As always, the event also served as the stage for unveiling the 2025 blooloop Innovation Awards, presented in partnership with Area15, with winners announced live after their respective session categories.

Whether you’re a veteran operator, designer, technologist, or experience creator, the Festival’s 2026 edition offered a panoramic view of how innovation continues to evolve, from reimagining guest experiences and immersive worlds to expanding accessibility and creative technologies that spark future growth.

Day one at the blooloop Festival of Innovation 2026

Storytelling and culture, sponsored by QSAS

Day one began with panellists Sara Bou-Holaigah, strategy & ventures director at QSAS; Abeer Albahrani, museum consultant; Mohammed AlModhayan, CEO of VisitSaudi; and Yousef AlSharef, creative technologist at QSAS, discussing cultural storytelling.

“Cultural immersiveness is when you can turn someone that arrives at a destination with curiosity… and transform them into someone that leaves the destination with a new perspective.”

That powerful definition from AlModhayan set the tone for an exploration of how cultural storytelling is evolving across museums, destinations, and immersive experiences. The discussion highlighted a shift from passive observation to engaging, participatory worlds where culture is lived rather than presented.

As Albahrani noted, today’s visitors “no longer want to just read labels and see artefacts and objects behind the glass.”

Audiences seek deeper engagement, wanting to experience culture emotionally and physically, not just consume it. The challenge for designers and operators is to go beyond display and interpretation, crafting experiences that address shared human truths.

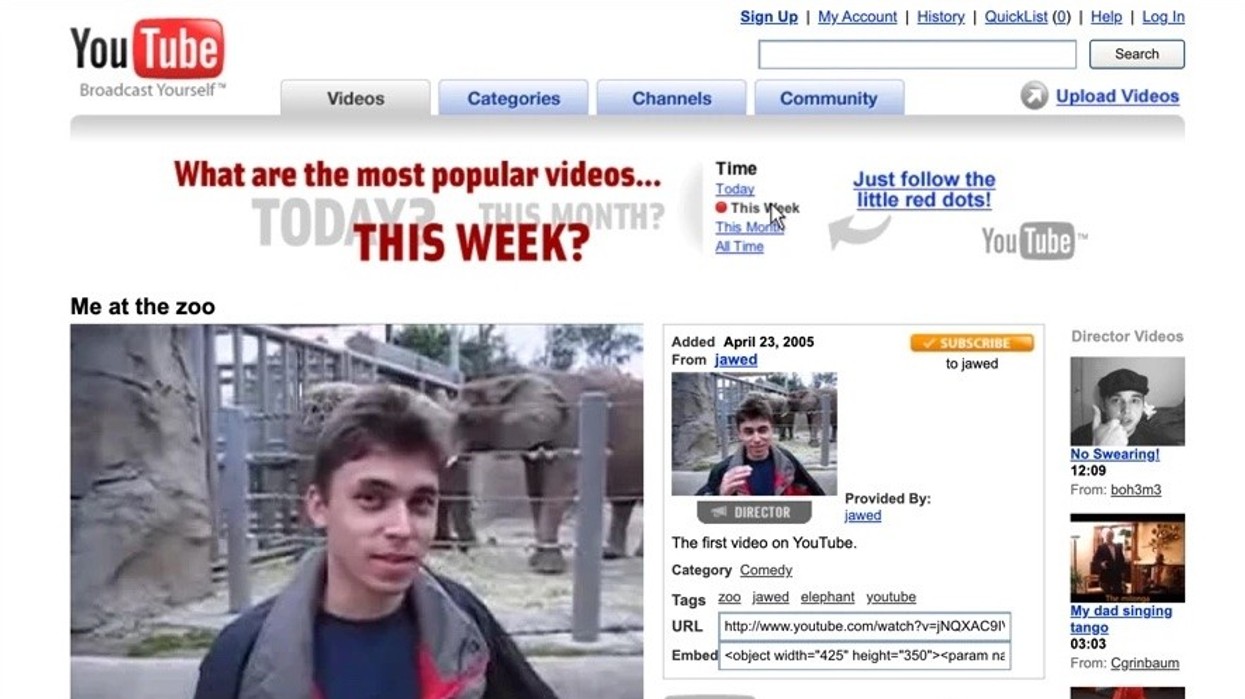

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Pavilion at Expo 2025

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Pavilion at Expo 2025

When creating programmes for both local and global audiences, Albahrani emphasised the importance of focusing on “the emotional, the core human centre that everybody has a share and connection.”

Cultural specificity is vital, but it's the human story that creates cross-border connection.

Technology, the panel agreed, plays an important but carefully calibrated role. As AlSharef articulated, immersive storytelling means designing systems where culture “isn’t explained to you – it’s actually felt.”

In this model, technology quietly influences emotion and memory without becoming the focus. The headline is the human impact, not the hardware.

AlModhayan emphasised that subcultures shape a destination’s identity. Authenticity stems from embracing layered narratives and empowering “human narrators” who can translate culture with sincerity and nuance.

Success isn't about production or wow-factor but about transformation: creating a lasting memory, shifting perspectives, and subtly changing visitors. As technology advances, the panel emphasised that cultural immersion's future hinges on storytelling and emotional impact, not spectacle.

Winners of the Storytelling - culture award, sponsored by QSAS

1st place: National WWI Museum and Memorial - Encounters Exhibition

2nd place: Bob Marley: Hope Road

3rd place: BRC Imagination Arts' SCADstory Atlanta

Innovation in technology, sponsored by Holovis

Next, guests at the Festival of Innovation heard from Keely McClarin, vice president of global PMO at Holovis, and Annie Cantele, project manager at THG Creative, for a grounded conversation about what meaningful innovation really looks like in 2026.

For Cantele, the starting point is never the tech itself. “A lot of times we will talk about our experience having heart,” she said. “That’s the easiest way to reach a wide audience… give them an experience that they can relate to, and they can empathise with.”

At THG, a guest-centric philosophy guides all decisions, prioritising emotional resonance over technical spectacle. That focus feels increasingly important as AI and hyper-real digital content reshape expectations.

As audiences consume ever more sophisticated digital content, the benchmark for physical experiences rises in parallel. “The bar is set so much higher now for those of us who are designing experience… This is what people want. Now, we have to get there, right? And how do we create that in a way that is real?”

Delivering on that promise requires difficult conversations. New technologies cost more due to unknowns about integration, longevity, and operational demands. Managing client expectations is crucial. If a project involves cutting-edge innovation, teams must be transparent or suggest alternatives.

Whisper Box from Losonnante.

Whisper Box from Losonnante.

“Those are not always the most comfortable conversations,” Cantele said, but they're necessary to align ambition with reality.

McClarin emphasised the importance of balance, noting that 'the physical aspect is still so important' and that blending technology with tangible design allows storytelling.

For Holovis, magic occurs where spatial design and digital systems enhance each other rather than compete. Although budget constraints are challenging, McClarin sees them as opportunities for smarter innovation rather than obstacles.

Both speakers stressed that early collaboration among designers, engineers, and operators. Considering operational realities, maintenance, and lifecycle costs from the start ensures that immersive experiences remain robust in the long term.

The session highlighted that in a fast-changing tech world, real innovation isn’t about chasing the latest tool but using it purposefully. When technology serves storytelling and heart guides, the experience feels authentic, not just impressive.

Winners of the Creative Technology award, sponsored by Holovis

Winners of the Experiential Technology award

1st place: Beyond Endings Metahumans from MOD

2nd place: American Wave Machines, Inc.'s PerfectSwell Gen 6

3rd place: ScreamScore

From access to impact: innovation in exhibits, sponsored by Museum Studio

This session featured Josh Green, head of design at London Museum, and Tim Reeve, COO of V&A, discussing how the London Museum and V&A East Storehouse are redefining access, authorship, and audience connection.

For Green, the challenge at the new London Museum is clear: how to craft a space that genuinely connects with Londoners while also appealing to a global audience. This balance is reflected in the stories the museum chooses to tell, as well as its new logo.

“We didn’t offer a sanitised version of London,” he explained. “We always take a step back and go, do we have that right mix of both grit and glitter? Too much grit and it doesn't have that universal appeal… but too much glitter, it becomes inauthentic.”

Museum of London's new pigeon and poo splat logo

Museum of London's new pigeon and poo splat logo

It is a precise balancing of tone and truth, one that recognises complexity without sacrificing accessibility.

When it comes to innovation, Green argues that rather than chasing headline-grabbing technologies, it should be embedded in the process, not the product.

“If your end goal is, I'm going to do this super innovative thing using this technology that no one else has ever used before… I don't think the end goal will ever be as good as going, let's talk about the story that needs to be told.”

Green highlighted the need to look beyond the cultural sector, drawing lessons from the wider attractions industry to improve museum storytelling.

Meanwhile, the V&A East Storehouse was born out of a logistical need when its previous storage space was scheduled to close. Instead of a typical storage space, the team created a radically open space, allowing visitors to wander among the collection.

“Visitors have to work quite hard at the Storehouse,” Reeve said, “but they are enjoying just not being told what to do.”

The aim is to evoke wonder through scale and theatricality—an “oh my god” moment driven by the magnitude and proximity of objects, not digital overlays.

View of Weston Collections Hall, which features over 100 mini curated displays, at V&A East Storehouse. Image by Kemka Ajoku for V&A

View of Weston Collections Hall, which features over 100 mini curated displays, at V&A East Storehouse. Image by Kemka Ajoku for V&A

The Storehouse's design emphasises its industrial philosophy with raw, functional materials, highlighting its authentic working space and inviting the public into normally hidden areas.

Both institutions prioritised community engagement in development. At V&A East, local groups influenced design choices, tackling the view that museums aren’t for locals. By involving the community, they aimed for access and ownership.

Across both projects, innovation is about rethinking collections, empowering audiences, and designing honest, inspiring experiences.

Winners of the Exhibit - Culture award, sponsored by Museum Studio

1st place: Of the Oak at Kew Gardens

2nd place: Uzbekistan Pavilion – Expo 2025 Osaka with ATELIER BRÜCKNER

3rd place: Portlantis by Kossmanndejong

Innovation in retail & dining, sponsored by Lumsden

Hosted by James Dwyer, principal at Lumsden, this session explored how retail and F&B have evolved from secondary spend to central storytelling tools, with perspectives from Karl Durrant of Warner Bros. Discovery and Anne-Marie Hoogerwerf Hospes of the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

Durrant traced the expansion of Warner Bros.’ IP-led retail strategy, from the original Studio Tour in 2012 to standalone Harry Potter flagship stores in New York, Chicago, Harajuku and soon Shanghai.

Growth, he said, has been deliberate. “You cannot just take your offer and cram it into a market and expect it to work.” Success lies in balancing localisation with brand DNA – a “fine tightrope” between authenticity and commercial performance.

For Warner Bros., retail and dining are not add-ons. “The retail and the F&B in our tour spaces are definitely an extension of the experience.”

The Harry Potter Store New York

The Harry Potter Store New York

Product, service, and environment constitute the core pillars: exclusive and seasonal merchandise, staff who are part of the fandom, and immersive environments designed for superfans and casual visitors alike.

Importantly, if products are available online, stores must answer a straightforward question: what is the reason to visit?

Hoogerwerf Hospes provided a museum perspective as the Natural History Museum Denmark prepares to unify its collections under one roof.

“Retail and F&B are no longer optional extras. They are core touch points.” Commercial spaces, from a botanical plant shop to a new restaurant and café, are designed as mission-led extensions of the museum experience.

Authenticity and profitability, she argued, are not mutually exclusive. A clear “red thread” rooted in institutional purpose guides decisions, ensuring retail and dining feel emotionally resonant rather than merely transactional.

Sustainability underpins that strategy: “It is the guiding lens through which we design our entire commercial offer.”

Across various brands and cultures, the message was clear: experience is the key differentiator – and the main reason to come back.

Winners of the Retail & Dining award, sponsored by Lumsden

1st place: Haunted Mansion Parlor from Walt Disney Imagineering

2nd place: dan pearlman's Loop5 Retailtainment

3rd place: Dassai Blue Sake Brewery from Local Projects

Creating goosebumps: innovation in immersive experiences

What does it take to create a truly immersive experience in 2026?

For Damian Norman, director of immersive entertainment at Excel London and Immerse LDN; Christian Lachel, chief creative officer at BRC Imagination Arts; and Kate McConnell, senior creative director at THG Creative, the answer begins with responsibility.

“If you think about the responsibility of whatever you are producing… you have to treat that responsibility as sacrosanct,” said Norman.

Audiences are investing time, money, and expectations. In return, creators have a duty to deliver something beyond the everyday. “I think you have a duty to your audience to create goosebumps… If you can elicit those emotions, where they really feel something, and they remember something, then you’re doing something quite real.”

Emotion was the common thread throughout the session.

For Lachel, the strongest experiences “celebrate the world of the audience.”

Instead of starting with spectacle or technology, creative teams should begin with the audience’s heart and work outward, finding the hooks that spark connection and a sense of magic grounded in meaning.

The Formula 1 Experience at Immerse LDN

The Formula 1 Experience at Immerse LDN

That long-term thinking is also vital for the sector's health. Pursuing short-term gains or underdeveloped ideas that fail to generate ROI can undermine trust in immersive as a whole.

“We’re here for the long run as an industry,” Lachel said, advocating for depth, craftsmanship, and sustainability rather than quick profits.

McConnell brought the conversation back to fundamentals. While designers aspire to think outside the box, she argued that the “box” – the business case, the audience definition, the operational parameters – must first be clearly established. Only then can expectations be intelligently subverted.

She also emphasised the ongoing tension between “lean-in” and “lean-back” entertainment: highly participatory formats such as escape rooms versus more passive, contemplative experiences.

The sweet spot, the panel agreed, lies in understanding when to ask audiences to engage – and when to let them simply feel.

Ultimately, innovation in immersive experiences isn't just about scale. It's about creating moments that stay with you; the kind that give you goosebumps long after the lights go down.

Winners of the Immersive Experience award

1st place: Secret Cinema's Grease: The Immersive Movie Musical

2nd place: JOHN WICK EXPERIENCE Las Vegas

3rd place: Pixar Adventurous Journey at Shanghai Disneyland Resort

Reimagining guest experiences through innovation, design, and storytelling, sponsored by SSA Group

Moderated by Tera Greenwood, executive vice president of brand & relationships at SSA Group, this session brought together Randi Hamilton, chief experience officer at Detroit Zoo and Abby Bysshe, chief experience and strategy officer at The Franklin Institute.

Together, they explored how cultural institutions can compete in an increasingly experience-driven market.

Greenwood said that zoos, museums, and aquariums are no longer just competing with each other. “We’re competing with escape rooms, immersive theatre, theme parks, and every other experience vying for people’s time and money.”

In that landscape, guest experience becomes a key strategic differentiator.

Wildlife Rescue Experience at Detroit Zoo

Wildlife Rescue Experience at Detroit Zoo

For Hamilton, meaningful engagement begins with understanding the community. At the Detroit Zoo, this has involved equipping staff with storytelling training so that interactions go beyond just factual interpretation.

Instead of merely sharing information about animals, teams are encouraged to craft narratives that connect emotionally and inspire action. Designing experiences, she said, is about “inviting them to the conversation. Because if we are not thinking about what's resonating, then it won't bring them back.”

Bysshe also spoke about the importance of research-led design. At The Franklin Institute, workshops with target audiences – particularly candid 4th to 12th graders – help shape exhibition content.

During the development of Body Odyssey, this process uncovered a strong interest in mental health content, ultimately influencing both the scope and focus of the exhibition.

Wondrous Space at The Franklin Institute

Wondrous Space at The Franklin Institute

Storytelling, the panel agreed, extends beyond the gallery floor. Retail and food and beverage areas are powerful touchpoints that can reinforce an institution's mission when designed with narrative intent. These moments contribute as much to perception as the core exhibits themselves.

Crucially, guest experience is not confined to a single department. As Bysshe put it, it spans the entire organisation – from maintenance standards to the warmth of a greeting at the door. When viewed holistically, experience becomes culture, and culture becomes the reason visitors return.

Winners of the Guest Journey award, sponsored by SSA Group

1st place: Musa Guide

2nd place: Attractions.io's GX Pulse

3rd place: SmartPay

Bringing main character energy: innovation in storytelling, sponsored by Blue Telescope

Moderated by Blue Telescope's Judith Zissman, this session explored how attractions can place guests at the centre of the narrative.

“Guests, in my opinion, have gotten away from reading plaques... They don't wanna read the story. They wanna be the story,” said Therrin Protze, chief operating officer at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex.

With live rocket launches next door and multi-use programming such as concerts that draw in new audiences, Protze spoke about the importance of creating experiences that spark conversation long after visitors leave. “How do you get them talking all the way home in the car about what they learned, but also had fun doing it?”

At Legoland, that philosophy is foundational. “It very much is the ethos of a Legoland park is putting your guests… as the main character, the main player in their adventure,” said Rosie Brailsford, creative director, Merlin Entertainments.

From role play that extends into retail to a new Orlando coaster where riders design their own rockets, the brand builds on the imaginative play children already enjoy at home.

Legoland's Galacticoaster concept

Legoland's Galacticoaster concept

Steve Sheldon, managing partner at EPIC Entertainment Group, highlighted the appetite for deeper participation across live and touring experiences:

“If you give them the opportunity to go deeper and to immerse themselves further and to participate more, I think we've found there are very few limits to what people are willing to do.”

At the same time, audiences vary in how far they want to lean in, making choice and flexibility essential.

The panel also addressed the pressure to eliminate “dead space” and digitise every touchpoint. “We really find that combining physical and digital... helps when people use their hands... letting technology support the experience versus dominate the experience,” said Zissman.

Throughout projects and sectors, one theme stood out: story first. Technology improves, but emotional ownership – that sense of main character energy – is what keeps guests coming back.

Winners of the Storytelling award, sponsored by Blue Telescope

1st place: The Cortège

2nd place: Felix & Paul Studios' Interstellar Arc

3rd place: Disney Tale of Moana

Bringing a dark ride to life: innovation in immersive attractions - sponsored by Christie

With moderator Ernest Bakenie, senior director of sales & business development for themed entertainment at Christie, this session unpacked the creative and technical thinking behind Ghostly Manor, Paultons Park’s new interactive dark ride.

Built on the site of a former 4D cinema, the project faced a significant constraint: footprint. Transforming a compact space into a fully realised dark ride required inventive design.

Lagotronics’ Gameplay Theatre system enabled a longer, more layered attraction within the available envelope, maximising both dwell time and replay value.

Interactivity sits at the heart of the experience – but without alienating guests. “There's no minimum score you have to get. And as people leave the ride, they shouldn't feel frustrated,” said Lawrence Mancey, marketing and technology director at Paultons Park.

The goal was to find “that sweet spot of something that is easy to enjoy but still rewarding to come back.” Competitive scoring encourages repeat rides, with some guests even sharing tips online to boost high scores.

For Mark Beumers, CEO of Lagotronics Projects, intuitive design is critical. “When people enter, they have to immediately understand what to do.” Learning curves that stretch across multiple scenes risk diminishing immersion and enjoyment.

Technology choices were equally deliberate. The ride blends projection media with physical sets, avoiding an overreliance on screens.

“It was something that we were keen to be cautious of… that we weren't just throwing kids back in front of screens again,” Mancey said.

Bakenie reinforced the need for layered approaches: today’s guests are sophisticated, and true immersion requires a careful blend of media, hardware and scenic design.

Looking ahead, modularity and adaptability are emerging trends, as content updates and variable guest experiences become more accessible. As Beumers put it, “immersion is the keyword”, and advancing technology is helping parks of all sizes deliver it.

Winners of the Immersive Attraction award, sponsored by Christie

1st place: Ghostly Manor at Paultons Park

2nd place: “Walt Disney – A Magical Life” Audio-Animatronic

3rd place: RPM Raceway's Kart Klash

Designing attractions: innovation in blue sky, sponsored by FORREC

This session brought together Henry Kim, creative director at FORREC, and Virginie Valastro, producer at Moment Factory, to explore how creativity, emotion, and emerging technology are shaping the next generation of attractions.

“The more tech-driven the world gets, I think the more we crave something that we can actually feel… [Wooden roller coasters] are making a comeback, not because they're super high tech, but because they're visceral and emotional,” said Kim.

He highlighted personalisation and discovery as key drivers of repeat engagement, drawing parallels to platforms like Spotify and Netflix that adapt to user behaviour.

FORREC worked on the pre-show for Niagara Takes Flight

FORREC worked on the pre-show for Niagara Takes Flight

Valastro stressed the importance of extending experiences beyond the physical space:

“I think what is underdeveloped at the moment is how we can embark on that journey before and after once we leave the experience… creating new environments that you join, and you relive the experience differently digitally.”

She also warned against overreliance on past successes, noting that “creativity is becoming very fragile… It does take effort, risk, uncertainty… and having that space to allow creativity to continue to evolve and not fall into the trap of just refreshing older ideas.”

Both stressed that blue sky thinking is not just a starting point.

“Designing the what if – not letting an idea slow you down. Giving those Blue Sky ideas that time and the permission to exist long enough to see where those ideas might take us,” said Kim. “Blue sky isn’t a phase at the beginning; it can happen throughout the entire process,” he added.

Valastro shared how projects like Curiosity Cove span years, prompting continuous reflection: “Are we creating the right emotion? Are we using the right tools?”

Curiosity Cove by Moment Factory

Curiosity Cove by Moment Factory

Technology, including AI, was positioned as a tool rather than a driver. “AI can...give rapid outcomes and ideas, but once you get it to iteration, that is where artists are essential… AI cannot support that interaction yet,” Valastro said.

Kim agreed: “Technology shouldn’t be driving, whether it’s brainstorming or the actual development or planning. AI is always a tool.”

Both also highlighted wellness and calm as emerging priorities. “Our industry has spent a lot of time focusing on adrenaline and spectacle, but we haven’t designed enough for calm, for an emotional recharge,” said Kim.

Across forests, gaming, transport hubs, and immersive theatre, the focus remains on connection: “It won’t be about technology or scale. The most successful attraction will be how it connects, or resonates, with the guests."

Valastro concluded: “The guests are at the centre of everything that is delivered. Tech, story – all revolves around the moments we are creating.”

Winners of the Blue Sky award, sponsored by FORREC

1st place: The Giant

2nd place: AccessPro from Etholle Holmes

3rd place: Porviva's Magic Carpet

Innovation in accessibility

Kees Rijnen, strategist at Efteling, and Giacomo Bosso, product development manager at Vekoma Rides, presented the groundbreaking seat-on-wheels concept, aiming to transform accessibility in theme parks.

Traditional solutions often isolate guests with disabilities: separate queues, missed pre-shows, and transfer seats that limit choice and separate groups. Rijnen and Bosso wanted a solution that keeps the whole party together before and during the ride.

“We are not only helping those with a disability. We are also helping the group of people visiting the park with them… the percentage of people that you are impacting is much larger than the actual number of single guests with the disability,” said Bosso.

Rijnen added: “Inclusive design or design for all benefits everyone… It’s about hospitality. It’s about feeling welcome, appreciated, and about being seen.”

Left to right: Kees Rijnen (strategist Efteling), Anne-Mart Agerbeek (CEO Vekoma Rides), Har Kupers (chairman - Vekoma Rides), Joni Latour (project manager Vekoma Rides) and Femke van Es (manager society, communication & environment Efteling) blooloop.com

Left to right: Kees Rijnen (strategist Efteling), Anne-Mart Agerbeek (CEO Vekoma Rides), Har Kupers (chairman - Vekoma Rides), Joni Latour (project manager Vekoma Rides) and Femke van Es (manager society, communication & environment Efteling) blooloop.com

The solution is a ride-compliant seat mounted on a self-balancing mobility platform. Guests transfer into the seat upon arriving at the park entrance, then explore the park freely. The seat connects directly to ride vehicles, reducing operational downtime while allowing families to enjoy attractions together.

Development involved close collaboration with guests with disabilities alongside engineers, ensuring that both practical and emotional needs were addressed.

Although the technology exists, Rijnen and Bosso highlighted that commercial viability remains the main challenge. The concept is designed to be scalable and affordable, enabling parks to start with a small number of seats and expand gradually.

Rijnen framed the initiative as a call to action: “It felt to me like everybody was waiting for another to take the first step… let’s not wait for another, let’s take it into our own hands… let’s present it as our gift to the industry.”

Both speakers urged other parks and manufacturers to work together to standardise the system and lower costs, moving towards an industry where accessibility is universal rather than rare.

Winners of the Accessibility award

1st place: Accessible Multimedia Guide with Synced Audio Descriptions at Caesarea Visitor Center

2nd place: Miral Destinations' Ferrari World Esports Arena

3rd place: Deferred Happiness at Hidrodoe

Day two at the blooloop Festival of Innovation 2026

Reimagining the waterpark experience: innovation in splash

Olivia Wyrick, senior director of aquatic operations at Aquarabia Water Theme Park, shared how Qiddiya’s water park is redefining adventure, immersion, and guest interaction.

“We really respected the surroundings… some of the questions [visitors] ask, they go, 'Is this from the mountain? Did you guys actually carve this out of the mountain?' And it's like, that's how great the theming is."

The park combines traditional water park elements with adventure and sports, allowing guests to explore, pause, and simply take in the surroundings.

“The way that we've designed the park, it does allow guests to walk around and look and check out things… sit down and just really take it all in… being able just to watch other people have these amazing experiences.”

Innovation extends from queues to attractions. Interactive, engaging line experiences highlight the park’s majestic mountain setting, while Ascent, the restaurant atop the ride tower, offers a first-of-its-kind dining perspective.

Wyrick also highlighted the surf lagoon, developed in partnership with Endless Surf: “Bringing surf into a waterpark is one thing, but bringing in really top technology that can cater to beginners to experts will really put surfing on the map here in the region.”

Other technological innovations include WhiteWater’s new tube concepts, which allow guests to ride without getting wet, and Sub Sea Systems’ Aquaticar, a fully submersible family ride with bubble-propelled vehicles and integrated communication systems.

“It’s been such a great project to work on… they have put a lot of time, effort and love into the tech, the safety precautions and continuous oxygen supply,” Wyrick said.

Her guiding philosophy is perfection. “We want to get everything right for our guests and our colleagues.”

Looking ahead, Wyrick envisions waterparks embracing adventure, diversity, and community. “The more experiences family and friends can have together, the bigger the win… bringing these elements together creates communities for repeat visitation and sparks interest in young kids.”

This approach positions Aquarabia not just as a waterpark but as a destination that combines thrill, technology, and connection.

Winners of the Splash Award

1st place: Les Abysses de Lumière at Aquascope by Moment Factory

2nd place: ProSlide HIVE

3rd place: VVater Beach at Steyn City

The power of play: innovation in brand realisation

Renae Brown, associate manager of location-based entertainment for EMEA at Hasbro, and Tom Lionetti-Maguire, founder and CEO of Little Lion Entertainment, discussed the challenges and opportunities of transforming gaming IP into immersive, playable experiences.

Brown highlighted the complexity of adapting Dungeons & Dragons, which she said is one of Hasbro's more challenging IPs to bring to life.

“We begin by looking at the core fundamentals of how it's traditionally played at home. And then we ask, how do we bring those fundamentals to life in a way that can't be replicated at home?”

For D&D, this involved combining linear and non-linear storylines and creating set pieces that added theatricality and immersion beyond the tabletop.

Lionetti-Maguire spoke about the respect for beloved IPs. “These games, these brands, they’re hallowed ground for many, so you’ve got to come in with a love and respect for it to begin with.”

He said that with open-world IPs, “less is more with the big worlds,” advocating for focused storytelling within a defined segment of the universe.

Pac-Man Live Experience

Pac-Man Live Experience

Little Lion’s Pac-Man Live experience in Manchester illustrates the balance between accessibility and challenge.

“With Pac-Man, it’s one of the oldest video games… the challenge was how do you blow it up and bring it into the real world." The team created new levels that escalate in difficulty, ensuring each session is unique while preserving the video game’s emotional arc.

See also: Little Lion Entertainment & the next evolution of immersive gaming

Brown highlighted the importance of social play. “When you're playing as a group, failure becomes part of the fun. Any punishment should be playful, not punishing.” Experiences like Monopoly LifeSize turn setbacks into enjoyable challenges, reinforcing engagement for all players.

Piloting, iteration, and adaptability are essential.

“The only way to learn how to do that is to try it… and get the data and feedback from people,” Lionetti-Maguire said. Brown added, “It’s ok to pivot based on feedback when it opens. Fixing doesn’t always mean adding more; sometimes it can mean simplifying.”

Together, they underlined that immersive gaming experiences require careful design, audience insight, and a willingness to iterate.

Successful experiences combine accessibility, challenge, and emotional resonance, not just IP presence, to create moments that players return to again and again.

Winners of the Brand Realisation award

1st place: Arcade Arena Manchester – PAC-MAN LIVE EXPERIENCE from Little Lion Entertainment

2nd place: Grease: The Immersive Movie Musical from Secret Cinema

3rd place: Lionsgate's JOHN WICK EXPERIENCE Las Vegas

Intimacy at scale: innovation in cultural immersive experiences

David Sabel, executive producer at Lightroom, and Chris Conte, executive consultant and global ambassador at Electrosonic, discussed how cultural experiences can blend scale and intimacy while ensuring technology serves storytelling.

“One of the biggest challenges for museums is hiding the technology,” Conte said, though he noted visitors are often forgiving when they see it.

Sabel sees the technical elements differently: “I love the textural quality of projection… There is something more painterly about it,” he said, highlighting the opportunities and challenges of working in historic or unconventional venues.

When asked what makes immersive experiences successful, both agreed: content is key.

“You can’t have technology for technology’s sake, and expect people to stay longer than 15 minutes,” Conte said. Audio and music, they agreed, complete the narrative, creating immersive atmospheres that resonate emotionally.

Conte cited the WWI Museum, where media alcoves create intimate, personal experiences that scale effectively to larger spaces.

National WWI Museum and Memorial: Encounters Exhibition

National WWI Museum and Memorial: Encounters Exhibition

Trends include AI, which Sabel uses selectively for tasks like upscaling old footage, while remaining committed to human storytelling.

“We try to remain open, but still believe in the power of human storytelling and connection,” he said. He also noted a rise in brands creating immersive experiences, with more permanent installations appearing beyond traditional attractions, including municipal and public spaces.

Challenges remain significant. For Conte, managing client and audience expectations is critical: Hollywood sets a high bar, often beyond typical budgets.

For Sabel, operating as a startup in an emerging market requires balancing audience engagement, pricing, and quality. “It is a kind of new form… somewhere between exhibition, documentary, film, event and theatre… It has the ability to offer an experience which is both incredibly intimate and also epic,” he said.

Sabel emphasised the importance of consistency: “If someone goes to what they see as a sort of new type of experience and they have a less good experience, then it makes them more wary to go and see maybe a better one… We’re trying to keep the quality very high.”

Conte concluded: “People want three things. They want to be entertained, educated, and impressed. And if you can meet those three elements in cultural museums and exhibits, I think you’ve achieved that goal.”

The session highlighted that technology should never overshadow storytelling; intimacy, content, and quality stay central to successful immersive cultural experiences.

Winners of the Immersive Experience - Culture award

1st place: teamLab Phenomena Abu Dhabi

2nd place: ART MASTERS: A Virtual Reality Experience from ACCIONA Cultura

3rd place: Balloon Museum

Innovation in family experiences

Andy Fastman, senior vice president, and Greg Senner, vice president of creative development at Huitt Zollars, explored how creative vision and operational strategy must align to deliver attractions that resonate and endure.

Guest expectations have risen sharply, while attention spans continue to shrink. “Getting kids to look up from the phone is almost impossible,” Fastman said.

Rather than resisting that shift, the opportunity lies in creating app-based and experiential layers that draw guests into the story. Escapism, he argued, has become more important than the activity itself.

For Senner, the key is worldbuilding with agency. Attractions must move beyond passive consumption: “The guests become the characters.”

That requires cultural sensitivity too — from language and humour to queue design and visual symbolism — ensuring experiences feel authentic and appropriate in every market.

SeaWorld Yas Island, Abu Dhabi - SeaSub

SeaWorld Yas Island, Abu Dhabi - SeaSub

Monetisation is also evolving. With ticket sales often covering operating costs, secondary spend is critical. But retail and F&B must feel immersive.

Fastman highlighted the power of the “hero’s artefact” — a story-driven take-home item that deepens engagement. When integrated well, Senner added, selling a product can actually enhance satisfaction.

Repeatability is essential, with variability and futureproofing built into the design from day one.

At Huitt Zollars, innovation extends beyond storytelling. Early collaboration between creatives, architects, operators and fabricators reduces risk and ensures operational success. “We’re not a vendor, we’re a partner,” Senner said, emphasising long-term involvement from ideation through post-occupancy.

Ultimately, technology is a toolm not the driver. “Don’t do a VR experience because you have VR,” Senner said.

In a fast-moving market, the most successful projects will be those that combine compelling stories, operational intelligence and meaningful guest connection.

Winners of the Family award, sponsored by Huitt-Zollars

1st place: SeaWorld Yas Island, Abu Dhabi: SeaSub

2nd place: “Crocodile Island” at Suntago Water World from CSB - Creative Studio Berlin GmbH

3rd place: Legoland Shanghai Resort Creative World

Storytelling and spectacle: innovation in spectacular

Anna Warnecke, CEO of Kynren, and Grant Reichardt, director of business development at Aerial Illuminations, explored how spectacular experiences must move beyond visual impact to create lasting emotional resonance.

For Warnecke, the heart of any large-scale show is the feeling it leaves behind. “We know that the story is really important, but the name of the hero we may forget… what we will remember is the emotion that we had when we saw it.”

At Kynren, that emotional connection not only drives audience loyalty but also fosters civic pride in the Northeast of England, rooting spectacle in place and identity.

Kynren, the UK's historical theme park

Kynren, the UK's historical theme park

Reichardt also spoke about the importance of tapping into what local audiences care about. In Minneapolis, Aerial Illuminations collaborated with the Prince estate to create a drone portrait of the artist for a moment that resonated deeply with the community.

Drone technology, he said, has evolved from novelty to a nuanced storytelling medium. The goal is not for audiences to ask, “How did they do that?” but to walk away feeling exhilarated and moved.

Both speakers said that technology must serve the story. At Kynren, drones, pyrotechnics, live actors and animals are blended seamlessly to heighten, not overshadow, the narrative.

In a tighter economic climate, families are more selective about where they spend their leisure budgets. Passive viewing is no longer enough. Today’s audiences expect immersive, emotionally rich experiences that bring them closer to the action.

Meanwhile, Reichardt noted growing demand for seasonal spectaculars, particularly around Christmas and Independence Day, showing how timely, culturally relevant content can further deepen engagement.

Winners of the Spectacular award

1st place: Symphony of the Green Island, Cát Bà by Sun Group, Laservision & H2O Events

2nd place: Leva's Outdoor Kinetic Sculpture for Puy du Fou

3rd place: Under The Midnight Rainbow from ECA2

Horror unleashed: innovation in thrills

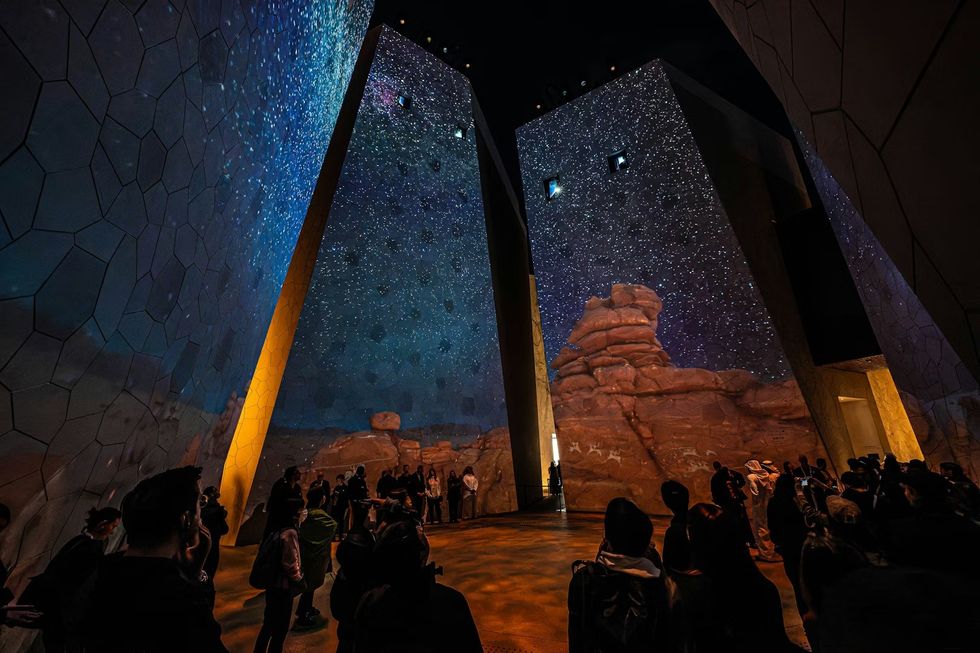

Kim Scott, general manager of Universal Horror Unleashed in Las Vegas, described the year-round attraction as an evolution of Halloween Horror Nights, with four haunted houses connected by immersive themed zones, alongside bars, dining and live entertainment.

Unlike a traditional theme park event, guests are not locked into a linear path. “Our guests get to curate their own horror experience… guests want to control their own journey.”

Visitors can spend hours exploring scare zones, interacting with characters like Jack and Chance, who are deeply rooted in HHN lore, or simply enjoy themed food and drink without entering the houses at all. Some guests even begin the evening observing from a bar before upgrading to experience a maze.

Universal Horror Unleashed - 'Texas Chainsaw Massacre' haunted house

Universal Horror Unleashed - 'Texas Chainsaw Massacre' haunted house

The attraction leans into Universal’s horror heritage, from classic slasher films showcased in the Kill Vault to modern Blumhouse properties and original IP such as Scarecrow: The Reaping.

Seasonal overlays, including a Krampus holiday experience, keep content fresh for repeat visitors and help drive local and sports-tourism traffic.

Food and beverage is central to the storytelling. The Boiler Bar growls and erupts with steam, Rough Cuts offers macabre quick service, Jack’s Alley Bar immerses guests in carnival chaos, and the Premier Bar, which is styled as a grand movie theatre, hosts character-driven dining moments.

A second-tier “Fraidy Cat” ticket allows access to entertainment and F&B without the haunted houses, reflecting guest demand for flexible participation.

Looking ahead, Scott sees device-driven enhancements and deeper sensory immersion as key trends. The ongoing challenge? Delivering more intense, up-close thrills while staying true to the brand by continually listening and evolving with the fans.

Winners of the Thrills award

1st place: Ghost Boat at Dells Boat Tours by Moment Factory

2nd place: Spike Add-ons from Maurer Rides

3rd place: Yas Waterworld, Yas Island, Abu Dhabi

Nostalgia, personalisation and repeatability: innovation in game on

This session explored how operators are blending emotional connection with smart technology to keep guests coming back.

Mario Centola, executive vice president & chief operating officer of international operations and worldwide franchise development at Chuck E. Cheese, shared how the brand tapped into nostalgia with the launch of adult-focused ‘Chuck’s Arcade’.

Simply shortening the name to ‘Chuck’ — a familiar childhood figure for many — boosted sales without changing the games themselves. The emotional connection did the heavy lifting, proving the power of brand memory.

Brent Bushnell, co-founder of DreamPark, expanded on nostalgia through the lens of mixed reality.

“The fun part is being able to sort of step into the worlds you might have nostalgic awareness of, but now be the character that you used to just control remotely."

Chuck's Arcade

Chuck's Arcade

For DreamPark’s portable VR theme park, that means intuitive interfaces and minimal onboarding. Guests are often new to VR or playing in unfamiliar outdoor environments, so simplicity is essential to reduce friction and maximise immersion.

Accessibility and scalable challenge were recurring themes. Rick Briggs, CEO of FuzionGamz and Attractions, emphasised that experiences must allow everyone to succeed:

"Everybody should enjoy the success and the reward of completing the challenge and getting out and winning the game... You want to leave there feeling successful.” Whether seven or 20 years old, guests should feel empowered rather than excluded.

Lowering barriers to entry not only broadens appeal but drives repeat visitation.

Centola summed up the commercial opportunity: "Repeatability and personalisation, they kind of go hand in hand. If you can tailor an experience for someone, they're more apt to enjoy it, and then they're more apt to come back."

With falling software costs and AI-driven tools enabling faster content updates and customisation, the panel agreed that the future of “game on” lies in delivering emotionally resonant, personalised experiences that feel fresh every time.

Winners of the Game On award

1st place: Miral Destinations' Ferrari World Esports Arena

2nd place: Arcade Arena Manchester – PAC-MAN LIVE EXPERIENCE

3rd place: Arcade Battle Experience by Beat The Bomb

From awareness to attendance: innovation in marketing

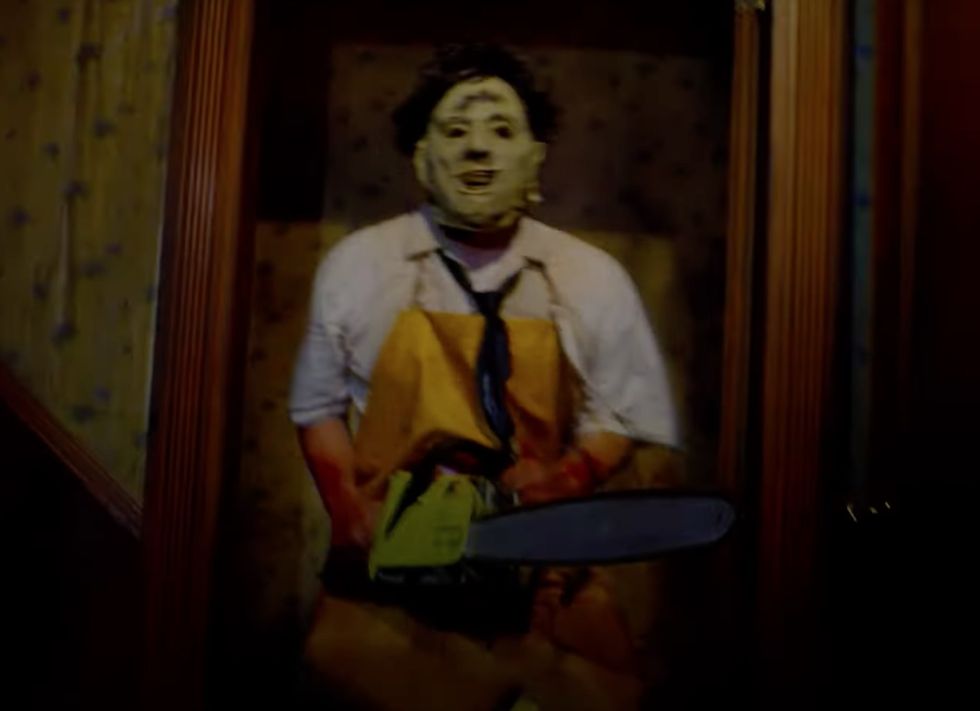

At Area15, marketing is no longer about promoting a single attraction. It’s about building a destination and a community. Chief marketing officer Amy Naples said that today’s strategy centres on connection:

"We really believe human connection and building community is something that people are really craving right now... I think it's a balance between putting your phone away, we've gotten the selfies, and let's really just be in the moment and immerse yourself in the experiences."

Rather than pushing individual experiences, the team markets the ecosystem. Guests may arrive for one headline attraction but discover an entire campus of art, events and entertainment.

Close collaboration with tenant partners ensures brand alignment, while the internal “hospitality and vibe department” works hand in hand with marketing to help guests curate the best visit for their group.

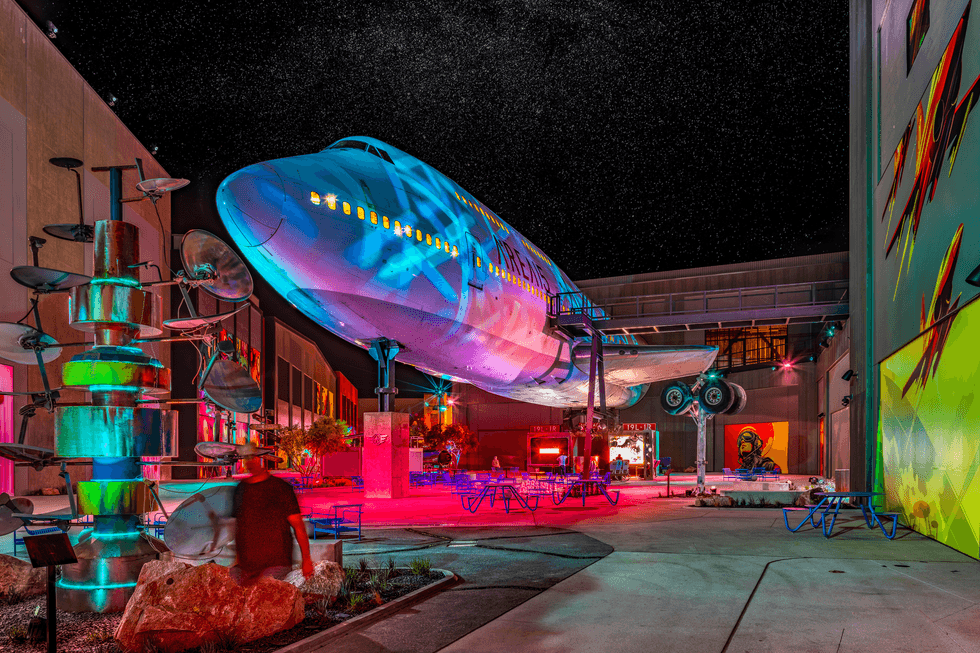

Area15

Area15

Seasonal programming plays a key role in driving repeat visitation, from large-scale rave-style events to family-friendly activations and free community showcases for local artists.

For tourists, the challenge is getting them off the Las Vegas Strip — once they arrive, word of mouth becomes one of the most powerful tools. Organic social content generated by guests is, she said, often the “best marketing that money can’t buy.”

Area15 has been an early adopter of AI, particularly in curation and trip planning. Partnerships with online travel agencies and optimisation for AI-powered travel bots ensure the destination appears at the right moment of intent.

However, Naples stressed the importance of balancing technology with creativity and authenticity.

As immersive experiences become the norm, the challenge is cutting through rising marketing costs, staying ahead of AI-driven trip planning, and clearly communicating an ever-evolving campus, while still leaving space for curiosity and discovery.

Winners of the Marketing Award

1st place: SeaWorld Yas Island, Abu Dhabi – Draw Me the Sea

2nd place: San Diego Lego-Con at San Diego Comic-Con 2025

3rd place: La Fenêtre Immersive sur le Futuroscope by DigitaLandmarks.

Innovation in sustainability

During this session, blooloop's Ruth Read and Rachel Read highlighted a few reasons to be cheerful.

Since blooloop first launched greenloop in 2021, we have seen sustainability become 'business as usual'. Key evidence includes the fact that companies are shifting to more subtle communication styles to influence sustainable behaviours.

For example, FamilyMart's Namidame, SaaS PERS phygital rewards and incentives, and Photo Ark: Animals of Earth, which connects people with their 'animal counterpart'. Also, sustainability measurement is becoming more mainstream, and we're seeing a lot more reporting.

Companies are embedding sustainability into their core business plans and values. We're seeing this in a few ways: companies are hiring in-house full-time sustainability professionals, mega corporations like Disney are integrating sustainability from the very beginning of projects, and companies are investing in sustainability R&D.

The other really great reason to be cheerful is that innovative collaborations are happening more and more, with companies thinking outside the box across sectors to contribute to various UN SDGs.

Epic Waters indoor water park in Texas

Epic Waters indoor water park in Texas

Examples include the Epic Waters project, intentionally built to be an asset to the community, White Cube and its regenerative community art, and the Florida Conservation and Technology Center, a collaboration between Tampa Electric, the Florida Aquarium, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Tampa Electric’s Big Bend Power Station circulates water from Tampa Bay for cooling, then sends the water flowing clean and warm back into the Manatee Viewing Center for manatees in winter.

They also explained that the team has listened to feedback on the greenloop event and understands that staying updated on sustainability can sometimes feel overwhelming. Moving forward, instead of an annual conference, we're moving to a monthly newsletter paired with a webinar and online meetup.

Our goal is simple: to deliver a smaller, more regular dose of inspiring, positive action and practical content that gives you a much-needed boost and keeps the greenloop community thriving all year round.

We hope you find this helpful and would value suggestions and feedback.

Winners of the Sustainability Awards

1st place: MAGIC FX ECO2JET

2nd place: Conservation in Action: Houston Zoo's Sustainable Operations

3rd place: Lookout Cay at Lighthouse Point

Best in Show and Public Choice Awards at the blooloop Festival of Innovation 2026

Best in Show goes to Of the Oak, created by Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, with Marshmallow Laser Feast.

Attendees at the Festival of Innovation could view all of the award entries and vote for their favourite.

The Public Choice Award winner is Symphony of the Green Island, Cát Bà from Sun Group, Laservision & H2O Events.

Our Innovation Award website is now live. Click here to view all of the entries.

blooloop Festival of Innovation 2026 attendees can watch all sessions on demand for 30 days.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Pavilion at Expo 2025

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Pavilion at Expo 2025  Whisper Box from Losonnante.

Whisper Box from Losonnante.  Museum of London's new pigeon and poo splat logo

Museum of London's new pigeon and poo splat logo  View of Weston Collections Hall, which features over 100 mini curated displays, at V&A East Storehouse. Image by Kemka Ajoku for V&A

View of Weston Collections Hall, which features over 100 mini curated displays, at V&A East Storehouse. Image by Kemka Ajoku for V&A  The Harry Potter Store New York

The Harry Potter Store New York  The Formula 1 Experience at Immerse LDN

The Formula 1 Experience at Immerse LDN  Wildlife Rescue Experience at Detroit Zoo

Wildlife Rescue Experience at Detroit Zoo  Wondrous Space at The Franklin Institute

Wondrous Space at The Franklin Institute  Legoland's Galacticoaster concept

Legoland's Galacticoaster concept  FORREC worked on the pre-show for Niagara Takes Flight

FORREC worked on the pre-show for Niagara Takes Flight  Curiosity Cove by Moment Factory

Curiosity Cove by Moment Factory  Left to right: Kees Rijnen (strategist Efteling), Anne-Mart Agerbeek (CEO Vekoma Rides), Har Kupers (chairman - Vekoma Rides), Joni Latour (project manager Vekoma Rides) and Femke van Es (manager society, communication & environment Efteling)

Left to right: Kees Rijnen (strategist Efteling), Anne-Mart Agerbeek (CEO Vekoma Rides), Har Kupers (chairman - Vekoma Rides), Joni Latour (project manager Vekoma Rides) and Femke van Es (manager society, communication & environment Efteling)  Pac-Man Live Experience

Pac-Man Live Experience  National WWI Museum and Memorial: Encounters Exhibition

National WWI Museum and Memorial: Encounters Exhibition  SeaWorld Yas Island, Abu Dhabi - SeaSub

SeaWorld Yas Island, Abu Dhabi - SeaSub  Kynren, the UK's historical theme park

Kynren, the UK's historical theme park  Universal Horror Unleashed - 'Texas Chainsaw Massacre' haunted house

Universal Horror Unleashed - 'Texas Chainsaw Massacre' haunted house  Chuck's Arcade

Chuck's Arcade  Area15

Area15  Epic Waters indoor water park in Texas

Epic Waters indoor water park in Texas

Rendering of the Explorers Eatery, courtesy of Hapstak Demetriou

Rendering of the Explorers Eatery, courtesy of Hapstak Demetriou Rendering of the Explorers Eatery, courtesy of Hapstak Demetriou

Rendering of the Explorers Eatery, courtesy of Hapstak Demetriou