by Louis Alfieri of Raven Sun Creative

As a Westerner have you ever watched an Asian film or read an epic tale and wondered about the number of characters involved in the story? Or, as an Easterner, have you ever read a book or seen a series of western films and wondered why everything revolves around a single character or action?

Myself and Amy Kole have worked as writers for both cultures and share an admiration for both narrative templates. Here, we sit down to discuss the differences between Eastern and Western storytelling structures, as well as what each says about their individual and societal viewpoints.

Insights from Eastern and Western Storytelling

LA: I have been incredibly fortunate to have the opportunity to spend the last 20 years of my life and career working as a bridge and ambassador between western and eastern cultures. I love both of these cultures deeply, and they have both become an important part of shaping who I am today.

AK: Although I’ve spent less time overseas (specifically in Japan), I agree that being immersed in the culture has not only educated me on Eastern culture, but illuminated aspects of my own culture that I had never noticed before, or it gave context to Westernized traits and expectations that hadn’t pinged my radar as different when I first moved to Japan.

LA: Both Eastern and Western culture offer insights the other does not possess, teach you lessons in a different way than the other, and each offers remarkable opportunities for the discovery of wonderful people, places, cultural assets, a way of thinking, and the combined fabric of their communities.

How does storytelling differ structurally in the West vs. the East?

AK: Even though I would say I’d absorbed a fair amount of Japanese media growing up, it hadn’t occurred to me until about a year ago when I showed two friends (both of whom have studied Joseph Campbell) Miyazaki’s Spirited Away that I realized just how different the story structure was to, say, a Disney film.

I’d watched that movie easily a dozen times. But it took viewing it through a fresh pair of eyes to realise just how much of a departure there is between a Miyazaki or a Disney film.

LA: It may not be immediately noticeable to the general public. But there are a number of noticeable differences between Western and Eastern storytelling. These differences often reflect the characteristics of their culture and society as a whole. Through these differences, we can gain an entry point and opportunity to better understand the other.

Typically, western stories focus emphasis on one central character and are often told from, or viewed around, this character’s arc. Western plot structures using a single person are often communicating the Journey of the Hero, whereby a character must endure a series of questions, challenges, and transformations to achieve an end goal.

Often these challenges will test the character’s will, moral compass, and strength – with the outcome of this journey resulting in changing, achieving, or saving something of value.

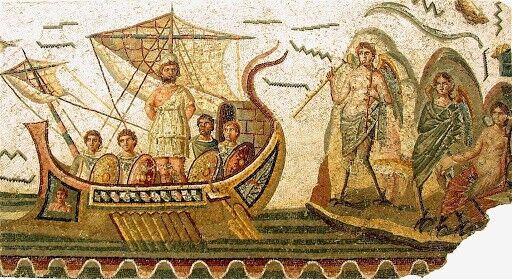

As of late in modern pop culture, this mechanism (or trope depending on your perspective) is often illustrated as saving everything on earth. Everything revolves around conflict. This story structure is a remnant of our connection to the Greeks, and stories such as the Odyssey and Iliad.

Western vs Eastern storytelling conventions

AK: In all honesty, I hadn’t thought about how The Hero’s Journey was more of a Western convention. I had thought the notion was more universal and instinctual when it came to storytelling. When I started writing for a Japanese audience, I was surprised to learn that particular story structure doesn’t resonate everywhere.

Americans, in particular, have become conditioned through narratives and Hollywood media that everything must have a “happy ending”

After all, as humans, aren’t we all conditioned to enjoy the same types of stories? Or to become moved from the same types of human experiences shown on the screen?

LA: Americans, in particular, have become conditioned through narratives and Hollywood media that everything must have a “happy ending”.

Europeans are much more receptive to a “grey” or violent ending. One where the moral to the story has been achieved, and that happiness is not dictated as the final outcome (usually a grizzly outcome for the antagonist is). The Disneyization of classic fairytales is an excellent example of this regional difference in Western storytelling.

Collectively, Westerners have a romanticized perception of the individual’s ability to overcome any obstacle. Regardless of how insurmountable it may seem. They want to imagine that with enough grit, tenacity, determination, and even a little luck that any challenge can be triumphed.

There are countless Western stories where they wrap up all of the storylines. The star-crossed lovers wind up together. The world is saved, and all of the key characters and societies live happily ever after.

AK: That doesn’t sound familiar at all! It’s true. Western stories usually focus on those “exceptions” in their own stories.

Reflections on life

LA: In Asian literature, content, and films, nobody, regardless of stature, is considered safe from the challenges of life. There is a much greater understanding of the interconnectedness of life and society as a complete ecosystem. In Japan, in particular, there is a much greater understanding and acceptance of impermanence, different perspectives on beauty, symmetry nature, and its impact on society.

This is a reflection on the power of nature to shape the people, culture, and the land, through earthquakes, typhoons, and tsunamis that have occurred through the aeons. Asian cultures often look through a lens of observing life as a chain of events, transience, states of being, and reincarnation.

This is a thread of existence through time versus being a single linear path, resulting in one single endpoint with no meaning or action to take place once that form has come to an end. Furthermore, they see an ability for one character or event in life to transfer to another and for things to carry on much more so than Westerners do.

This can be expressed in a way such as that the main character might get killed in the middle of the story. Or an epic event may take place changing the entire direction of the story. Lovers are less likely to end up together. Self-sacrifice, death, and sadness are all very acceptable story endings. The feeling of loss is welcome and comforting versus feeling depressing.

Kishotenketsu

LA: This concept can also be articulated through the four-act structure, known in Japan as Kishotenketsu. It takes its name from the names of the four different acts of the structure:

- Ki : Introduction

- Shō : Development

- Ten : Twist (complication)

- Ketsu : Conclusion (reconciliation)

AK: Although there are some considerable differences in the storytelling techniques of the two cultures, there’s at least a bit of overlap on both sides. I hadn’t seen Seven Samurai before living in Japan. I was surprised to learn how this film, which was made in Japan, has been considered the template for Western films that came after.

I’m sure I’m not the only one who thought that one of America’s claims to fame was this particular genre. But I love the idea of inspiration. Of course, that’s not to say that the original and its American remake don’t showcase the differences in our culture.

LA: Akira Kurosawa is such a visionary director. I am always inspired by his work.

What can Eastern and Western storytelling teach us about their individual cultures?

AK: On moving to Japan, it blew me away that the law didn’t necessarily enforce cooperation amongst citizens. It was a sense of collectiveness that the key behind an efficient and safe society was courtesy. Of course, this is different from American’s emphasis on individualism.

It seems like such a small detail. But now that I’m aware of it, I feel as though I can’t turn it off in my head when I’m comparing, for example, Japanese entertainment to American entertainment. Metaphors, details I hadn’t noticed before.

LA: These differences often reflect the characteristics of their culture and society as a whole. Through these differences, we can be afforded an entry point and opportunity to better understand the other. The artist Yang Liu does a great job of illustrating these dichotomies and understandings in her picture book East Meets West: An Infographic Portrait.

AK: Right. For example, Seven Samurai and its American remake Magnificent Seven follow the same setup and goal. The characters are mercenaries who take on a seemingly impossible task. Yet despite the overlap of cultural storytelling techniques that become interwoven more and more with each re-telling, the differences of the Japanese film and its subsequent American remake fall under the concept of what we’ve already discussed. It is collectivism vs. individuality.

In the original Japanese movie, the samurai hired to protect the village share feudal relations with the peasants. Despite the tensions, they coexist. The samurai are not paid money. Instead, they are provided food and shelter as they fulfil their role in this society, creating a balance. In Magnificent Seven, the cowboys work for profit.

Villains in Eastern and Western storytelling

LA: Eastern and Western storytelling utilize very different characteristics to build their heroes and enemies. In the West, the leading character is typically someone who must face an almost insurmountable obstacle. This character must build their will, is often exceptionally smart, and is in pursuit of a specific and monumental goal or solution.

In the East, stories often utilize characters whose motivation is to do something beneficial for their country, clan, and society. Rarely are these characters expressing rationale based solely on their own personal journey, emotional challenges and expanding those outwardly to others. Often self-sacrifice is expected, and that personal burdens should not be hoisted on those surrounding them.

AK: A common trope in Western stories is a villain motivated by greed and power. What can be said for Eastern villains?

LA: Many stories don’t have an actual villain but are an articulation of having misbehaved and angered nature, spirits and gods. Occasionally, there is no climactic confrontation or conflict in Eastern stories; this is a result of believing in destiny, karma, and an inherent order to things that must be followed.

It is less an issue of good and evil and more a depiction of character studies, loyalty, cause and effect, punishment for misbehaviour, and an articulation of the difficulties of life and society where the real dilemma or challenge is to learn how to find to identify what is good and worthy in life and to determine how to help it flourish. For example, the stories surrounding Buddha, and Journey to the West.

AK: That sounds about right. Sort of like how Godzilla doesn’t actually represent a fear of monsters.

Lessons from Godzilla

LA: Godzilla is a far more complex character than many people realize. As a character and IP that originates in Asia which has been embraced in the west, Godzilla offers several insights, consistent with our conversation, that might not be immediately obvious to the casual observer. The character has multiple iterations and meanings.

In Godzilla’s origin story and many subsequent films in the franchise, Godzilla represents, or is, an embodiment of nuclear holocaust, human suffering, and natural disasters combined. Further articulated is that man’s tendency towards war, interference in the natural world, and society’s indifference, lead to significant consequences. One of those being Godzilla.

The character exhibits a great deal of range over the franchise, at times expressing heroic traits, one-time vengeance, and many others the sheer power and indifference of nature.

AK: Nature has no bias. And the later instalments of Godzilla cover more than deep-seated fears of being an island nation. They also cover the significance of protocol among Japanese citizens and their government.

Behind the monster story

LA: Toho’s directors and artists are keen observers of the world around them. In films like Shin Godzilla, they are using allegory, metaphors, and literal examples of Japanese social hierarchy, etiquette, government bureaucracy, and the immense social risks presented when opposing contrary ideas to the general consensus.

Beyond the monster’s story, the creative team also explore many other topics using multiple human character arcs and social issues. For instance, corruption, pollution, warfare, global powers, etc.

Godzilla has more than thirty films and multiple series in live-action and animation over 6 decades. It is the longest-running franchise in film history. It offers many international filmmakers and storytellers the opportunity to express themselves and add to the richness of the Godzilla character universe, most recently with Legendary’s Monsterverse.

Godzilla’s story and visual influence have also inspired artists and creatives throughout popular culture, through visual and narrative art form. Most recently, in the visually reinterpreted works of the Mondo artists and becoming manifested in the Location Entertainment space in Japan at several locations.

Eastern & Western storytelling and experiential entertainment

AK: Everything we’ve discussed today, from individualism versus collectivism to heroes and villains, are all reflected in the many facets of location-based entertainment. This includes art exhibits, theme parks, retail, and dining (though the list goes on and on).

I’m excited to talk about how this is now reflected on our bread and butter–– experiential entertainment. More specifically, Louis, I can’t wait to hear your thoughts on how Eastern and Western storytelling conventions affect the guest role. The differences are illuminating. And not just as an experiential designer, but also an avid visitor to these types of locations and experiences.

Culture speaks. To become immersed in an experience that both relies on an emotional journey through an experience rooted so wholly in its society becomes among the most palatable approaches to understanding, learning, and celebrating another culture.

In part 2, Louis Alfieri and Amy Kole continue their discussion on the differences between Eastern and Western storytelling structures

Amy Kole is a freelance Show Writer and Immersive Storyteller who has spent the last 3 years as an embedded show writer at Universal Studios Japan. There she worked with an international team on the development of shows, experiences, retail, and special events. She possesses a Masters Degree in dramatic writing and is working on several films and scripts currently. Amy is also an avid horror fan. She recently had her collaborative work with Emma Oliver “The Corridor” published in the Horror Anthology.

Top image: Mosaic scene from Homer’s Odyssey, Ulysses meeting with sirens, from The Bardo Museum, Tunis.