In October 2011 a TiLE Forum was held in Florence, Italy. The opening session was devoted to the EXPO or World’s Fair. Robert Simpson (left), Founder Director of Electrosonic, gave an overview talk “The EXPO phenomenon” describing its origins and development through to the 21st century. The article that follows is a summary of the first part of the talk, describing the EXPOs of the 19th century.

In October 2011 a TiLE Forum was held in Florence, Italy. The opening session was devoted to the EXPO or World’s Fair. Robert Simpson (left), Founder Director of Electrosonic, gave an overview talk “The EXPO phenomenon” describing its origins and development through to the 21st century. The article that follows is a summary of the first part of the talk, describing the EXPOs of the 19th century.

It is generally accepted that what we now refer to as EXPOs had their origins in “The Great Exhibition of the Industry of all Nations”, held in London’s Hyde Park 1851. The picture below may not seem of the highest quality, but I like it because it is from a (now rather musty) book, published in 1851, that I have which lists all the main exhibits to be seen at the exhibition.

Related: Aspects of EXPO 2010 -an Audiovisual Review / Audiovisual technology: A short history of the videowall / Sound Advice from Leading Lights: The Future for Audiovisual in the Attractions Business

It has to be said that the idea of an exhibition that showed a wide range of industrial or domestic products was “borrowed” from France. However the 1851 Exhibition diffe red in scale, and the fact that it had exhibits from all round the world (rather than a single country). The “Illustrated Exhibitor” claimed that there were 17, 000 exhibitors showing a million exhibits, even though the entire exhibition was under one roof.

red in scale, and the fact that it had exhibits from all round the world (rather than a single country). The “Illustrated Exhibitor” claimed that there were 17, 000 exhibitors showing a million exhibits, even though the entire exhibition was under one roof.

The 1851 Great Exhibition attracted six million visitors in five months. It could do this for two principal reasons; one was that (with the exception of the first month when the “toffs” visited at a higher price) it offered “The World for a Shilling” (probably around £2.50 or $4 in today’s money) and because by 1851 the railway system could deliver day visitors from a distance.

Visitors in 1851 were interested in many things which resonate with us today. They were curious about the foreign and exotic, enjoying features like the “India Court”. They were interested in how things were made, and in new manufactured articles, and they wanted to see the latest technology. The showing of “Mr Henley’s Magneto-Electric Telegraph” and Thomas de Colmar’s Calculating Machine from France would have been the 1851 equivalent of seeing the i-Phone.

After 1851 there was something of a “Great Exhibition Fever” with cities round the world vying to put on the most elaborate show. Between 1852 and 1900 there were 45 International exhibitions claiming to be “Great”. Developments in this period included the introduction of separate pavilions, either to present different exhibit categories or to showcase different countries (or both). These were augmented by many features we recognize today, such as amusement attractions, water features and cultural exhibits.

An early example of an “attraction” was at the Paris Exposition of 1867, where hydraulic elevators took visitors up to a rooftop walk.

The Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia did much to emphasize how EXPOs became symbols of prestige. The organizers claimed that “In the eyes of the nations of the wo rld we have attained a rank never accorded to us before.” It seems that foreign visitors expected to see a rather backward country, but were surprised to find that in many respects the USA was ahead of Europe. The exhibition attracted 10 million visitors in five months.

rld we have attained a rank never accorded to us before.” It seems that foreign visitors expected to see a rather backward country, but were surprised to find that in many respects the USA was ahead of Europe. The exhibition attracted 10 million visitors in five months.

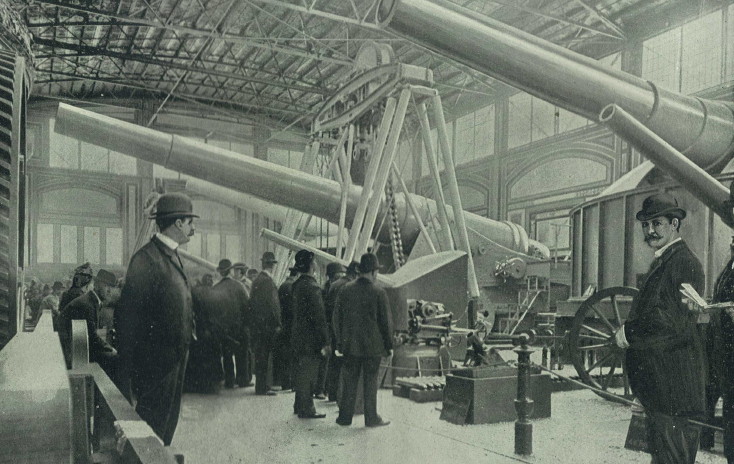

It was the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 where nearly all the trappings of the modern EXPO became evident. Apart from achieving 27 million visitors in six months, it was the first “Great” Exhibition to feature the use of electric light. It also featured what was claimed to be the “World’s Biggest Fountain”, actually a large fountain complex spread over a wide area featuring some grossly over-the-top statuary. Many visitors were fascinated by the giant gun exhibit from Krupp.

It also featured a classic EXPO “mistake” where the exhibiting country completely misjudged the public’s interest. The organizers made remarks like “the pavilion did not commend itself favourably to either the taste or the pride of the Americans”; “an exclusive place, where public hours were short”; “visitors pass but a few moments in the interior”; “Offices of the Commissioners occupied the portions of the house not open to the public”. You have guessed it, this was the British Pavilion.

It also featured a classic EXPO “mistake” where the exhibiting country completely misjudged the public’s interest. The organizers made remarks like “the pavilion did not commend itself favourably to either the taste or the pride of the Americans”; “an exclusive place, where public hours were short”; “visitors pass but a few moments in the interior”; “Offices of the Commissioners occupied the portions of the house not open to the public”. You have guessed it, this was the British Pavilion.

Another innovation at the Chicago exhibition was the Ferris Wheel, a speculative project by  George Ferris which by some accounts was late in completion, but in fact was very popular and recouped its entire investment during the run of the fair.

George Ferris which by some accounts was late in completion, but in fact was very popular and recouped its entire investment during the run of the fair.

EXPOs get very crowded, and there may be long distances to walk between pavilions. At the Chicago exhibition loud complaints were heard along the lines of:

“The fair will go down into history as the most fatiguing region of the world”.

“The visitor walked over half a mile to enter the Manufactures Building, and it was about half a mile long when he reached it”.

“No means of transport cheaper than a push chair at 75c an hour”.

Ironically a solution had been proposed to deal with the problem. Engineers Schmidt and Silsbee devised a “Movable Sidewalk” that was originally intended to go round the grounds, but it was relegated to a pier on the lake, mainly because of pressure from the friends of the push chairs. By paying five cents for a seat the “tired visitor might ride as long as he pleased”.

Schmidt and Silsbee’s idea did not die in Chicago. In 1900 L’Exposition du Siècle was held in Paris and for this French engineers re-designed the system as the “Trottoir Roulant”. This consisted of three strands, one static, one running at 4 kph, and another running at 8 kph. It was a great success and, amazingly, there are no reports of any serious accidents. Thomas Edison took a film of it in  operation and you can find this on “youtube”.

operation and you can find this on “youtube”.

The Paris Exposition of 1900 is now remembered best for the Eiffel Tower, but the whole exhibition was full of exuberant architecture. It achieved no less than 48 million visitors in six months, a record that was not to be broken until Chicago in 1934.

Paris also recorded a heroic failure. A film maker called Raoul Grimoin-Sanson anticipated by many years the major theme park ride with his “Cinéorama”. His concept was that of a simulated “balloon ride”. 200 visitors at a time would enter the “basket”, and would then see a film presented by 10 synchronized 70mm projectors, each showing images 9m (30ft) square. The show was accompanied by phonograph sound (presumably with very large horns!) and was made using a matching camera set that actually did go up in a balloon.

While the artist may have taken some liberties, there is no reason to doubt that the drawings that appeared in contemporary issues of “Scientific American” represent quite well what was going on. But from these drawings you can see that the audience are on a platform directly above the projectors, complete with their carbon arc lamps and highly inflammable nitrate film. On these grounds the authorities closed the attraction down after three days.

A reasonable conclusion is that all the main elements of what we now call “EXPOs” were in place in the 19th Century. The excitement of new ideas, the making of the same mistakes over and over again, the crowd problems, transport systems, exciting architecture, curious exhibits, and even ambitious AV systems were all there in 1900!

Note

For the enthusiast the book “The Great Exhibitions – 150 years” by John Allwood, revised and updated by Ted Allan and Patrick Reid is recommended. Published by Exhibition Consultants Ltd in 2001. ISBN 0-9540261-0-1. It is out of print but is available, e.g try “bookfinder”. As of 15 December prices were in range £50 – £200. One vendor claimed to have a new copy at £90.

Images (from the top)

1. The India Court

2. Author Robert Simpson

3. Exterior of the exhibition building that became known as “The Crystal Palace”, designed by Joseph Paxton. Sketch from “The Illustrated Exhibitor”, 1851.

4. High Tech 1851 style.

5. Sketch from “L’Exposition Universelle de 1867 Illustreé” showing the hydraulic lift attraction. Reproduced in Allwood.

6. Pictures of the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. The Horticultural Hall and an exhibit from a sewing machine manufacturer. From “The Illustrated History of the Centennial Exhibition” by James D. McCabe. Philadelphia 1876.

7. Electric light on the Administration Building, and a part of the Columbian Fountain at the 1893 Chicago Exhibition. All photographs of the Columbian Exposition from “The Dream City” published by N. D. Thompson in 1893.

8. The Krupp Guns and the offending British Pavilion, “Victoria House” in Chicago 1893.

9. The Moving Sidewalk under construction.

10. The Ferris Wheel was 250ft (76m) high and had 36 cars.

11. The Trottoir Roulant (image Wikicommons) and La Rue des Nations on the left bank of the Seine. From “Exposition Universelle, Paris 1900, Héliotypes de E. Le Deley”. Reproduced in Allwood.

12. The basket for 200 people, and projectors, Camera platform . Raoul Grimoin-Sanson’s “Cinéorama”. Drawings from Scientific American September 1900. Public domain.