and engagement are redefining what it means to be immersive.

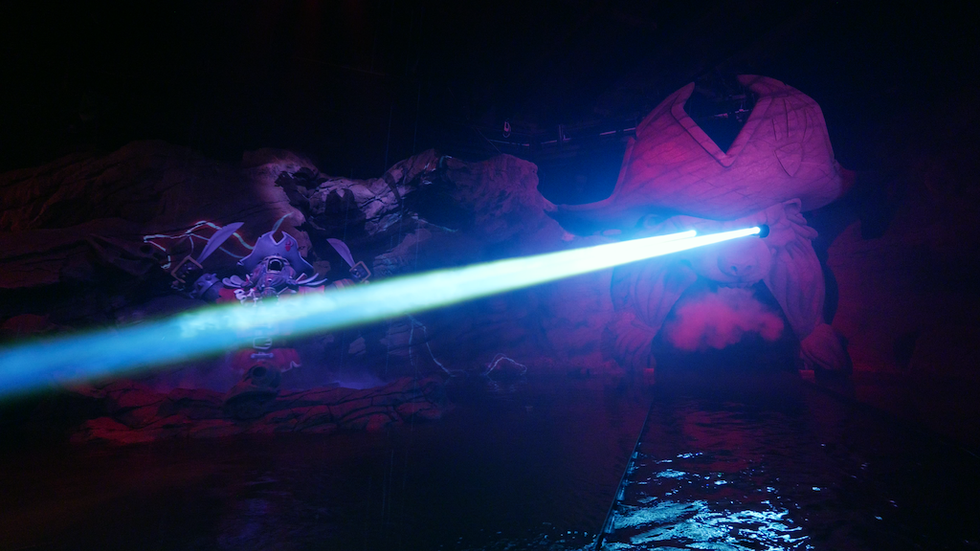

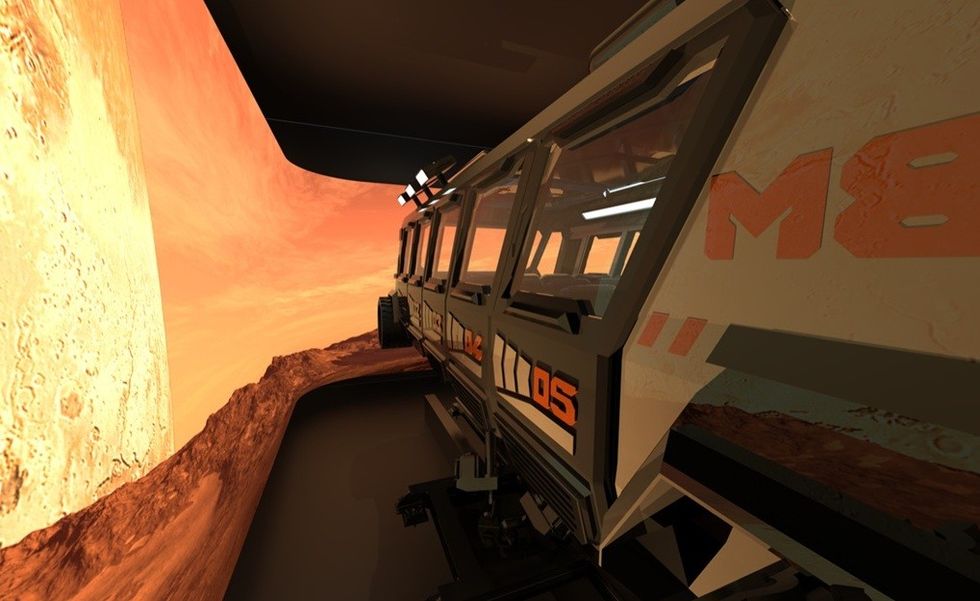

Simtec Systems: One Ride Infinite Worlds - New VR-based dark ride attractions will highlight a new kind of dark ride attraction that combines a hyper-reality VR platform with cutting-edge motion-based ride technology, presented by Mike Haimson.

Exhibitors not to miss at IAAPA Expo 2025

accesso - booth #5131

accesso Technology Group PLC, a leading technology provider for attractions worldwide, will present its connected solutions at IAAPA Expo 2025.

Visitors to the booth can learn how these streamline operations and drive revenue across ticketing, food and beverage, virtual queuing, mobile apps, and distribution. The team will offer hands-on demos of accesso Freedom, including mobile ordering and operational workflows.

Operators are making vital digital choices across ticketing, e-commerce, apps, and in-park activities, and accesso supports them in making quick and confident decisions.

Whether deploying robust built-in features or customising solutions to meet specific needs, the firm's goal is to deliver measurable business results and create a guest experience that fosters repeat visits.

As detailed above, the team will also present a Solution Spotlight on the future of guest transactions.

To schedule a meeting, attendees can get in touch by email.

Alterface - booth #862

Alterface, a leader in interactive technology, will announce its contribution to the new interactive dark ride set to debut at Parc Astérix in 2028.

With decades of expertise in interactive design, gameplay dynamics, and guest behaviours, Alterface brings its know-how to this ambitious new family attraction.

Fun, highly intuitive, and accessible to all audiences, the attraction captures the unmistakable humour and spirit of the Astérix universe. Featuring six interactive scenes and four-seater vehicles, the ride will deliver a smooth, high-capacity interactive experience.

Guests will use their magic potion flasks to compete in a series of playful, carnival-style challenges inspired by Gaulish mischief and British eccentricity.

The ride adopts a joyful, chaotic, and energetic tone, filled with gags and anachronisms characteristic of the comic book.

The team's appearance at IAAPA Expo 2025 follows a successful visit to IAAPA Expo Europe in September, where the company won several awards.

Stéphane Battaille, CEO; Laurence Beckers, creative director; Etienne Sainton, product manager; and Mattheis Carley, partnerships director, will attend. Meetings can be booked via email.

Booking meetings: sales@alterface.com

Alvarado dormakaba Group - booth #4647

Alvarado dormakaba Group, a leader in access control and guest flow solutions trusted by attractions, cultural institutions, and entertainment destinations worldwide, will announce its newest direct API integrations with accesso Passport, AXS and SimpleTix.

The firm now supports more than three dozen seamless integrations with leading ticketing providers worldwide, enabling attraction venues to deploy its diverse portfolio of guest self-scanning intelligent admissions devices.

The team at the booth includes Brian McNeill, vertical business owner, sports and entertainment; Matt Ulery, sales manager for attractions; Jackie Purcell, sales manager for sports and performing arts; and Leonardo Collino, business developer for EMEA.

Attendees can get in touch by email.

Alvarado dormakaba Group recently shared how its UltraQ-AMT admission turnstile is improving operations and the guest experience at Moonshine Mountain Coaster in Gatlinburg, Tennessee.

It has also streamlined guest access at Somersplash Waterpark in Somerset, Kentucky.

AOA

AOA, a leading immersive experience design, production, and project management company now in its 16th year, continues to bring imagination to life through immersive design, fabrication, and delivery for destinations worldwide.

Recent highlights include large-scale cultural attractions, live experiential installations, and branded storytelling projects with partners such as MOTE SEA Aquarium, Her Universe Fashion Show, Niagara Takes Flight, and the Milken Center for Advancing the American Dream.

The firm also expanded its creative leadership and associates, deepening AOA’s expertise in live and experiential entertainment, museums, conservation and environmental storytelling, and location-based entertainment.

With more than 150 projects opened across six continents, AOA remains focused on creating experiences that move people.

Attendees can book meetings with Denise Hatcher, managing director, and Oksana Wall, VP of strategic engineering, by email.

AStation - booth #7060

AStation will be giving free Enterverse demonstrations throughout IAAPA, showcasing its proprietary technology.

Amid the many booths, people will see a multiverse of characters and sights to interact with. And because it is AStation, it will be outside, free roaming, and on the industry-leading Apple Vision Pro headsets.

AStation revolutionises entertainment by blending virtual content with reality in real-time.

The company uses cutting-edge Apple Vision Pro headsets and six geo-sensing cameras.AStation’s proprietary technology, called Enterverse, transforms massive outdoor spaces into immersive mixed reality playgrounds.

Its flagship location in Beijing features two Enterverse experiences. Shan hai Space is an interactive adventure featuring mythical creatures and ancient ruins throughout alleyways, cafes, and promenades. Dinosaur Park transports visitors back to the Jurassic era.

IAAPA Expo is AStation's first appearance in the attractions industry. On Wednesday 19 November at 11:15 am, it will be making a global announcement at the booth.

Attractions.io - booth #4247

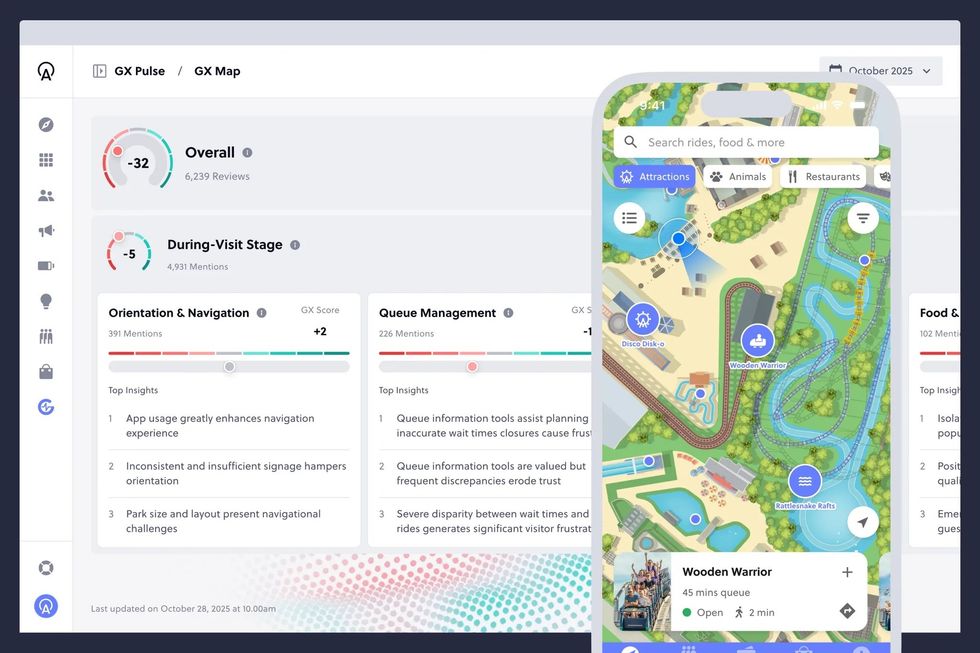

Attractions.io, a leading creator of mobile visitor apps, will also exhibit. It is the mobile app platform that connects every stage of the guest journey, from ticketing and navigation to food ordering and feedback, helping operators deliver personalised experiences that influence on-site spending, and boost NPS.

Trusted by more than 150 world-class venues, including Six Flags, Merlin Entertainments, Kennedy Space Center, and San Diego Zoo, Attractions.io empowers operators to deliver seamless, connected experiences that guests love.

At IAAPA Expo Orlando, the team will demonstrate how its technology brings digital and in-park experiences together to unlock the full potential of every visit.

Alongside the mobile app platform, attendees can explore MapLayr, Attractions.io’s standalone maps and wayfinding SDK, which provides reliable blue-dot positioning and GPS routing, enabling digital teams to bring intuitive, location-aware navigation to their existing mobile or web apps.

Visitors will also get an exclusive first look at GX Pulse, a new AI-powered guest intelligence tool that consolidates review and survey data from multiple sources, maps feedback trends across the guest journey, scores them and provides data-driven recommendations to improve satisfaction and operational performance.

Attendees can meet Mark Locker, founder & CEO; Jacob Thompson, director of customer experience; Peter O'Dare, VP of product; and Cory Nadler, senior customer success manager. Meetings can be booked here.

Axess - booth #5440

Axess, a leading provider of ticketing and access management solutions for the visitor attractions industry, will showcase the new to market Axess SMART GATE 600 with Flap Glass and Axess SMART GATE 600 with Axess TURNSTILE 600 on Axess SMG MOBILE PALLET with Battery, WiFi and Axess SUITE READER 600.

Visitors to the booth can also discover the Axess ARENA POST 600 and Axess SMART POST 600 - Jäger Edition.

Oliver Suter, CEO; Christian Müller, head of business unit attractions; Rob Clark, managing director of product and growth for North America; Tim Larsen, SVP of resort solutions; and Renier Steyn, managing director, will all attend. Meetings can be arranged via email.

Earlier this year, Axess shared how it is shaping the way millions of guests experience theme parks, zoos, surf parks and more with its cutting-edge access terminals and fully integrated systems.

Base Xperiential

BASE Xperiential, a creator of holographic and immersive cinema experiences for museums, attractions and live venues, will be attending IAAPA Expo 2025.

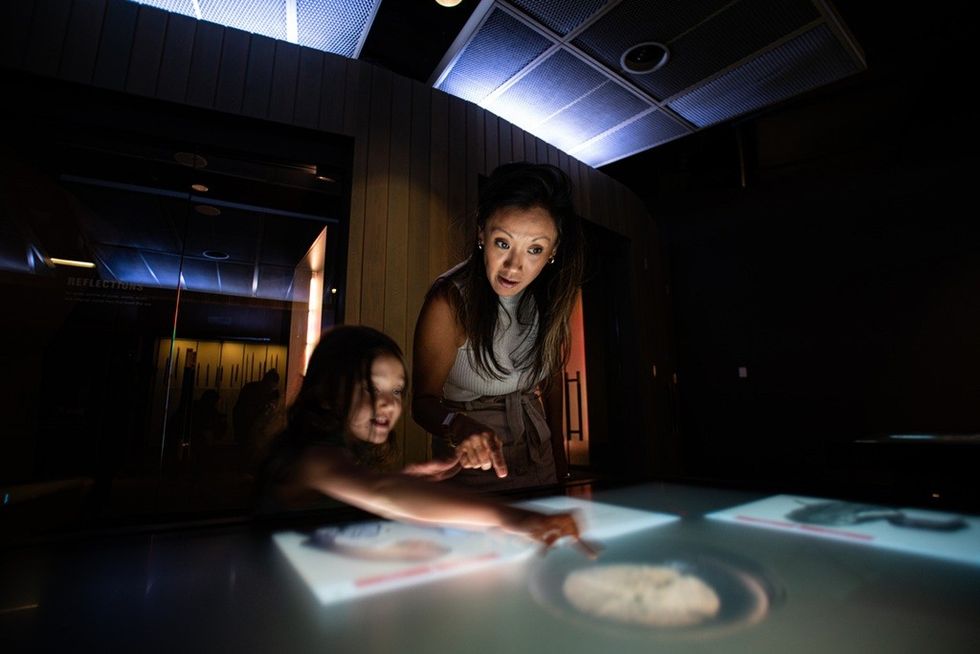

This summer, the Museum of Discovery and Science (MODS) and BASE Xperiential debuted a custom-built, freestanding HoloTheater, the first of its kind on the East Coast of the United States.

This offers an interactive learning experience that blends advanced holographic projection, panoramic visuals and spatial audio to engage and inspire audiences of all ages.

Visitors can book meetings at the show with Dan Robinson, Ryan Latham, and Dominic Roncace by sending an email. They can also witness the HoloTheater for themselves while they’re in the area, at the Museum of Discovery and Science in Fort Lauderdale.

Beaudry Interactive - booth #765

Beaudry Interactive, an experiential design and production studio specialising in themed entertainment, museums, exhibitions, live shows, and branded experiences, is also heading to IAAPA Expo 2025.

Attendees can learn how the team is pushing the boundaries of interactive design and celebrating its newest achievements as it approaches its 20-year milestone of creating experiences that connect, inspire, and delight.

The firm recently shared how it is helping clients develop distinctive, reliable, and cost-effective interactive experiences using its Adaptive Interactives framework.

Company principals David Beaudry and Valeria Beaudry will be in attendance, along with producers Nicole Graber and Danny Taylor, and director of technology Nick Taylor. To schedule a meeting with B/I ahead of the show, attendees can click here.

blooloop - booth #6138

blooloop, the leading news and networking platform for the global attractions industry, will have a booth at this year's event. The team plans to cover IAAPA Expo's press conferences, announcements, and sessions, while also reconnecting with clients and friends throughout the show.

As the most-read platform in the industry, blooloop collaborates closely with companies aiming to highlight their projects and news to the largest global audience in the attractions sector.

We would love to connect with anyone interested in boosting their company profile and discussing blooloop's opportunities. Attendees can visit our booth to say hello to the team or book meetings via email.

blooloop is also hosting a party to celebrate its 20th anniversary from 7 pm-10 pm on Tuesday 18 November, at the Sports & Social Bar, Pointe Orlando. Join us for drinks, networking and nachos. The blooloop party is free, BUT it is by invitation only as spaces are limited, so register your interest here.

A huge thank you to our Gold party sponsors, accesso, DOF Robotics, Fever and SEGA, and our Silver party sponsors, Disguise, LDP, ROLLER and Triotech. And thank you to our Photography sponsor, Photogenic.

We will also be revealing the 2025 blooloop 50 Theme Park List, in partnership with Simtec Systems, live at the event at 8 pm.

Blue Telescope

Blue Telescope, a media and design studio that creates interactive and narrative experiences, will once again sponsor the Big Break Foundation to highlight some of the industry’s most exciting new talent.

The firm will be represented by principal and managing director Trent Oliver, executive creative director Judith Zissman, and senior creative producer Dustin Stephan.

Recent highlights from Blue Telescope include the immersive preshow at the Delta Flight Museum, three remarkable media pieces for the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum, and innovative data visualisation for T-Mobile.

Connect with us at hello@bluetelescope.com

Breeze Creative - booth #1684

Breeze Creative, a creator of interactive edutainment solutions for museums, FECS, zoos, aquariums, and more, will exhibit its full suite of digital interactives, including a brand-new, never-before-seen product, Build Alive.

Kristin Barrueta, VP, will be at the booth, and attendees can book meetings here.

The company's ready-made products integrate augmented reality, motion sensors, object recognition, and interactive projection to deliver immersive, educational, and engaging experiences, all with minimal setup and quick deployment.

Popular products include the Animated Sandbox, a topographic AR sandbox with changing themes, and DrawAlive, an interactive system that animates drawings on a digital wall.

Brogent Technologies - booth #5431

Brogent Technologies Inc., a leading manufacturer of media-based attractions, will present its latest projects, including the first flying theatre in South America, which will be revealed during a press conference at the booth.

The company has seen three brand-new rides debuting worldwide this year. At IAAPA Expo 2025, it will show detailed scale models of these latest innovations and share behind-the-scenes insights into their design and creation.

Recent successes include Niagara Takes Flight, the world’s first flying theatre located alongside a world-renowned natural wonder, where Brogent provided the theme design, construction, and content creation, and Air Cruise the Ride Cruise the Ride, the first LED dome screen flying theatre, at Huis Ten Bosch in Japan.

The company was also behind ChangAn Above, the largest flying theatre in Asia, located in Xi’an, honouring the rich cultural legacy of the Tang Dynasty by blending traditional artistry with cutting-edge simulation technology.

Visitors can book time with the team via email.

Christie - booth #1060

Christie, the global visual and audio technology company, will showcase a range of technology, including MicroTiles LED and a tech preview of a new LED video wall solution, designed to elevate visual storytelling in immersive dark rides.

Sapphire 4K40-RGBH, the world’s first high-brightness hybrid RGB pure laser and laser phosphor projector, will also be on show. Sapphire sets a new standard with its exclusive Infitec colour comb 3D solution.

Unlike traditional laser phosphor projectors, Sapphire offers superior light efficiency and a wider colour gamut for brighter, more lifelike 3D experiences.

For attendees creating edge-of-your-seat attractions, captivating exhibits, or unforgettable projection-mapping spectacles, the Christie team, including Ernest Bakenie, senior director of sales, themed entertainment, and Joe Graziano, director of sales, themed entertainment, EMEA, will be on hand.

Click here to book a meeting.

Earlier this year, Christie introduced the Eclipse G3, a unique 6DLP projector that delivers true HDR for exceptional image quality.

CRYSTAL

CRYSTAL, a firm that designs and produces spectacular effects and décor for shows and events worldwidedécor for shows and events worldwide, recently delivered the UK’s first-ever water show at Drayton Manor theme park, created all water effects for Mission Bermudes at Futuroscope, and designed a striking quick sand illusion for L’Épée du Roi Arthur at Puy du Fou.

The company also produced all water effects for ECA2’s Nighttime Show at the Osaka Expo 2025, the water mirror for the Paris 2024 Olympic cauldron, and an innovative pixel fall effect for Maná’s U.S. Rock Band tour.

CRYSTAL is now preparing to unveil its cutting-edge Aqua Drones performance on the world’s largest water stage at the Dubai Burj Khalifa Fountain for the New Year’s Eve Show.

Julien Causeret, chief strategy and development officer, will be at the show and can be reached via email.

Cuningham

Cuningham, a trusted creative partner in the themed entertainment industry, will also have a presence at IAAPA Expo 2025.

For nearly forty years, Cuningham has served as a reliable partner in the sector, working with industry giants like Walt Disney Imagineering and Universal Studios to develop immersive, story-centred destinations across the globe.

From pioneering attractions to today’s next-generation experiences, the firm merges artistry, technical innovation, and storytelling to realise bold ideas. Each project reflects Cuningham’s collaborative spirit and its belief that design should both inspire and connect people through shared experiences.

With a growing presence in Orlando, which the firm recognises as the global hub of imagination and innovation for the industry, Cuningham continues to push the boundaries of experiential design, shaping destinations that engage guests, spark wonder, and endure as iconic experiences for a global audience.

For the team, IAAPA presents an opportunity to reconnect with industry partners, celebrate creativity, and explore the future of themed entertainment.

Attendees can arrange to meet Kathleen Herrington, associate principal, national market leader for themed entertainment, and office director, Orlando, by email.

Dartsee - booth #452

Dartsee, a leader in interactive social gaming, will exhibit its main Dartsee unit.

The firm recently announced the launch of Tournament mode, which is being rolled out across its devices. This new competitive game mode aims to attract larger crowds to venues, leveraging the company’s proven technology, which boasts dartboard accuracy exceeding 99%, and its catalogue of 11 unique games.

See also: How Dartsee is helping bars & entertainment venues aim high

Attendees can meet co-founders Laszo Vass and Zoltan Borsos, as well as Csilla Sárosi and Mirella Vazorka from the sales team.

Digonex - booth #4358

Digonex, an expert in dynamic pricing solutions that provide visitor attractions with customised and automated systems to drive revenue, will be on the trade show floor.

Since its founding in 2000, Digonex has been a leader in the field of dynamic pricing. Its automated and customised solutions have consistently delivered strong results across a variety of markets and business conditions, with clients seeing double-digit percentage growth in revenue.

The algorithms driving each solution are developed by the team of PhD economists and backed by the team of software developers and data analysts. Each client is paired with a representative from the customer success team, ensuring a personalised touch.

Digonex solutions are tailored to strike a balance between revenue growth and other key objectives, including community accessibility, managing attendance at optimal levels, and fostering long-term customer loyalty.

Digonex's pricing solutions complement rather than replace its clients’ experience and market knowledge. It incorporates client-defined constraints and pricing rules directly into its solutions. Digonex clients can accept, reject or modify price recommendations through the user-friendly platform.

Clients include Herschend Family Entertainment, Royal Ontario Museum, Calgary Zoo, Toronto Zoo, Vancouver Aquarium, Zoos Victoria, BridgeClimb Sydney and Shedd Aquarium.

Attending the show will be CEO Pat Walsh alongside business development executives Scott Sauls, Chad Wallace, and Chelle Rupp. They are available in the Connect+ app.

DOF Robotics - booth #1369 & 1671

DOF Robotics, an award-winning producer of immersive simulation attractions, robotic systems, games, and CGI content, will unveil a brand-new attraction during IAAPA Expo 2025. The new product has been designed to push the boundaries of motion, storytelling, and technology.

Visitors to the booth can also discover AIQ and the Hurricane 360 VR simulator.

Additionally, The Smurfs: Gargamel Tower and Challenging Gravity will be on show at IAAPA Expo 2025 Orlando, offering new live experiences for the first time. Dog Fight is on the horizon, and the newly unveiled Phantom City will be explored in even greater depth during the event.

A press conference will be held on Tuesday 18 November at 11 am.

Downtown FabWorks

Downtown FabWorks, a leading provider of turnkey fabrication solutions for creative projects across the attractions industry, will also have a presence at the show.

Recent projects in Louisiana include Robin Roberts Broadcast Media News Studio & Interview Set at Southeastern Louisiana University in Hammond, and Bossier Parish Libraries History Center in Bossier City.

In New Orleands, it worked on various brand activations and live events for Super Bowl LIX, including a full-scale replica of New Orleans' famous Cabildo building facade for a private party in City Park.

The team also worked on Anne Rice: An All Saints' Day Celebration at the Orpheum Theater, Tate, Etienne, and Prevost (TEP) Interpretive Center, and Exhibits at Audubon Aquarium, Audubon Zoo, and Louisiana Children's Museum, all in New Orleans.

Elsewhere, the firm contributed to Culver's Field of Dreams Activation in Dyersville, Iowa, the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and multiple projects for Live Nation Entertainment at venues across the United States, including Riverside Amphitheatre Lanterns in Riverside, Missouri.

Earlier this year, Downtown FabWorks collaboration with AZZ Galvanizing - Baton Rouge on the Bucktown Bird’s Nest Learning Pavilion earned top recognition at the 2025 American Galvanizers Association (AGA) Excellence in Hot-Dip Galvanizing Awards. The firm also recently partnered with Scenario Global to deliver new exhibits for the reopened Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum.

Attendees can meet Daniel Krall, president and founder; Logan Onebane, sales manager; and Mattie Hanson, project manager

Dronisos - booth #2865

Dronisos, a leading drone light show specialist, will be presenting its different drone models (Boreas, Zephyr, and Helios). The team will also highlight its expertise in permanent drone installations for theme parks.

This year, the company will focus on XLabs during the show, its dedicated lab for developing robotic solutions for amusement parks. There will also be a daily Wine & Cheese gathering at 4 pm on the booth, welcoming delegates to meet and chat.

This summer, Dronisos continued its partnership with Dollywood for a fourth consecutive year with a drone show to mark the attraction's 40th anniversary.

Dollywood’s most spectacular drone show to date featured a brand-new story and, in a park first, included drones enhanced with pyrotechnics.

Camille Beaumont, general manager; Laurent Perchais, CEO; Leslie Paire Ficout, sales manager, and show managers Jonathan Corbett and Roy Ausburn will be present. Meetings can be scheduled here.

DTJ Design

Melding artistry in themed entertainment with multidisciplinary design, DTJ creates award-winning destinations worldwide. Its storytelling plays a vital role in placemaking, creating inspired and believable themed attractions worldwide.

The unique story of the place is reinforced at every design stage and level of detail, bringing clients' vision to life. When coupled with the firm's integrated design approach, it brings to life immersive environments rooted in guest experience.

With many award-winning projects in the DTJ Design portfolio, including Volcano Bay and Baha Bay Water Park (recipient of the World Travel Award's Caribbean's Leading Water Park award for three consecutive years), the team says it is excited to discuss possibilities at IAAPA.

The team will be on-site to share insights and discuss how they can help transform visions into a world-class destination. It also offers select private tours of local projects, providing an opportunity to see firsthand how DTJ’s design approach creates unforgettable guest experiences.

Attendees can meet John Torti, Dave Ignatew, Ting Jin, and Anastasia Grigoryeva.

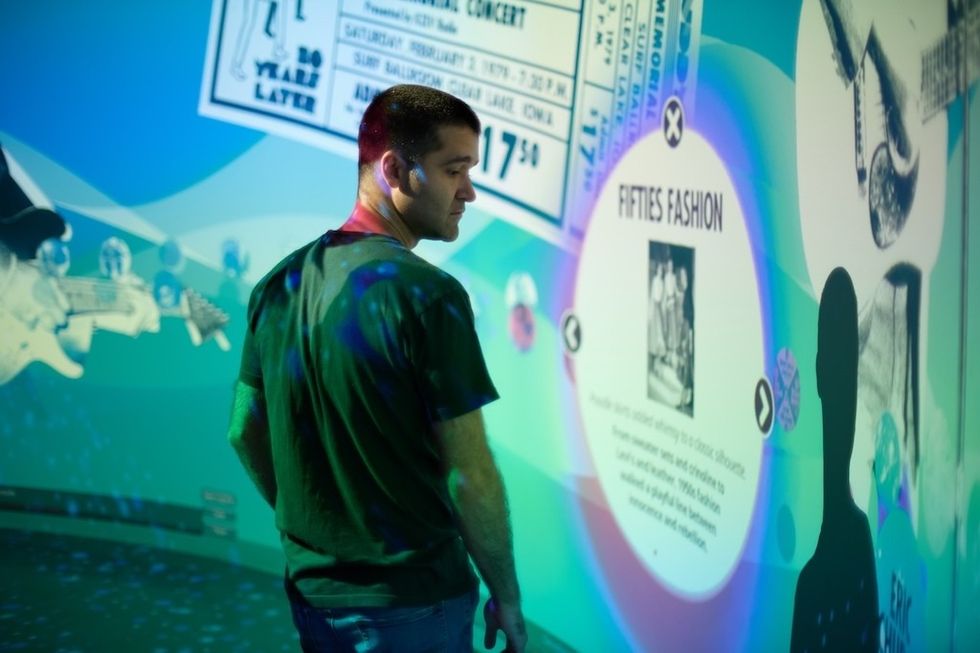

Electrosonic - booth #2069

Electrosonic, a leading international audiovisual and technology services company, is marking 40 years of membership with IAAPA. The company began exhibiting at the expo in 1986, while its membership dates back to 1983.

To mark this celebration, it will introduce a redesigned booth experience featuring the Electrosonic AV Garage, an AI-driven interactive tech experience inspired by the thrill of auto racing.

Created to fully immerse visitors in the dynamic world of motorsport, the AV Garage demonstrates how themed entertainment providers can utilise advanced audiovisual technology to captivate guests and create memorable experiences.

Guests will have the opportunity to explore four immersive zones, each showcasing unique applications of AI, interactivity, and experiential audiovisual technology.

Meetings can be booked here.

Electrosonic recently provided AV integration for the New Jersey Hall of Fame Entertainment and Learning Center (NJHOF ELC) at American Dream.

Embed - booth #1040

Embed, a leading worldwide supplier of point-of-sale and revenue management systems, will launch Embed AI.

Embed was awarded a coveted Google AI Cloud Takeoff spot, one of three selected from 10,000. Recipients received professional services, AI training, and Google Cloud credits to boost AI adoption.

This work resulted in the development of Sidequest AI, a new level of guest engagement designed to help customers craft hyper-personalised experiences through customised game recommendations.

With Embed AI’s deeper understanding of what operators need and want to achieve, Embed is bringing its entire hub home for a next-generation evolution.

Embed AI’s launch lives up to the Embed Ecosystem’s promise of 6-week cycles of innovation, featuring the new BOOKINGS, WAIVERS, SALES Roaming POS, and REPORTS—all designed to enable operators to run smarter and sell faster with the latest upgrades.

Recently, Embed also partnered with Windcave, a global payment platform, to expand into the unattended payments category, reflecting the company's ongoing dedication to supporting FECs of all sizes.

Environmental Street Furniture

Environmental Street Furniture (ESF), a supplier of exterior street furniture products, has announced that CEO Alan Lowry will be attending to network with partners, explore the latest trends shaping the sector, and strengthen the company’s global connections within the themed entertainment and leisure industries.

For ESF, a company recognised for combining design, sustainability, and storytelling in outdoor environments, it presents a vital opportunity to connect with creative leaders and explore how the latest developments in technology, design, and guest experience are shaping the future of public spaces.

Over the past year, ESF has broadened its international presence and continued to sharpen its focus on themed furniture through its dedicated brand, Theme Benches.

This expanding speciality helps attractions, museums, parks, and destinations transform outdoor seating and street furniture into parts of their storytelling.

Whether it’s a solar-powered smart bench, a bespoke themed seat, or sustainable furniture made from recycled materials, ESF continues to demonstrate how design can connect people, place, and purpose.

IAAPA 2025 will serve as a key platform for discussions on sustainability and experience design, areas where ESF remains a leader. The company’s strategy closely aligns with IAAPA’s environmental efforts, focusing on eco-friendly manufacturing, durable materials, and innovative reuse.

ETF Ride Systems - booth #4229

ETF Ride Systems, a leading ride designer and manufacturer, offers a broad range of ride concepts. From track-bound to trackless vehicles, whether on land, on water or above ground, every system can be tailored to meet the park's vision.

The vehicles seamlessly blend into the environment through theming and decorations that enhance storytelling and guest immersion.

At IAAPA Expo 2025, the team will showcase its latest rides and innovations, including the family of trackless vehicles that offer flexible routing, scalable capacities, and custom control systems to fit any narrative or spatial requirement.

One notable addition to the trackless family is the Dynamic Mover, a high-performance vehicle that features omnidirectional movement, advanced cabin rotation, an optical navigation system, and more.

The company will also provide updates on projects in development, such as The Enchanted Greenhouse at Six Flags Qiddiya City.

Jos Sloesen and Rob Reijnen are at the booth; meetings with them can be booked via email.

Falcon's Beyond - booth #2290

Falcon’s Beyond Global, a fully integrated development enterprise for IP-driven parks, resorts, media and merchandise, will exhibit at IAAPA Expo 2025

Attendees can schedule a time to meet with the Falcon’s Creative Group or Falcon’s Attractions teams by clicking here. The teams will also host a special happy hour on the tradeshow floor on Tuesday 18 November 18 from 4 - 6 pm.

Recently, Falcon’s Beyond Global announced a new collaboration with CD PROJEKT RED, a video game development studio, to create defined concepts for Cyberpunk 2077-themed venues. Falcon’s is currently appointed as CD PROJEKT RED’s global partner for all LBE activations.

In May, Falcon’s Beyond Global announced the acquisition of Oceaneering Entertainment Systems (OES), a division of Oceaneering International Inc.

In the transaction, Falcon's acquired OES’s global portfolio of patented technologies and exclusive engineering and manufacturing processes.

Fever - booth #4083

Fever is a premier global platform for discovering live entertainment, helping millions of people find the best local experiences.

The company encourages users to explore one-of-a-kind events and activities, from immersive exhibitions and interactive theatre to festivals and molecular cocktail pop-ups.

It has worked with some of the most prominent players across various industries, including Netflix, Universal, Disney, Exhibition Hub, Moment Factory, and more.

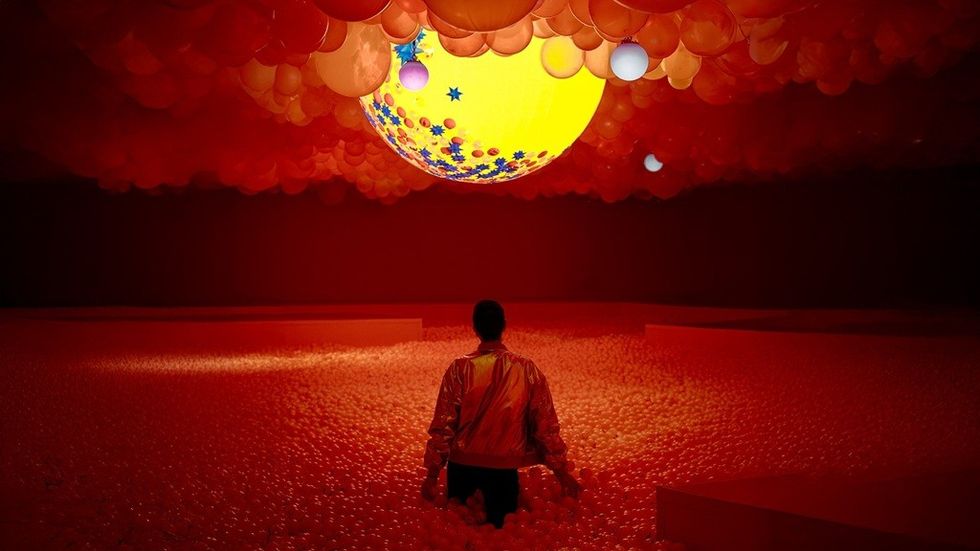

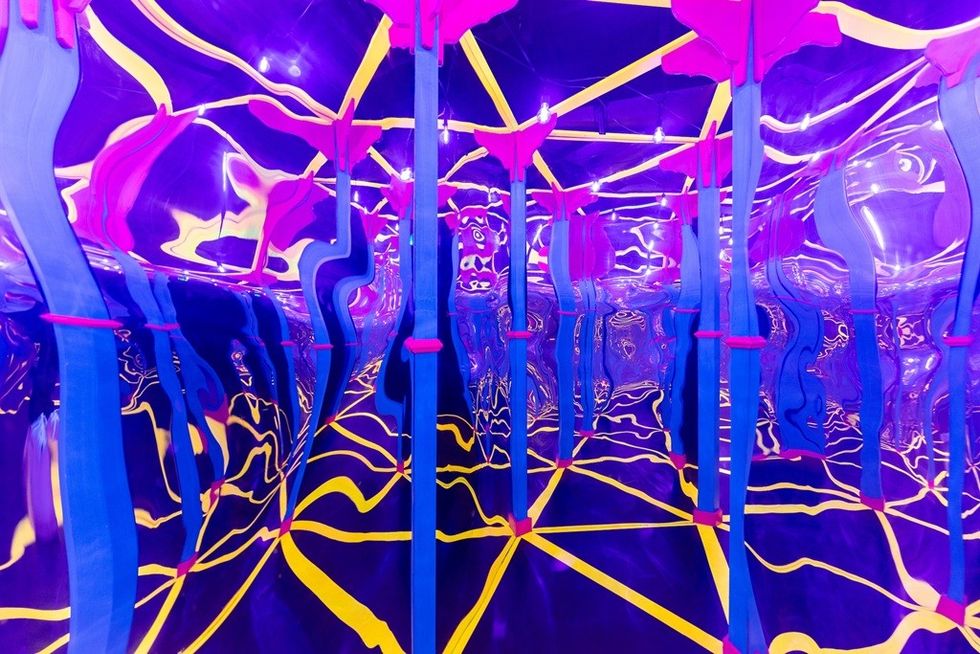

Super Neon experience Mall of America courtesy of Fever

Super Neon experience Mall of America courtesy of Fever

Attendees can meet Mariano Otero, SVP global; Santiago Muñoz, GM Mexico; Rajan Kalsi, GM Canada; Keaton Wyse, GM US; and Ethan Miller, business development, permanent attractions.

As noted above, Otero will lead the EDUSession, The Winning Formula: Combining Creativity & Data to Craft Scalable Immersive Experiences.

Framestore

Attendees can meet the immersive team from award-winning studio, Framestore, at IAAPA Expo 2025.

Joining this year's expo are a team of cross-disciplinary creatives, including Mike McGee, chief creative officer; Karl Woolley, global head of immersive; Heather Kinal, senior VP - immersive; Maximilian McNair MacEwan, head of strategic partnerships - immersive; David Michaels, business development executive; and creative directors Gavin Fox, Jason Fox, and Gareth Smy.

Throughout the week, the team will be connecting with industry partners and clients to explore new opportunities and collaborations. Click here to book.

Framestore will host a special fireside chat on Monday featuring legendary creative Joe Rohde in conversation with co-founder McGee. Together, they’ll reflect on their remarkable careers and share insights from decades of experience operating at the highest level in the creative fields of Hollywood and themed entertainment.

FORREC - booth #2669

FORREC, a leading entertainment design specialist, will share some of its successes from this year, including the grand opening of Legoland Shanghai Resort.

In partnership with Merlin Entertainments, FORREC led experience design, master planning, and detailed design for the theme park and hotel.

The firm also delivered master planning and concept design for the Aegean Bingo RDE in Jinshan and collaborated with Chimelong in Guangzhou on its Super Park's creative vision.

FORREC partnered with Intamin to create Gyeongju World’s Time Rider Coaster Wheel as a signature attraction, enhancing guest experience. In Brazil, FORREC teamed with Beto Carrero World to launch its first off-park retail store at Florianópolis Airport.

Back in Canada, FORREC partnered with Brogent Technologies, working closely with local Indigenous groups to create the immersive Niagara Takes Flight flying theatre and pre-show experience, which tells the story of Niagara Falls in an authentic new way.

A large team will be in attendance, and meetings can be booked via email.

Forward Thinking Designs - booth #573

Forward Thinking Designs, a provider of advanced AV solutions for the themed entertainment industry, is celebrating a decade of delivering innovative, high-quality AV solutions to clients.

At this year’s event, visitors to the booth can learn about the integrated approach that helps clients achieve seamless project delivery, greater efficiency, and measurable results.

The team will demo the full suite of services, ranging from design and programming services to custom-developed solutions.

Following the recent partnership with Audio by the Bay, ForwardThinking Designs will share a booth with the Audio by the Bay team, who will host immersive audio sessions each day.

At 11 pm, Immersive Audio: Just a Gimmick? When and How to Expand Your Soundscape, will delve into the concept of Immersive in the realm of aural environments and storytelling, exploring some of the most prevalent tools and techniques.

At 1 pm, Expanded Sound Design: Using Immersive Audio to Enhance the Story will take a journey from spectaculars such as Beyond All Boundaries from the National WWII Museum to dining experiences that are out of this world.

Then, at 3 pm, Custom Music: Is It Really Too Expensive? will look at the creative process, showcasing projects ranging from cost-effective endeavours to collaborations with the world’s finest musicians in premier studios.

The Forward Thinking Designs team will include Evan Hall, chief of big ideas; Rob Pourciau, futurist; Andrew Davis, mastermind of hype; and James Bengel, hype facilitator.

From Audio by the Bay, Dan Scott, mastermind of music and post, and president Joe Pileggi will attend.

Frontgrid - booth #1765

Frontgrid, an expert in adventure leisure and virtual reality attractions, and the creator of ParadropVR, will take stand visitors through our new credentials and portfolio, including a short 360-degree film demo in a headset.

Frontgrid blends engineering, immersive content, and design to create iconic experiences.

In 2025, it launched two world firsts: Niagara Virtual, a gamified flying experience over Niagara Falls in the USA (a Brass Ring finalist), and Containerised Pod, enabling VR flying experiences at outdoor locations, with its first location opening in Poland.

The company also provides custom hardware and software, immersive content, and venue consultancy, now operating in 16 countries worldwide.

Frontgrid coined the entertainment category of location-based flying, which involves creating immersive experiences that fly over real-world-inspired environments. This offers a futuristic solution for tourist destinations, providing visitors with a new way to explore and learn about places.

Matt Wells, chief executive; Tammy Owens, business development director and producer; and Jack Wells, account manager, will attend. Meetings can be scheduled by email.

Gateway Ticketing Systems - booth #4847

Gateway Ticketing Systems, a leading provider of admission control systems, will showcase its latest innovations. Visitors can explore how Gateway’s Galaxy platform continues to evolve, delivering seamless data-driven guest journeys from purchase to entry and beyond.

See also: Optimising for the digital-first guest journey

This year, Gateway proudly introduces its reimagined Galaxy web store, built to transform the way guests plan and purchase their visits.

Designed with a fresh, intuitive look and faster performance, the new web store gives attractions more control over how they present offerings and guide guests to the right experience.

It brings a smoother, more engaging online journey that feels natural and familiar to modern buyers, helping venues inspire confidence, boost conversion, and grow online revenue. From first click to final confirmation, the buying experience is clear, simple, and built around what today’s guests expect.

Gateway will also feature integrated digital waivers and SMS ticket delivery, giving guests a seamless start to their day. With waivers completed before arrival and tickets sent directly by text, visitors can head straight to the fun while attractions keep lines moving and reduce congestion at key entry points.

These tools are part of a growing suite of pre-arrival capabilities designed to put guests fully in control of their visit and support smoother operations for the venue.

Together with improvements to front-gate and onsite sales through the enhanced Galaxy retail kiosk, Galaxy continues to deliver a complete solution for ticketing, admissions, and guest engagement.

To schedule a meeting, delegates can use the Connect+ app.

GoPhoto - booth #1383

GoPhoto, an Amsterdam-based technology company redefining the art and business of photography within the visitor attractions industry, is showcasing the AI Creation Station.

This merges generative AI with photo retail to create endlessly personalised souvenirs. Visitors simply take a selfie and, within moments, can see themselves reimagined as anything from an astronaut to a zookeeper, or even as the subject of a Van Gogh painting.

The system uses sophisticated, theme-based AI models customised to each location or IP, ensuring on-brand, context-aware creations. All processing occurs within GoPhoto’s proprietary ecosystem, eliminating the need for third-party integrations or external data sharing.

By integrating advanced automation and generative AI, the company is empowering attraction operators to streamline their workflows and create truly unforgettable guest experiences.

See also: Capturing lasting memories at Ripley’s attractions with GoPhoto

In the past month, GoPhoto launched at a record 20 new locations worldwide, helping operators build the most efficient and engaging photo retail ecosystems possible.

It is trusted by industry-leading brands, including Ripley Entertainment, as well as touring exhibitions such as Jurassic: The Experience and F1: The Exhibition.

Daniel Duivestein, founder and CEO, and Kieth Hilgersom, global sales manager, will be present. Meetings can be arranged by email.

IAAPI - booth #4035

The Indian Association of Amusement Parks and Industries (IAAPI) will be present at IAAPA Expo 2025. Attendees can learn how to book a booth at the IAAPI Amusement Expo 2026, where they can explore the India Market.

The event will take place from 10 to 12 March 2026 at Hall 4, Bombay Exhibition Centre, Mumbai, India. It is a premier event for the amusement and entertainment industry, providing a platform for companies to showcase their products and services to a targeted audience of industry professionals and buyers.

It is a great opportunity to network with industry leaders, generate leads, and promote brands to a broader audience.

Immotion - booth #1362

Immotion, a global leader in immersive edutainment, will present its VR Immersive Attractions.

The team will have two sample installations on the show floor: a climate-controlled, enclosed container and a standalone installation with Lumiwall and pods. In addition, the company will debut the first-ever sneak-peek trailer of its upcoming 2026 film, Polar Odyssey.

Visitors can book time with Rod Findley, president; Stacy Ignacio, global head of partnerships; and Mark Whittaker, partnerships director for Europe, by email.

Recently, Immotion's VR film Dolphins of the Reef was awarded Best of VR by the Los Angeles Film Awards (LAFA).

It continues to raise awareness of conservation and education through its immersive virtual reality experiences, crafting memorable adventures that connect visitors with the natural world.

Inowize - booth #4274

Inowize, a creative company delivering interactive experiences, will demonstrate QBIX, a 6-player immersive gaming room suitable for groups, with high throughput and fully unattended capabilities.

New this year is the Redemption integration, which connects immersive group gameplay to a prize-based experience and will premiere at the show.

The team will also show Last Defense, its ninth title, featuring multi-screen movement, team collaboration, and dynamic levels.

Inowize is now present on every continent with new installations across Europe, the Middle East, North America, and APAC, including the US, Canada, Spain, France, and Japan.

The team will also participate in Redemption Meets Immersion: Reinventing Group Gameplay on 20 November at 11:30.

At the booth will be Stefan Murariu, head of sales; founders Claudia Mihalache and Ovidiu Mihalache; and Greg Smith, USA director of sales. Meetings are available here.

Intamin - booth #3825

Intamin, a creator of record-breaking amusement rides, has announced three new flume ride elements: the Diagonal Drop, Swing Splash, and Bungee Lift.

These three new elements join Intamin’s lineup of special features, which already includes the popular Booster and V-Switch, offering a selection to elevate any flume ride into something extraordinary.

Intamin’s latest flume ride special elements are available for all projects. Inspired by the growing demand to excite and immerse guests with captivating stories and fresh experiences, the Intamin team drew inspiration from its latest roller coaster innovations to develop these three new elements.

Furthermore, Intamin will unveil another new immersive ride system during the show.

Earlier this year, Intamin celebrated the opening of Time Rider, a new centrepiece attraction at Gyeongju World in South Korea.

Lagotronics - booth #2075

This year's achievements in interactive attractions include

Ghostly Manor, the richly awarded Gameplay Theater at Paultons Park, which has been nominated for an IAAPA Brass Ring Award for Best New Product.

Visitors to the booth can get hands-on with the company’s devices and experience the quality that defines Lagotronics Projects’ attractions around the world.

CEO

Mark Beumers, CTO

Jacco Groen in ’t Wout, and account manager

Michael Thiesen will be available throughout the show to discuss ongoing projects, upcoming openings, and the future of interactive technology. To arrange a meeting, get in touch by

email.

Leisure Development Partners - booth #2064

Leisure Development Partners (LDP), a leading economic and strategy consulting firm, will release the new edition of The Experience Economist, focusing on The Americas, in addition to the speaking engagements detailed above.

At 12 noon on Thursday 20 November, the team will present a sneak peek at this insightful and valuable content.

At the booth will be Frea Nunn, marketing and operations manager; Michael Collins, senior partner; Yael Coifman, senior partner; James Kennard, partner; Natalia Bakhlina, partner; Kathleen LaClair, partner of LDP Americas; Sam Davey, senior associate; and Megan Hiatt, senior associate.

Visitors can book meetings by email.

Lumsden

James Dwyer is creative director and CEO of Lumsden, a design firm specialising in retail and F&B for visitor attraction.

Lumsden’s clients include Netflix Experiences, Warner Bros. Studio Tour London and Tokyo, the Flagship Harry Potter stores in Chicago and Harajuku, MoMA, the British Museum, M+ Hong Kong, the National Gallery and Royal National Theatre, London.

The studio's approach weaves storytelling, immersive design and themed environments to create shopping and dining experiences that engage audiences and deliver lasting commercial success worldwide.

Dwyer will be at IAAPA all week and can be contacted by email.

Martin & Vleminckx - booth #4827

Martin & Vleminckx (MV Rides), a leader in designing, manufacturing, fabricating, and installing thrilling attractions, will unveil a lineup of rides designed to redefine the guest experience.

This includes G-Storm, a high-intensity ride that launches guests back and forth on a massive gondola, navigating a dynamic track suspended between two towering structures.

Polercoaster is a revolutionary vertical roller coaster that provides an exhilarating experience within a remarkably compact footprint, while SkySpire is an architectural tower offering 360-degree panoramic views from climate-controlled gondolas.

Unicoaster 2.0 is an interactive, next-generation coaster that features patented rotating seats, allowing riders to have complete control over their experience along the track.

In addition, the company is the exclusive North American distributor for The Seasonal Group and will also showcase Immersive Experiences Rides and premium Animatronic products that bring storytelling to life at booth #4844.

To make the most of the event, visitors can schedule a meeting in advance by email.

Martin Aquatic - booth #1840

Martin Aquatic, a world-class aquatic firm, will present its newest projects, including Carnival Cruise Line’s Celebration Key, which features the two largest freshwater lagoons in the Caribbean powered by its patented Blue Mar Basins technology.

Visitors can also discover the firm's new innovation, the powerful Blue Mar Nova submersible light. Plus, the team will be making some announcements about the expanded offerings of its experiential design division, Ectovox, and its exciting new projects.

Team members at the booth include Josh Martin, president and creative director; Matt Kent, VP of business development; Alessandro Orio, VP Blue Mar Basins; Diego Cordova, technical director; JT Toavs, studio director; Matt Johnston, studio director; and Chris Grap, creative director.

Meetings can be booked by reaching out to Matt Kent.

MediaMation - booth #667

MediaMation, a leading design, interactive, and motion simulation technology company and a pioneer in 4D Motion EFX Theatres worldwide, will showcase the MX4D “Bantam” Flying Theater project, a hybrid of its successful flying theatres and standard MX4D Motion EFX seats.

The Bantam Flying Theater provides virtually the same exhilarating, “soaring” experience for smaller venues or for use with VR at an economical price point.

MediaMation will also feature ShowFlow Lite, an offshoot of the award-winning ShowFlow software. ShowFlow Lite has the punch of a complete control system in an economical, compact microcomputer format.

Attendees can also see the Vidshow/ShowFlow video server/show control system. The actual size is decreased by 50%, the power is increased, and it supports new features, third-party modules, and provides up to 4K – 3D video capabilities built in.

Coupled with the ShowFlow Lite touchscreen devices, this upgrade provides even better and more economical control/video/audio in one system.

The company has provided the entertainment industry with complex solutions for attractions, interactive exhibits, theatres, cinemas, fountains, and VR for the past 34 years. With installs in 34+ countries, its award-winning patented technology is sought after globally.

Clients include F1 – Las Vegas, Kennedy Space Center, Legoland, Disneyland, Epcot Center, Universal Studios, Mattel Adventure Park, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, to name a few.

Visitors can book meetings with Chase Jamele, sales and marketing coordinator.

Mobaro - booth #4409

Mobaro, a provider of online maintenance and safety solutions, will unveil new strategic partnerships and product features, including EllisDocs powered by Mobaro, Inventory Management, and RideOps 2.0.

Delegates can meet David Bromilow, global director, parks and attractions; Marah Rodriguez, regional VP of sales, North America; Megan Gannon, solution sales manager, North America; Logan Bowlby, senior customer success manager; Patrick Gorham, senior customer success manager; James Lane, customer success manager; Christian Rasmussen, CTO; Sigurd Vilstrup, head of professional services; Henrik F. Have, co-CEO and co-founder, and Christoffer W. Borup, co-CEO and co-founder.

Book a meeting here.

Earlier this year, Mobaro announced a new partnership with DMT, a TÜV NORD GROUP company, to enable amusement parks to manage ride maintenance more quickly, safely, and efficiently.

NeoPangea

NeoPangea, an experiential media design and production studio, will have a team walking the show floor.

Recent projects include introducing a blend of playful interactivity and cinematic storytellingntroducing a blend of playful interactivity and cinematic storytelling to the Milken Center for Advancing the American Dream (MCAAD), a new cultural centre in the heart of Washington, D.C.

Meanwhile, in China, the firm is pushing boundaries and tapping into bold, creative thinking with a new museum, visitor centre, and thematic experience focused on extending and improving life: a Longevity Museum in Chongqing, China.

Founder and baron of pixels, Brett Bagenstose, has recorded numerous sessions for NeoPangea's Proof Lab series.

This is the company's own streaming series, showcasing its thinking and R&D. Each episode delves into a real-world creative or technical challenge and walks through how it was solved.

From digital installations to rapid prototypes, the episodes pull back the curtain on the team's process and invite collaborators to chime in, too.

Delegates can meet with Bagenstose, as well as Jen Wallace, VP of client strategy and marketing, and Emily Rhinehart, director of client strategy, by sending an email.

nWave Studios - booth #2060

nWave Studios, a multinational producer and distributor of immersive 3D/4D content, released two new films this year, which attendees can learn more about during the show.

In May, the studio released Drone Dash, an ultra-immersive 3D/4D ride film produced in collaboration with Red Star. In September, Meg and the Quest for the Holy Spork, a 3D/4D ten-minute family adventure, premiered at IAAPA Expo Europe. This was followed by the debut of both films in parks this year.

At the show will be Goedele Gillis, senior vice president for sales and distribution; and Matthieu Gondinet, COO. Visitors can reserve a time slot via email.

ProIO and Practical Imagination

Joining forces at the show will be two Orlando-based companies with broad reach: ProIO, a technology consulting company specialising in immersive experiences and attractions for the themed entertainment sector, and Practical Imagination, which offers creative treatment, design, and fabrication.

Working in collaboration, the two companies can provide turnkey solutions for themed entertainment projects, from ideation to delivery and beyond.

ProIO will be represented by CEO Brice Helman, VP Bryan Maier, and associate project manager Mei Lu. Practical Imagination's president, Andrew Curran, will be at the show as well. Meetings can be booked by sending an email.

Recently, Helman and Maier spoke to blooloop about how the teams’ wealth of experience across the visitor attractions and location-based entertainment industries is helping to manage, create, and deliver innovative solutions for rides, themed attractions, museums, entertainment venues, and more.

ProSlide - booth #2254

ProSlide Technology Inc., an industry leader in water ride manufacturing and design, returns to IAAPA Expo 2025 with its largest team presence of the year, ready to showcase the next generation of ride innovation.

The week begins with industry events supported by ProSlide, including the Water Park Operators’ Welcome Event at the Hyatt Regency, where industry leaders share ideas and inspiration for water park entertainment worldwide.

As detailed above, ProSlide moderates the Unlocking the Potential of Water Park Operations After Dark EDUSession.

On Tuesday 18 November, the company will make a major attraction announcement on the booth at 3.10 pm.

During the show, it will also debut world-class water park projects and new installations across global markets, including Xocomil (Guatemala), Aqualandia (Chile), Vung Tau (Vietnam), Roaring Springs (USA), Seabreeze (USA), Reefsedge (Australia), Lost Paradise of Dilmun (Bahrain), and more for 2026.

Attendees can meet Rick Hunter, founder & CEO; Ray Smegal, president; Jeff Janovich, SVP of global strategic partnerships; Phil Hayles, SVP of business development and strategic accounts; Steve Avery, SVP of business development for APAC; Nik Paas, SVP of business development and strategic accounts; and Aaron Wilson, SVP of business development for EMEA & LATAM.

Meetings can be booked by email.

RCI Adventure Products - booth #5424

RCI Adventure Products, a leading adventure attractions company, has designed, manufactured and installed almost two dozen attractions since IAAPA 2024.

In the winter, the team completed the installation of a Sky Trail course, featuring a 180-degree Sky Rail and an integrated Adventure Trail, its net-play course, at the brand-new Great Wolf Lodge in Connecticut.

Nearby in West Palm Beach, it completed the installation of a 2-level outdoor Sky Trail course, featuring a 60-plus-foot Sky Rail, for Shark Wake Park in May.

The Fun Station in Cedar Rapids, IA, celebrated its grand opening last month, and RCI installed a 3-level Sky Trail course with 2 150-foot-plus Sky Rail ziprail rides and 9 Clip ‘n Climb walls.

Longtime customer Riverbanks Zoo & Garden in Columbia, SC, opted for a Sky Tykes, the firm's low-ropes course designed for kids, in July.

The team also installed a brand-new Sky Tour zip experience for Allegan Event this summer. The course includes six curved Sky Rail ziprails totalling over 700 feet.

Ronda Hulst and CK Foo will represent the company at the show.

Research Casting International - booth #675

Research Casting International (RCI), an expert in the preservation, restoration, and fabrication of museum specimens, will highlight recent work overseas, including custom theming work.

One project closer to home is the installation of an 18-metre skeleton of a blue whale for Steele Ocean Sciences Building on the Dalhousie University campus in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

RCI completed the installation over five days in late February, transporting the bones from the company’s facility in Trenton, Ontario, where they had been in storage since 2021.

RCI's skeleton crew was also recently brought in to refurbish, remount and repose several of the historic skeletons at Yale Peabody Museum, as the building underwent a transformative renovation.

Chris Hogarth, marketing manager; Patrick Fair, sales manager; and Owen Payette, marketing and sales coordinator, are attending.

RES Rides - booth #4404

RES RIDES, the Swiss ride engineering company, will mark its 10th Anniversary at IAAPA Expo 2025.

The firm's Pumpen Super Swing at Gröna Lund (Parks and Resorts Scandinavia) earned the European Star Award for Europe’s Best New Big Attractions 2025 and is a 2025 Brass Rings finalist for Best New Family Ride Attraction.

Visitors to the booth can discover the firm's lineup of crowd-pleasers, including the top-selling Roller Ball, as well as the Interactive Observation Tower and the Super Swing.

See also: Innovation in attractions: from Ride Engineers Switzerland to RES RIDES

Meetings can be arranged here.

RocketRez - booth #4459

RocketRez, the end-to-end cloud ticketing platform for tours and attractions, connects every guest transaction, from ticketing to food, T-shirts, and memberships, on a single, powerful platform.

At the show, the team will showcase a range of tools designed to modernise operations and enhance every moment of the guest experience.

These include a flexible ticketing engine capable of handling complex scenarios, such as timed entry, groups, upsells, and multi-channel sales, that sync in real-time.

They will also present a unified Point of Sale (POS) system that streamlines retail, food and beverage, and rentals, reducing queue times and allowing guests to enjoy attractions more quickly.

Additionally, a dynamic insights reporting suite will convert guest and transaction data into visual dashboards, informing decisions related to pricing, staffing, and revenue.

Lastly, the Relay platform offers automated, personalised communication that delivers real-time messages before, during, and after a visit to ensure a seamless guest experience.

See also: Relay by RocketRez: seamless & personal guest communication

Plus, in the RocketRez Confessional Booth, operators spill their summer stories, the wins, the wrecks, and everything in between.

There will be a large team at the booth, and meetings can be booked here.

ROLLER - booth #3047

ROLLER, the ticketing, CRM, and POS specialist, will demonstrate how its all-in-one platform helps venues simplify operations, grow revenue, and delight guests.

Visitors to the booth can explore the full suite of venue management tools, including online booking, party management, membership management, digital waivers, reporting, and more.

Plus, for the first time, it will show the newest innovation: ROLLER iQ iQ. IAAPA attendees will be among the first in the world to see this purpose-built intelligent AI assistant for attractions.

Luke Finn, CEO and founder; Luke Sims, CEO of BookNow; Rich Steers, chief product and technology officer; Ash Fagura, chief revenue officer; Greg Ruh, VP of sales; Alyse Sklover, senior events and partnerships manager; and more, will be at the show.

Schedule time with the team by email.

Rovio

Rovio Entertainment Corporation, a Finnish mobile-first gaming company and creator of the Angry Birds brand, has a platinum sponsorship with IAAPA, with an epic Angry Birds 3D photo opportunity at the South Concourse hall.

At the event, the team will be representing Angry Birds, a brand that can elevate any attraction and location. Latest partnerships include ones with Raw Thrills and Sea Life.

It has joined forces with Raw Thrills and Play Mechanix to present a new arcade machine based on the Angry Birds franchise, available for family entertainment centres worldwide.

Additionally, it has partnered with Merlin Entertainments to create an educational experience featuring Angry Birds, enabling families to help protect oceans at Sea Life venues.

The Rovio team is attending and available for meetings, including Katri Chacona, head of brand licensing; Ilkka Heino, senior creative manager; and Selina Koskela, marketing manager

RWS Global

RWS Global, a leading producer of live experiences, has achieved multiple successes throughout 2025, creating over one million live moments daily for guests on land and at sea.

Recent theme park projects have involved creating over 30 Halloween activations worldwide at attractions such as Alton Towers, Chessington, Legoland Windsor, Hersheypark, and Elitch Gardens. These projects establish RWS Global as one of the world's largest Halloween activation producers.