Kew Palace, one of the six sites looked over by independent charity Historic Royal Palaces, is most famous as the former home of King George III, who reigned from 1760 – 1820.

Once a happy summer home for his large family, the country’s smallest royal palace took on more sombre associations when it became the King’s hideaway; a place to receive treatment and recover during his famous episodes of mental and physical ill-health.

This summer, the small team at Historic Royal Palaces Kew are inviting visitors to Kew Gardens to take a step back in time and re-examine the story of King George in our new exhibition, George III: The Mind Behind the Myth.

Over 200 years after the death of the King, the time felt right to reconsider the story from a contemporary standpoint, and ask how much attitudes to mental wellbeing have changed over the last two centuries – or more importantly, how much they haven’t.

New exhibition tells the story of King George III

King George III experienced the first symptoms of ill health in the Autumn of 1788. At first, it manifested like stomach flu. This was put down to his having consumed four large pears for supper the previous evening. However, as his symptoms developed, the situation became much more serious.

The King couldn’t sleep, he couldn’t stop talking and at times he even became violent and had to be restrained. His behaviour towards family members was irrational and frightening, and close relationships were irreparably damaged.

His wellbeing wasn’t just a family crisis, however; it was a constitutional one. During this initial period of illness, arguments raged over who should take control of the Government in the King’s absence. The wording on the daily health bulletins was hotly contested, as the doctors all represented different players in the ensuing power struggle.

A Regency was narrowly avoided when the King regained his health in February 1789. Unfortunately, however, his recovery was not permanent. He was plagued by episodes of ill health throughout his life. Finally, when his youngest daughter, Princess Amelia, died in 1810, it pushed him into his final phase of illness.

After 1811, when a Regency Government was finally established and the Prince of Wales ruled on behalf of his father, King George III was never seen in public again. He lived out the rest of his life at Windsor Castle, suffering under what one doctor described as “a very great degree of derangement.”

When his wife, Queen Charlotte, died in 1818, straw was laid under the wheels of the funeral procession so that the King would not be disturbed by it. He was never told of her death, and he followed her out of the world two years later in 1820.

What was the cause of the ‘madness’?

Throughout his life, the King’s treatment by his doctors bordered on the barbaric. Psychiatry was not well understood at the time, and common treatments for the King’s condition included restraining in a chair or ‘strait-waistcoat’, leeching, bleeding and cupping.

Even now, it’s hard to know what was wrong with the King. During the reign of Queen Victoria, speaking about the mysterious illness of her Grandfather wasn’t the done thing. Later, in the 1960s, a book called King George and the Mad Business was written by Ida Macalpine and Richard Hunter.

This was the first time the diagnosis of Porphyria – made famous by the 1994 film The Madness of King George – had been mentioned, and we still hear visitors to the Palace refer to it today.

Physical or psychological?

Porphyria is the name given to a group of very rare metabolic disorders that occur when your body is unable to produce enough of a substance called haem. It’s impossible to know whether King George really suffered from this, but one reason it may have seemed like a palatable answer to the mystery is that it is essentially a physical illness that can sometimes have psychological symptoms.

Even in the 1960s, it seems it was uncomfortable to suggest that the King may have been mentally ill.

The truth is we will never be able to accurately diagnose someone who lived over 200 years ago. Nor, possibly, should we attempt to.

However, much of the evidence points to exactly that. Many of George III’s episodes of ill health appear to have been triggered by trauma, such as the loss of the American colonies or the death of his youngest daughter.

When he was at his most ill, the King called for Octavius, a son who had died years before at the age of four. His never-ending talking can also be understood as symptomatic of someone experiencing a manic episode.

All these things suggest that there was at least some sort of psychological element to his illness. Doctors today think a more likely diagnosis for King George III could be something like bipolar disorder, made worse by lack of treatment and understanding. However, the truth is we will never be able to accurately diagnose someone who lived over 200 years ago. Nor, possibly, should we attempt to.

Community collaboration

I think the more valuable element of the story lies in how people relate to it today. Mental health is such an important topic (never more so than after a year of COVID). We knew the exhibition couldn’t tell the story of King George III without shining a light on contemporary mental health.

At Kew Palace, we have noticed that when we start talking to visitors about George III and his health, they start opening up about themselves. And suddenly, you’re not having a conversation about history anymore. So much in the exhibition is relatable, even though the story we’re telling is about the Royal Family.

For example, in King’s Breakfast Room, we have a very beautiful porcelain flute on display. King George was very musical. During those last awful years at Windsor, he would console and amuse himself by playing his flute. This self-care through music and artistic expression is something that many visitors can relate to.

We wanted to make these contemporary links explicit in the exhibition. So our Communities team worked with a local group of men with lived experience of ill-health to interpret some of the historic objects in the exhibition based on their own experience.

Exhibition features advice from King George’s doctor

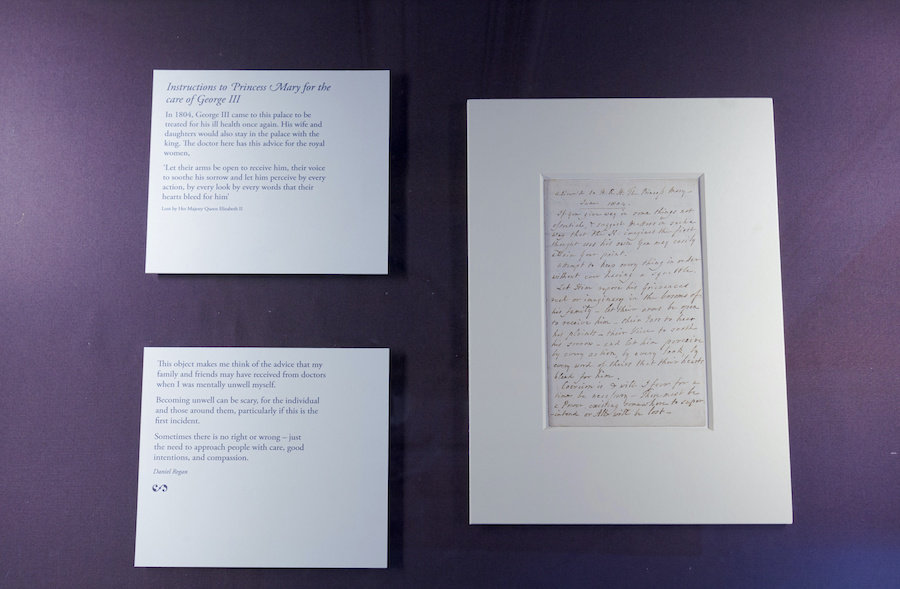

For example, one of my favourite objects in the exhibition is a letter from King George III’s doctor. This is addressed to his daughter, Princess Mary. In it, the doctor is advising how the family can best look after the King. He says, “Let their arms be open to receive him, their voice to soothe his sorrow and let him perceive by every action, by every look, by every word that their hearts bleed for him.”

A nearby community group label by Daniel Regan provides a contemporary perspective: “This object makes me think of the advice my family and friends may have received from the doctors when I was mentally unwell myself” says Regan.

“Becoming unwell can be scary, for the individual and those around them, particularly if this is the first incident. Sometimes there is no right or wrong – just the need to approach people with care, good intentions and compassion.”

Contemporary stories

On the first two floors of Kew Palace, the exhibition focuses on the story of King George III. But it’s on the top floor that we really move to thinking about contemporary mental health. In 2019, we put out an open call for objects that represent the mental health journeys of contemporary Londoners. We wanted to use objects to open up conversation and understanding for everyone. Just like we do with the historic objects downstairs.

The response was deeply personal. Our Interpretation and Conservation teams put together a fantastic display. Each object is paired with a description in the words of the lender. The accounts feature a mix of hope, heartbreak and inspiration.

One object is probably one of the last things you might expect to see on display in a Royal Palace. A stack of forty Lion bars. These represent a moment of crisis for the lender, Jane.

“When I was suffering from my first ‘bout’ of mania just over a year ago I went into my local shop and cleared their shelves of about 40 Lion Bars – at that moment I remembered that my then 29-year-old son likes them” Jane explains on her object label. “The person in the shop didn’t say anything.”

Along with our other personal objects, which you can find out more about here, the Lion bars fill the top floor of our Palace with contemporary voices, encouraging our visitors to share their own thoughts with us and with each other. When walking through the Palace it always strikes me, the contrast between George’s experience – a hidden, glossed-over, controversial illness – and the extraordinary and generous openness with which our lenders have shared their stories.

Preparing the team for the King Geoge exhibition

When we were planning this exhibition on King George III, we knew we had to prepare for a wide range of visitor responses. Visitors bring their own experiences with them, after all. That is why we wanted to give people plenty of information about what they were going to encounter in the Palace. We also wanted to signpost resources that visitors could access if they felt that they needed some support.

We worked with charities like Mind and the Campaign Against Living Miserably as well as mental health practitioners

At Historic Royal Palaces, we’re not experts on mental health. So, one of the most important elements of this exhibition was making sure we partnered with people who were. We worked with charities like Mind and the Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM) as well as mental health practitioners. This helped to make sure we were dealing with the issues in the right way. It also meant we could develop resources visitors could take away with them.

Training and talking

I wanted to make sure that we prepared our Visitor Host team at Kew particularly well. Not only could they face a multitude of different responses, but it was also important to prepare them for some challenging conversations. We also had to consider their own wellbeing and mental health.

Working in spaces that are emotionally impactful can be a really challenging thing to do every day. You don’t get to shake the experience off in the same way as you do when you’re a visitor.

The first step was to make sure we were clear in the recruitment process about the themes in the exhibition. Then, during the induction period, we spent a lot of time talking about mental health topics. Firstly, to make sure the Hosts had all the information they needed. But also just to get them familiar talking about these issues in a really open way.

One of the objects on the top floor relates to suicide. Obviously, this can be an extremely challenging topic to tackle. So we worked with CALM to deliver the same training they give to their event volunteers. This looks at the statistics, myths, and vocabulary around suicide and where to find help.

We covered Safeguarding training and made time for the Hosts to speak to some of our community participants and contemporary lenders as part of their induction. We also made sure all of our managers and supervisors for the season were qualified Mental Health First Aiders.

“You might save people with this exhibition”

After all this planning, we expected a strong visitor response. However, it is truly overwhelming how positive reactions have been to our King George III exhibition. Although some of the content is emotional and we have seen a few tears, visitors have been so supportive of our approach and vocal about how relevant and important the topic is. Especially in the wake of the pandemic.

Visitors have told us it has made them feel less alone. It has also inspired them to have conversations with friends and family about mental health. The most amazing comment, made to one of our Hosts a few weeks ago was “you might save people with this exhibition.”

To me, all of this goes to show the power that history can have; from opening up new conversations to making people think in different ways. We’ve always had this engaging, enthralling story to tell at Kew Palace. But now, by inviting more people into the conversation and by being open and sharing with our partners, our lenders, our visitors and even each other, that story has real power today.

George III: The Mind Behind the Myth is open at Kew Palace until 26 September. Top image: a shirt belonging to King George III, featured in the exhibition, courtesy of Historic Royal Palaces