Medhavi Gandhi is the founder of the Heritage Lab (2015), a digital platform connecting museums and citizens in India.

Her focus is digital and content strategy, public engagement, workshops, educational outreach and marketing. In 2019 she was a Research Fellow at the Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation/SPK), working in collaboration with ICOM Deutschland to develop a Toolkit for Museums to #EmbraceDigital.

Gandhi also has an MA in Business Administration (Communications Management) from the Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Pune (2009) and a BA (English Literature) from Kamala Nehru College, Delhi University (2007). She is the Regional Ambassador (India) for Wikipedia Art + Feminism, has been the India Coordinator for UNESCO MuseumWeek, and is the India Coordinator for Ask-a-Curator, all international activities to improve public engagement in museums through digital content.

She spoke with blooloop about Happy Hands, how this led to the inception of Heritage Lab, and her hopes for the future of the platform.

Exploring folk arts and crafts

“I started an initiative called Happy Hands way back in 2009,” she says. “I was fresh out of an MBA degree as a 23-year-old, and I started it simply because I had realized during an internship that we didn’t know much about our own folk arts and crafts and culture.

“It was always looked upon as something that our mothers would purchase or know about. It’s also because growing up in school and college we hardly had any exposure to the arts, if we were not pursuing a degree in art.”

“That prompted me to dig deeper, and to build this foundation to create public engagement with the arts. It has a focus on the youth, and young and upcoming artisans and craftspeople; the children of artisans and craftspeople who were growing up at a time similar to ours but were still waiting for opportunities to grow their traditional work.

“I would say that, in a lot of spaces, artisans and craftspeople didn’t want their children to do the same work. It wasn’t the case everywhere. But whenever we came across that, it was something that we wanted to work on.”

Happy Hands

Gandhi started Happy Hands with two of her friends. “My background is that I was a regular college kid who wanted to get an MBA and get a corporate job. It didn’t turn out like that, and my parents had their concerns. But I managed to convince them, and, in fact, my parents also became some of my first volunteers.”

Youth acceptance was immediate, she found:

“We worked with schools, we worked with colleges, and we worked with corporate houses, which was new at that point. Nobody had married corporate training and human resource activity to crafts exposure. So, we did a lot of that, and we were supported by some wonderful companies, such as Kuoni [subsequently taken over by Thomas Cook in 2015.]

“They were some of our best supporters. They took employees to volunteer in villages and invested in craft-related corporate gifting. It helped turn people’s perception of crafts around.”

She and her team also did a lot of educational programmes:

“We partnered with organisations such as Teach for India, exploring the potential of art in every space possible. That was something that led to the Heritage Lab because while working on a project, we would take a multidisciplinary group of people to a village to work, and then create exhibitions.

“One time, we thought we should do a travelling museum exhibit for Hampi, a UNESCO World Heritage site. We wanted it to be more accessible to government school children who don’t get to come on school field trips and see this wonderful place.

“So that’s how Heritage Lab started; with creating a travelling museum exhibit.”

Working with museums

At that point, they were running residencies for young artisans and craftspeople.

“We would take them to different places to understand their consumers and to understand the market. We would take them to different shops, but we would also take them to museums to understand what their art had been like in the past; what their ancestors had created, and how art got the capacity to communicate different stories at different times.

“That was the point where we started working with museums because museums are so welcoming.”

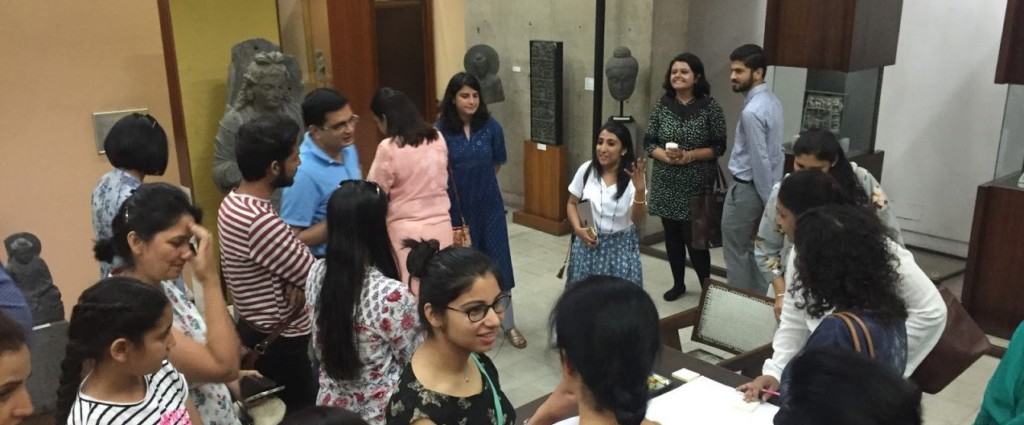

Their involvement started with physical visitor engagement, rather than digital, such as workshops for people:

“We started working with the Crafts Museum because it was a natural connect for us to explore crafts.”

Encouraging museum engagement

It was at that point, she realized that her friends working in different places still didn’t know about museums.

“Nobody would visit a museum. We do visit museums when we go to different countries, but in our own country, that’s not the case. It’s also because when we were kids and we went to the museum, it was the sort of experience where you move in a line from the entrance to the other side, without being allowed to speak or touch anything.

“I think that kind of a memory scarred a lot of people for life and put them off even taking their kids to the museum. Largely, that’s the memory of a museum for a lot of our generation.”

More welcoming spaces

Now, however, it has changed:

“Museum programming has changed over time, and museums are far more welcoming spaces, relevant to everybody, and hands-on. We began to think in terms of writing about museums, and creating fun campaigns that brought museum content into the digital space, so there is news about it.”

“If people have seen and read about exhibits online, they are then less intimidated. It was a campaign of demystification.

“The other side was, of course, to focus on teachers and education, something that Happy Hands had already been doing; working on craft resources for teachers and art in education. It was a natural progression to look at the museum aspect, and see how it could best fit with the curriculum, especially the history curriculum.”

Teachers took to it with enthusiasm:

“For history teachers, especially, there’s aren’t many great programmes to explore. It all fit together, and the transition was pretty smooth. And then Heritage Lab had its own journey.”

The Heritage Lab journey

Initially, there were challenges for the Heritage Lab in terms of engagement and making partnerships, she explains:

“It was a big thing, at first, for Heritage Lab to bring people into the museum. So, we started doing a lot of these creative inquiry workshops at museums, so that schools would come in. Side by side with these, there were global campaigns like MuseumWeek that were happening.”

“Just two or three Indian museums were participating in MuseumWeek, and they didn’t have much of a social media presence. And that’s where the audience is, of course. So if the visitor who is walking through your door is active on a certain platform, and you’re not talking to them there, there’s a disconnect.

“We started doing a lot of these social media events and campaigns to encourage museums to participate, building content for them so that there was something for the audience to consume.

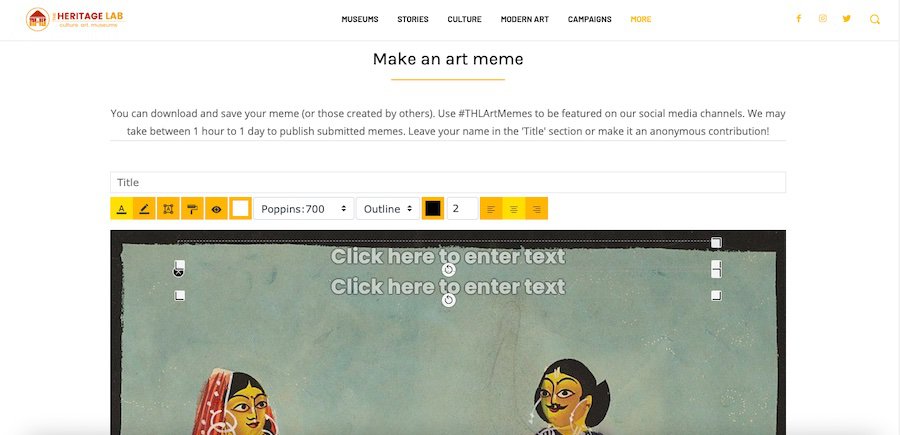

“In parallel, we were working on audience engagement by providing them with whatever content we could. Whether it was games, whether it was an online exhibit, whether it was a story, maybe a Twitter quiz. Something to spike that interest in culture again, and look at museums again.”

Information activism

“I think the big thing was bringing Wikipedia’s Art + Feminism campaign into India,” says Gandhi. “It got people interested, enabling as it did digital participation. People came to the museum. They saw what they could put up online. They were given access to museum libraries, which was unheard of. Usually, museum libraries are only open to scholars.”

“It was great to start bringing people into the museum library to record the books, to edit Wikipedia. They were learning this digital skill, and I think that got a lot of people interested. That’s information activism.

“We realised that the audience that just wants to passively consume content or information is no more. The audience now wants to participate actively in working with the museum. That’s what gave Heritage Lab its other base: we decided, OK, we want to create more of these things that the audience can actively be involved in doing.”

Visitor engagement

Before starting Heritage Lab up formally, Gandhi and her team had conducted a visitor survey:

“The survey told us why people were apprehensive about visiting museums. We shared that information with museums, and these little things like art and feminism; enabling museums to host these kinds of things, and creating campaigns and content-oriented work for them.”

It gave museums a direction, and a focus on something new they wanted to do, says Gandhi:

“It gave people a new reason to engage.”

Then came the GIF IT UP initiative, backed by Europeana:

“We decided to start making gifs using open collections and that has now sort of positioned the Heritage Lab, in a way, to help, aid, encourage – whatever we can do, to help museums’ open collections. A lot of museums have already got their collections digitised, and some of the artworks are in the public domain. But the understanding of open access is limited, not in the museum space, but in terms of the audience space.

“Because it’s the social media generation, everybody thinks you can just save the image. If it’s on Facebook, you can save and share it. So we have to, again, start working on this creator culture where we can talk about open licenses, how these can be used.

“India is a creative country. We have so many people creating so many different kinds of art, and the idea is now to let them experiment. To unlock these things for them to formally use and be inspired. The Heritage Lab is, like we say, a lab. So different experiments are happening at different times with museum objects, collections, and, largely, content.”

Giving people ownership of their heritage

The Heritage Lab project gives people ownership of their heritage, illuminating the past, and forward into the future.

“I believe that heritage is a community need,” says Gandhi. “It, therefore, needs the community to protect it and preserve it.”

Heritage is a community need… it, therefore, needs the community to protect it and preserve it

On a global scale, it is becoming increasingly clear that museums need to sit at the heart of their community:

“I think at this point, where there’s a pandemic upon us, people just need more culture and happiness and general creativity to lift their spirits.”

The Heritage Lab and COVID-19

The pandemic has driven innovation, in terms of inhabiting digital spaces.

Gandhi says:

“In India, I have seen a lot of people suddenly come up with an online presence during this time. I think that’s an innovation in terms of their approach. People are exploring new ways to engage with each other. The audience is innovating. But the museums are creating new kind of initiatives, too, in terms of programming for their audiences. It is a very interesting time.”

However, she adds:

“If anything, the digital thing has just widened the gap between museums that are not digital, and the museums that were already being innovative. But some museums had not remotely done anything, and now are coming up, doing things; and there are new sorts of creators also who are emerging. So I would say it’s a good way to start.”

Looking to the future

Of the future, she says:

“We want to be a digital platform where people who are visiting museums can share their learnings, their creations, with a wider community of people. We want to enable more creators, more people who would collaborate with museums and enable a healthy exchange on our platform. I wouldn’t say we want to become the social network for people who love culture. But it isn’t too far from the truth, because I think we need that.”

“I know for myself and a couple of my friends who are involved with the Heritage Lab that we want to be part of a community like that, which is why we want to create a space like that. Somewhere where people who go to museums can share it with other people; maybe create their own little museum walk and share it with the rest of the people. That kind of a dialogue space.

“But this is such an evolving space. So, one doesn’t know what would be a great or a better step to take next year. A lot of the things that we’ve done this year were not things that we had planned to do. It’s constantly evolving.”

The importance of social networks

In conclusion, she says:

“Yes, we want to create enough digital tools for museums to use and publish content on our platform. We want this to be a great media platform for museums, in a sense; that one media platform for all museums in India, or about objects that have something to do with Indian culture. Hopefully, we will expand around Asia, because Asian culture needs to make its space, also.

“During this time I’ve had an incredible opportunity to connect with colleagues in Singapore and Indonesia. So, I feel that maybe, some years from now, we will all collaborate and be on a common platform.

“I don’t think Heritage Lab will be that one platform, but I think we will have a role in moving towards creating one.”