By Carolyn Collins Petersen, Vice-president, Loch Ness Productions

Naturally, the writer has to provide words that synchronize with accompanying images and multimedia. But, the whole message – words, images, media – has to fit into what is usually a very tightly designed space. Thus, captions often are not more than 50-100 words long (sometimes less). The words have to be honed carefully and the writer needs to do so with a great deal of insight into the visitor’s mind and interests.

This is work that requires the services of a specialist who can write and research science, do it under deadline (expecially when there are opening deadline pressures), and do it as part of a team effort. Exhibits don’t just make themselves – there are artists, creative directors, fabricators, editors, producers and curators all involved in the process, each with special insight into the process.

I’ve been writing exhibits for a few years now and I’ve learned some valuable lessons about this tricky business. Each project is different, but the fundamentals are the same: to create engaging exhibits that excite people about the subject at hand.

Because science exhibits focus on presenting complex information in approachable language, the writer has to be especially adept at finding just the right words to help exhibit designers grasp the concepts they are working to illustrate. Savvy writers need to “speak design” – so that when the inevitable conflicts about “white space” and layout come up, they can make it clear (for example) why cutting out an entire paragraph for the sake of a layout grid may not be wise.

As an exhibit writer, I’ve often found myself in the role of the science interpreter, advocating for the visitor to curators or scientists or exhibit designers who don’t always have that same insight I do about how to write science for the public. It’s a delicate juggling act that requires diplomacy and tact under pressure.

Two Experiences as Illustration

A few years ago, I got the call to work on the exhibits for Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, California. The facility, beloved of all Angelenos, was closed for nearly five years for renovation and expansion. Part of that refurbishment was a complete re-creation of and additions to its astronomy exhibits. The design team was led by C&G Partners of New York City, who worked with vendors across the U.S. to create and design the exhibits. The entire project was created “out of house” (rather than by Griffith employees), and the designers and exhibit staff explicitly specified an outside writer with an independent viewpoint to do the exhibits.

As most museums and science center staffers (should) do, Griffith crafted a visitor’s experience manual to guide the language level and general approach for the exhibits. It was up to me to create a written “voice” that would speak to and engage the visitor.

Just as an actor prepares for a role, I devised what we called the “Observatory Voice” and that became the character I “played” as I wrote the material. I worked extremely closely with the design team, and in fact, I was “embedded” at C&G Partners for nine months out of the year and a half I was on the project. This kept me in constant, daily touch with the artists as they fine-tuned the exhibit layout and design. Our joint creation was and is an extremely approachable and timeless exhibition that excites people about astronomy.

In 2008, I reprised the role of science exhibit writer farther upstate, for the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. This time I wasn’t responsible for an entire building full of exhibits, but rather a finely honed series of panels about global warming and climate change. In addition, I worked with two filmmakers to shape onscreen captioning for a series of striking videos about climate change.

The challenges were huge: I was brought in less than five months before the exhibits were due to open and there was a large amount of information to assimilate and shape into pithy, engaging language. Fortunately, I had a wonderful team to rely on: a research and support staff engaged by Cinnabar California as well as curators and resource scientists from the Academy itself. With their help, and the support of Cinnabar’s Jonathan Katz, I was able to write exhibit text that engages the visitors emotionally and intellectually about some very timely and contentious issues.

For both projects, it was quite a challenge to shape language into the tightly scripted regime of exhibit panels. Now that I’ve done it for these (and other) exhibits, I find myself paying close attention to exhibit language when I go to new museums, science centers, zoos, and aquarium facilities. Each one is a learning experience that I can carry forward to future exhibit projects where a writer is needed to help convey the beauty and excitement of science.

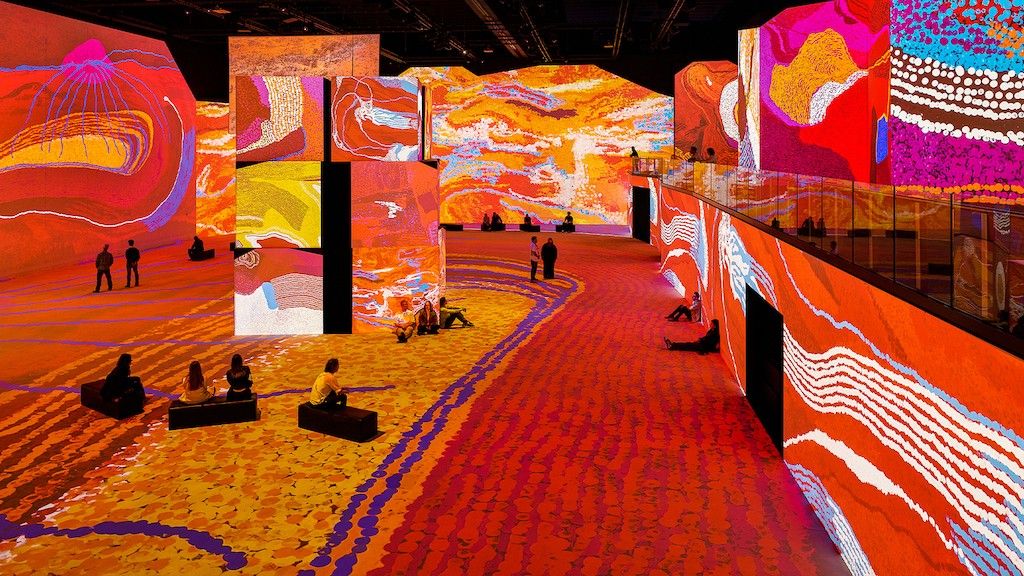

Images: Exhibits at Griffith Observatory, courtesy of author. From top,

1. The Visible-Light Universe. The visible-light universe is the most accessible and is our entry into astronomy. It is what humans observed first using our visible-light-sensitive eyes.

2. Beyond the Visible Exhibit. Each circular image in this beautiful exhibit is like a window into another part of the electromagnetic spectrum. We wanted visitors to understand not only what things look like in other wavelengths, but how astronomers can use these wavelengths to probe "unseen" regions our eyes could never detect without help.

See Carolyn’s archive here

Fulldome: Global Immersion’s Martin Howe talks about the Morrison Planetarium at the new California Academy of Sciences