by Louis Alfieri of Raven Sun Creative and Amy Kole

In our first article in this series, we covered how stories are broken down in Eastern and Western cultures from a structural perspective. We also identified significant differences in Eastern versus Western culture––such as individualism and collectivism.

In this next article, we are going to take it a step further. Here, we discuss how these storytelling conventions are applied to location-based entertainment, and how these diverging techniques inform and transform the guest role from culture to culture.

Most westerners are not fully aware of the commonalities and significant differences between Asian cultures. The designs you manifest in Japan, China, and Korea are very different, reflecting the uniqueness of each culture and population. They are not one and the same. Whether that is from a story perspective, a facility perspective, or a guest behaviour perspective.

As we mentioned previously, the culture, social norms, and behavioural dynamics of each society are manifested in the way we understand, interact, and design in a given locality. Our dialogue (creative, operational, business model, etc) is educated and influenced in every possible way by these unique dynamics and insights.

How does storytelling exhibit itself amongst Eastern and Western location-based entertainment experiences?

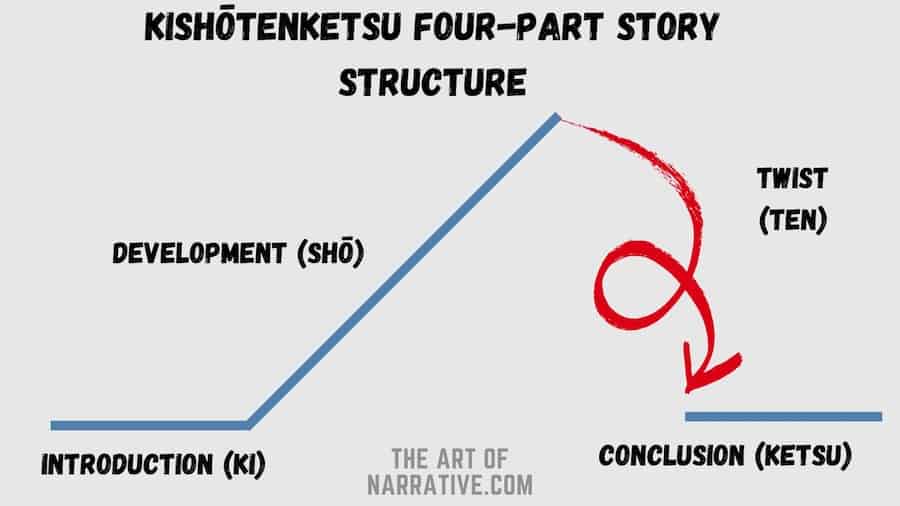

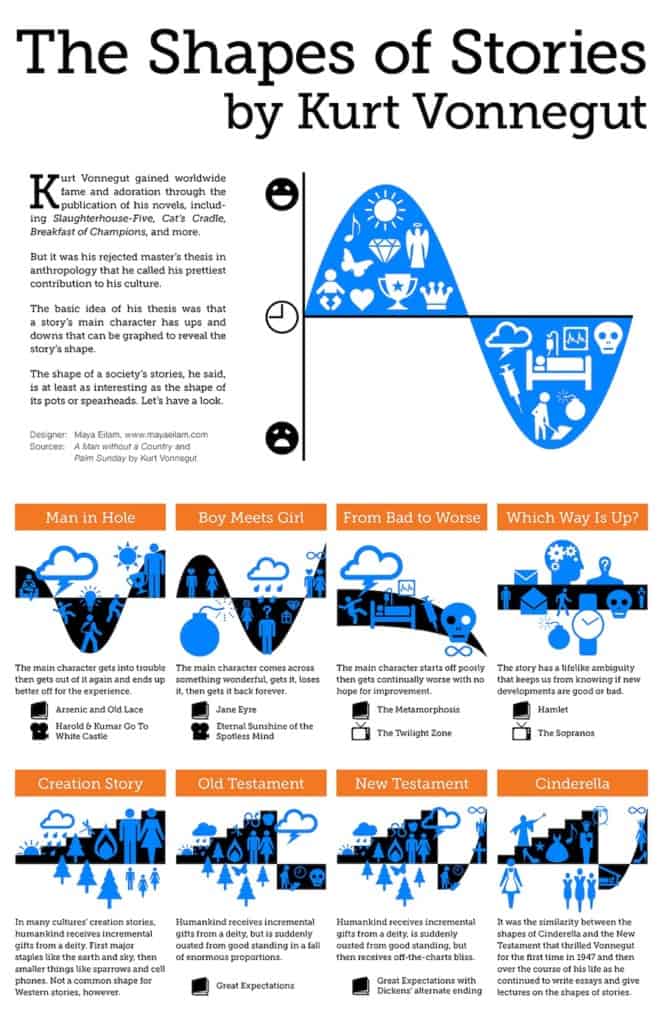

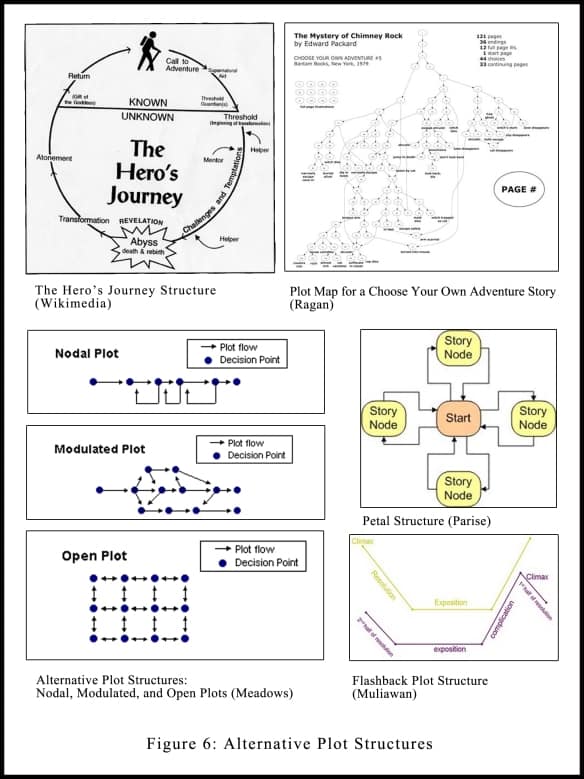

AK: As a refresher from part one of our discussion, Western stories typically follow a three or a five-act structure (The Hero’s Journey). In contrast, storytelling in Japanese culture follows four-act structures (kishōtenketsu). This four-act structure isn’t exclusive to Japan: it also appears in Chinese, known as qǐ chéng zhuǎn hé, and gi seung jeon gyeol in Korea.

Kishōtenketsu frequently occurs throughout East Asian Media and appears in jokes, mangas, poetry, and other narratives. While there are many similarities between the two structures, they present many differences as well. One of these is that the three to five-act structure needs conflict, and the four-act structure can exist without conflict.

However, the truth of the matter is, so much affects the creative process, design, and guest role because of the two cultures, and to cover everything would be more than our already-growing repertoire on the subject (not that we’d mind talking about it). Yes, the traditional storytelling structures determine a lot when it comes to LBE. But it’s far from the only determining factor. Demographic (domestic and international), social behaviour, character archetypes, technology, etc.

Cultures influence each other’s storytelling

AK: Then, of course, there’s the idea that our two cultures are becoming more and more ingrained in one another as various forms of international media and experiences find their way to other countries and fresh viewers. Take the four-act structure, for example, which originated in Asia, but is impacting how we view stories in the West.

Tom Abernathy, the lead narrative designer of Riot Games, has said that the four-act story structure is simply better suited for certain long-form immersive experiences. For instance, as in role-playing games where there are lots of characters, but a more spaced out narrative. It makes it an ideal vehicle for world-building and co-creation without inhibiting the experience with strict narrative guidelines.

He essentially claims that there’s a benefit to using a four-act structure in an experience that’s less serialized and more supporting character-driven. This is relevant to the discussion. It’s one of many examples of how the mixing of our two cultures (and ultimately, storytelling conventions) highlights the fact that we still have much to learn.

We’re so used to the idea of our own conventions. But there’s so much insight to learning, adapting, and applying these divergent narrative approaches to Western and Eastern experiences.

Immersive experinces

LA: All great points Amy. I would add to that that in the experiential medium there is an expansion on that idea. People have, up until now been accustomed to being semi-passive participants in these experiences, driven by a linear narrative.

By this I mean, you enter an attraction as a guest in the story world via the call to adventure through a portal (theatrical experience, exhibit, theme park, or other immersive experience), then following through a series of story sets ups and framing mechanisms such as the meeting of the mentor, understanding who the allies and enemies are (acts, scenes, or pre-shows).

This all results in crossing the threshold into becoming fully immersed in the experience (suspension of disbelief). Whether that be by boarding a ride vehicle, actor interface, cinematic experience, or other, depending on the application.

Taking a lead role

LA: For example, Universal Studios theme parks rely almost exclusively on a story structure and mechanism whereby something bad happens and you are drafted into service in one form or another (cadet, adventurer, etc). In Cirque du Soleil a character may inherit an object or idea to pursue/explore. In Roland Emmerichs’ films, there is the beginning of the global disaster cycle, etc.

Once immersed, there is often a repeat or reinforcement of the previous information to ensure the audience has the basics. (As an aside, often other story tropes apply here such as the Macguffin (the object we are chasing / in need of, etc. and all too often Deus Ex Machina (something inexplicable in happenstance occurs to ensure the ending we want happens).

From this moment on we are in the special world quickly approaching the Ordeal, Death, and the Rebirth which is often where the guest/audience transformation takes place, which drafts us into the service of the story.

Often at this juncture, we, the guest/audience members, take the heroic role and an ensuing climactic event takes place which we are at the centre of.

Changing the course of events

LA: Typically we do something that changes the course of events resulting in success, such as seizing the sword, figuratively outsmarting the villain or outright plunging the sword into the villain to save the world (Transformers, Harry Potter, Star Wars, Avengers, Lord of the Rings, Ocean’s Eleven, Zhang Yimou’s Hero, etc) or a major twist takes places that allows us to win (Now You See Me, M Night Shyamalan films, etc).

This is followed by an often rushed return to a cheering crowd, and an exit at a representation (possibly altered) location triumphant return to where we started (Poseidon’s Fury, Expedition Everest, Ka, Fuerza Bruta, Secret Cinema) (or close to that location, as it is often expected that you must to explain the relationship of the physical entrance and exit of an adventure being in the same location).

And the reason for that in LBE, in particular, is a practical one. You must reconnect family members or physical items with your guest after the adventure has culminated.

Breaking down the Hero’s Journey

AK: While I was at Universal Studios Japan, the writing team broke down the Hero’s Journey. Then it looked at each of the steps that accompany the structure individually. Thanks to Klaus Sommer Paulsen’s new book, Integrated Storytelling by Design: Concepts, Principles and Methods for New Narrative Dimensions, there’s a better word for these separate aspects of Westernized structure: microstories.

We looked at each microstory to decide which were absolutely necessary when designing an attraction. When you create a movie, or a book, or even a television show, there is a guarantee of at least thirty to forty-five minutes of content. An immersive experience can be shorter. Therefore, there’s much less real estate, timewise, when designing something that needs to have a beginning, middle, and end. Granted, we looked at this purely from a linear perspective.

Western cultural storytelling conventions in Japanese attractions

LA: By way of comparison, Japan (and China more recently) has also, in Western theme parks such as Universal Studios Japan, Tokyo Disneyland, Shanghai Disneyland, and soon to be Universal Studios Beijing, openly accepted the Western cultural storytelling conventions in the Western-lifted attractions.

We can also see this in the cultural sector, in the layout and design of art installations or travelling exhibitions. For example, there is a move within the cultural space to move away from chronological or classificational exposition to culturally parallel exposition (placing objects from varying classifications together in the collective state of the period of creation, i.e. WW2 / Belle Epoch, etc).

These examples may be seen through the lens that they are an acceptable form of exposure and entertainment from the Western culture. As such, I would say there is a more open reception to this conversation in Asia, where we hold these types of conversations.

Conversely many westerners are really just at the beginning of learning what the Chinese, Japanese, or Korean storytelling medium is. Mind you, we have not even mentioned Indian storytelling yet which has highly influenced East Asian storytelling! It’s in an evolving state of process in how the storytelling medium is being translated to experiential content and artistic experiences.

We are all a part of discovering and evolving what that looks like and how guests, audiences, and future creators and generations will digest it.

LBE in China moves towards following their own narratives

AK: Historically, film has a huge impact on immersive experiences and other cultural phenomena, and the film industry in China has been growing and surpassing the US in box office revenues, as well as studio sizes. Additionally, many of these films are about China’s history and stories.

You’ve mentioned before, based on your experiences designing in China, how LBE in China is moving toward following their own narratives over Western conventions and stories. Theme parks like Evergrande and Hengdian World Studios are opting to keep the technological advances from the West while developing storytelling for these experiences more closely linked to Chinese culture, identity and folklore.

Chinese storytelling and Red Culture

LA: Wow, there is so much to unpack from that statement, Amy. My mind goes to so many constellations of thought. This could easily translate into a discussion regarding the interpretation of cultural content as IP (in China now known as Red Culture), IP as a vertically integrated commercial medium, market transitions, socio-economics, and even global application of soft power through the exporting of entertainment and cultural content.

The latter is an example where China is applying concepts that the US has executed previously (intentionally or by happenstance), even going so far as to coin similar terms such as the China Dream, etc.

It is of fundamental importance to understand the architecture and intersection of culture and storytelling to make the greatest impact of emotion, human connection, and use of technologies to articulate a vision. How can we use these narrative structures and tools to touch and communicate with each audience distinctly? And how can we work to create a shared communal experience when these contrasting cultural filters and understandings overlap?

How to approach a new project

LA: When a project begins, I like to look at the creation of experiences from at least four viewpoints. These are influenced by the kind of project and application at hand.

1) Regardless of creation in the east or west, I ask what is the emotional outcome or memory we would like the audience to have? Is it joy, love, or a call to action that will result in a behavioural change? Is it awe, thrill, education, inspiration, retrospection, an emotional connection to something?

In each use case, I want to reverse engineer how to tell that story, build that bond with our audience, and the emotional journey we will go on together.

2) Should I use a universal archetype to tell this story? How does that archetype translate to a universal global audience? How does this work in the east and west? Where will it be appropriate to localize this story, and how can we build bridges between cultural understanding? How will this story and emotional journey work when both groups are sharing the same experience?

3) What technologies can I layer together in a seamless, invisible way to support our thesis? I use the analogy of a technology lasagna or an orchestra. Each element is, in itself, important. Yet when the parts are together, the sum represents something much greater than its parts. Where are the intersection points for different communities and demographics? How can I use this technology to bring everyone together?

4) Am I intent on using the technology to articulate a singular creative vision? Or am I creating a platform for the guests’ co-creation? Is this an expression of my creative vision (an art piece), a manifestation of an existing story (brand, IP, etc) or a new form of narrative being co-created in real-time?

The democratisation of the creative process

LA: The democratization of the creative process is something I’m passionate about. It is also scary and dangerous. It means you must let go of your intended vision to allow for unexpected outcomes. Especially when you are mixing cultural experiences.

AK: Developing LBE is very much like planting seeds knowing that the experience is going to transform over time. Also, you can’t guarantee sole attention in the same way that you anticipate for a movie or a book. With cameras to guide the perspective, you’re making an unspoken statement with guests that says, “Okay. All the characters and pieces of the story are here, but you need to put it in order.”

What is the guest role? What considerations need to be given when considering the guest role from an Eastern vs. Western standpoint?

AK: The guest role is not something designers consider lightly when developing a new experience. It’s given the same consideration any character receives during the development stages of a narrative. It’s one of the most important parts of any location-based entertainment. And the role of the guest fluctuates throughout different parts of the world.

For the purposes of our discussion, we are going to focus on the guest role in the West and East, based not just on the predominant narrative structures of their societies but also on cultural expectations.

The guest role is different for all types of experiences, and designers find different ways to indicate the crossing of a threshold. Sleep No More, for example, provides guests with actual masks that work to obstruct identities and place everyone in an even and quasi-anonymous playing field.

There is not always a need for costumes or props, however. This is why the guest-facing signage and script is so important. It is one of the most indicative aspects of the story that provides context and backstories.

A culture’s storytelling conventions dictate the guest role

AK: Anytime a guest enters any sort of immersive experience, be it a theme park, museum, virtual reality, or even a video game, their role transforms from passive bystander to an active character or an extension of the story world. The line between the story world and the “ordinary world” has been crossed. The culture’s storytelling conventions can dictate the character that the guest inhabits. Take, for example, the ideology we’ve already hit upon – individualism vs. collectivism.

Western society is built on the concept of individualism. And Western LBE indulges the mindset that the only person who can save the day is you.

Western society is built on the concept of individualism. And Western LBE indulges the mindset that the only person who can save the day is you. When you play a video game, the protagonist is often a “lone wolf”. They already have the means and know-how to save the day. When you visit a theme park, attractions also often feature a guest role evolving around a guest either: A) taking on the role of a hero from an existing franchise, or B) joining their favourite, or becoming the role of the hero that must save the day.

Individualism vs. collectivism

AK: Contrastingly, when designing and storytelling in a culture that surrounds collectivism, such as Japan, the guest role focuses less on the individual, and more on the collective group in the audience or on an attraction. The guest role becomes “ a heroic team, family, community, region, or country”.

This is a reflection on Eastern philosophies regarding collectivism, communal peace, and the concept of family honour, otherwise referred to as “face”. Even Eastern video games feature more communal themes than the West, finding the hero attempting to defend a community out of honour, or mastering skills through practice.

The eastern storytelling form is a result of seeing challenges, community, and world from a group perspective; the culture of a connected mindset that transcends the individual. These cultures place a very powerful emphasis on cultural consensus and group outcomes.

Of course, both of these are considered admirable traits in their individual culture. If the guest role in the United States places an emphasis on looking within to conquer conflict, then the guest role in Japan coaxes you to look outward and toward help nearby.

Storytelling, culture and Sailor Moon

AK: A more specific example of this would be the USJ attraction, Sailor Moon: The Miracle 4-D ~Moon Palace Edition~. As the show writer for this project, from the get-go, we knew we wanted a moment that would allow guests to feel that they’ve helped Sailor Moon defeat the villain, but had to go about it in a way that would create permission for interaction amongst an audience in a culture that typically strays away from moments of purposeful, group disruption.

In America, a different type of consideration would be far different. Westerners are generally more willing to interact in immersive experiences, even if it means sticking out.

Going against the grain

LA: In terms of behavioural observations, it goes both ways when we are talking about doing things that some may see as out of the norm of daily life, regardless of locality.

There is a saying in Japan along the lines of “the nail that stands up must be hammered down”. This reflects the cultural pressures against standing out, going against the grain, or disrupting the flow of the community. As such it is a primary responsibility, as a designer in the experiential medium, to create zones of permission for these acts of freedom and expression without judgement to take place.

Depending on our location in the world, we may have to offer cues to the audience about what is allowed within the confines of this experience

Depending on our location in the world, we may have to offer cues to the audience about what is allowed within the confines of this experience, that is a world away from what is expected of them in daily life.

I recently had an excellent conversation with Heather White, COO of Burning Man, regarding the same kind of permissions being created at their installation events, where they help establish zones of permission, where creative barriers are broken down during the artistic rituals shared in the western Burner community. In this way, we are seeing both divergent and convergent behaviour in the role of the guest across different cultural expectations and social etiquette.

Asking why

AK: But what about China? China follows the four-act structure like Japan. Does that mean the guest role is similar to Japanese guest roles?

LA: The journey of the hero, in the western sense, is not typically as well embraced as a guest trope in China. Don’t get me wrong, Chinese audiences absolutely celebrate the journey of the hero. However, its implementation in the experiential medium may be applied differently.

There have been many instances where guests and creative collaborators have asked, “Why?”

For instance, “Why do I have to win at the end of the ride, why does it have to end with a climactic battle? Why do I have to go through these steps in the exhibit? And why must we tell the theatrical experience in this act structure?”

This same series of questions may also be seen in the domestic developed experiential entertainment in Japan and Korea.

Returning to zones of permission, we applied that differently in China 10-12 years ago to how we do that now.

10-12 years ago, our role was to help craft the permission narrative about what should the guest do in this experiential environment. Now, we are at a point in the evolution of the audience where our permission structure is much more complex and robust with an audience who is open to challenge, very vocal, more embracing of social conflict, and possesses rapidly escalating expectations.

Opportunities for reflection on storytelling and culture

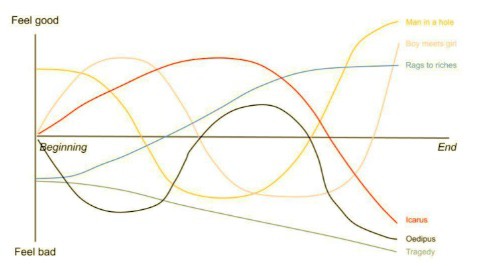

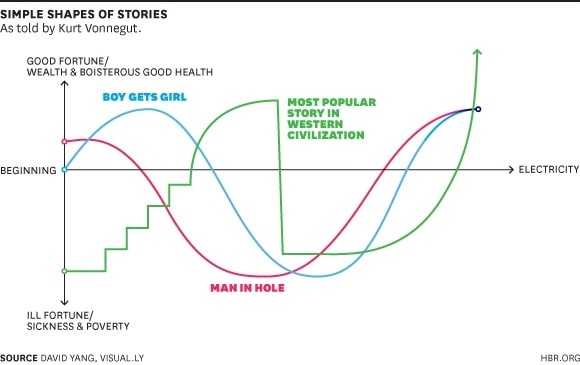

AK: That’s going back to the notion of how the four-act structure doesn’t always need to have conflict. And the idea that you mentioned in article one, how not all Eastern narratives have to end happily ever after.

Perhaps instead of pushing against it, there’s something we can learn when applying a traditional four-act structure to a Western LBE experience

Perhaps instead of pushing against it, there’s something we can learn when applying a traditional four-act structure to a Western LBE experience. Why do storytelling narratives have to live in their own cultures? Shouldn’t we always strive for the highest quality, even if it doesn’t look familiar?

LA: These questions are 100% valid and right. Why do we do things we do? And why do we have to follow the rules our culture teaches us? The questions and self-reflection represent a humbling opportunity to listen, learn, and absorb other cultures’ methods. We can then apply these globally as designers. It does not have to be the American, Disney, or Grimm way of storytelling.

How can technology influence storytelling and lead the way for multicultural experiences?

AK: Something that designers have access to nowadays that will better help us understand and design for other cultures is technology. In my personal opinion, the medium of storytelling that can help us answer this question is video games.

I find that there’s a ton of crossover between video games and numerous immersive experiences, especially theme parks. Both must exist within a rich story world in order to allow players (or guests) the freedom to branch off and create their own narratives and become co-creators.

Even an experience like teamLab, which isn’t a linear experience, gives visitors the opportunity to create their own creatures. It then brings the creatures to life to interact with everyone else’s creations.

Of course, there’s also other promising aspects of technology that will further help instil a universal experience across multiple cultures and languages simultaneously.

New technological developments

LA: We are at the point in technological development that will allow us to take this aforementioned structure and throw it out on its ear.

We are at that moment in time where, whether that be by a passive solution or highly personalizable interactive solution, we are now at the edge of being able to create non-linear multi-branching narratives that will allow participants the ability to play different roles in experiences resulting in numerous and vastly different outcomes. For example, what if I want to be the villain and not the hero?

This remarkable juncture is going to take us from story-telling to story-living in the metaverse.

Story-living

AK: Story-living. That’s so exciting. It’s an idea that returns us to our roots of playing and creating worlds with blocks or Lego, designing set pieces, naming characters. Adults often abandon the idea of play. I love that this type of medium gives you permission to step back into that mindset and create your own ministar in a vaster narrative. Not just on your own, but among groups and with friends.

That does make me wonder how the metaverse will allow so many cultures to interact at once. Especially when immersion means different things in Eastern and Western culture. It seems as though the closest medium we have to test out the metaverse experience would be something like VR.

VR and cultural storytelling

AK: Another aspect of video games we can learn from as experiential designers is the Bartle Taxonomy of Player Types. This theory places video game players into different classes of gamers:

- Achievers – Gamers who perceive success through achievements, level advancements, coin-gaining, etc.

- Explorers – Gamers who prefer to explore the gameworld and deep-dive into the environment at their own pace

- Socializers – Gamers who enjoy interacting with characters, or socializing through the gameworld or engine

- Killers – As violent as this classification sounds, it’s merely referring to gamers who enjoy the competitive nature of gaming

LBE has its own classification for its experiences. Waders skim the surface of the experience, swimmers immerse themselves fully, and divers seek to experience it all.

There’s a lot of connective tissue between this theory and Bartle’s Taxonomy of Player Types. But what I like about the Bartle Taxonomy of Players is that it’s less rigid than the waders, swimmers, and divers theory. It exists more on a spectrum geared toward play and gamification rather than just environmental and scripted narratives.

Using VR as a template

AK: When it comes to Eastern and Western cultures, a medium (such as VR) could provide an excellent template for integrating themes, archetypes, languages, and societal buffers in real-time and throughout a range of role-playing, skill-testing, and socially-geared experiences, all joined simultaneously in real-time.

And these gaming archetypes could help indicate more than just gaming preferences. There’s an opportunity to learn more about the cultural diversity of gameplays from other sides of the world. This is an interaction that could only be duplicated in real life.

VR as a storytelling medium

LA: In my opinion, VR is a global storytelling medium that has, as of yet, not reached a transcendent experience. The Void is probably the closest thing to a working storytelling medium. VR, in my perspective, is really not a passive storytelling medium.

VR, when it reaches a transcendent state, is more of a story living medium. One where you are going in a non-linear fashion through a game engine

VR, when it reaches a transcendent state, is more of a story living medium. One where you are going in a non-linear fashion through a game engine. You are able to influence all of your choices in a non-linear narrative based on your behaviour and the choices you make. There hasn’t been a medium that allows us to enter a world by ourselves.

VR allows us on a constantly evolving choice-based scenario (based on the intelligence of AI and the game engine). People in VR at the moment, and this is an intersection point of Eastern and Western cultural storytelling in real-time, can have this dialogue around the world right now about how these different modes of storytelling respond either individually or collectively in that virtual world.

Waders, Swimmers and Divers

LA: As for Waders, Swimmers, and Divers, it is possible to interpret that as widely and differently as each creative can interpret a story.

It is my opinion that your diver is an avid explorer. Someone likely to experiment with several approaches, and several of the archetypes. Their intention will be to unlock many of the games secrets. They will continue to play through the story from several angles until they settle on something that emotionally resonates with them.

Your wader would be someone who plays the game at a cursory level. Then, your swimmer would be an adept game player who could enjoy some of the nuances of the game but is not dedicated to learning every character’s signature move, or to locate every easter egg located in the experience, game, or film (for example hidden Mickeys / or the Cucco Revenge Attack (Legend of Zelda), or the references in Toy Story to the Shining).

A push for more culturally relevant experiences

AK: Going back to what you said earlier about how in China, there’s a push for more culturally relevant experiences. And technology really allows, more than ever, for the past and present to unite. For example, at the Palace Museum in Beijing, visitors can use VR to experience the Forbidden City.

Technology really allows, more than ever, for the past and present to unite

There’s a great quote in an article by Wang Yuegong, the deputy curator of the museum. This really sums up the point of the cross-pollination of culture, technology, and immersive storytelling experiences.

“As the Palace Museum has been committed to the research of advanced technologies and the display of its cultural heritage, it is our mission to build a museum that caters to the needs of the era.”

During your video interview with CEC, one key point was that technology isn’t utilizing VR to its fullest potential in more ways than just entertainment. It’s a way of filling in the gaps missing in other cultures to create a more unified experience. Especially when it comes to things such as training or education.

Historically, this is the type of technology geared toward real-life application along with experiences designed for IPs or themed excursions.

Moving on from culture and storytelling

AK: However, until then, people are still designing experiences every day. It’s always exciting to speculate the future of immersive design. However, the here and now in the world of LBE is also exciting. Well, to us, at least. We’ve talked about how the outside world and culture influence storytelling and the story world. But how does it influence physical design?

The influence of the physical and societal elements of Eastern and Western offer incredible insights into the development of LBE. In our next article, we’ll take a step away from narrative. Instead, we will explore how societal behaviour, expectation, and desire inform so much of the production and creative process. We will also give some insight as to what it is to be an ex-pat living––and working––in an Eastern culture.

Amy Kole is a freelance Show Writer and Immersive Storyteller. She has spent the last 3 years as an embedded show writer at Universal Studios Japan. There she worked with an international team on the development of shows, experiences, retail, and special events. Amy possesses a Masters Degree in dramatic writing and is working on several films and scripts currently. Amy is also an avid horror fan. She recently had her collaborative work with Emma Oliver “The Corridor” published in the Horror Anthology.

Top image: Shen Zhou/WikiCommons