by Louis Alfieri of Raven Sun Creative and Amy Kole

The experience of designing in another culture opens many opportunities, as well as considerations that differ from culture to culture. In the first article, Louis Alfieri and Amy Kole covered the differences in storytelling techniques between the East and West. Following this, article two took a deeper look into what the design process manifests into when creating experiences for different audiences from a narrative and guest role.

In the third piece of this East meets West series, Louis and Amy now talk about how society helps to inform physical design with consideration of the guests embarking on each experience. This goes beyond the story: it involves sizing, location, and family dynamics within individual societies.

What type of physical and societal conventions do designers need to be aware of when designing an immersive experience for an Eastern audience? How does this differ when designing for a Western audience?

AK: When Americans hear the phrase, “the bigger, the better,” chances are they think of Texas. However, I now associate that expression with location-based entertainment developed overseas.

I think it would surprise people to learn (especially in China) that while story and the guest role play significant roles when designing the world of the experience, so much of the outside world dictates a lot of design needs.

Guests walk into a story world and assume a role. However, the outside world where they’re coming from also needs consideration. Everything from the standard size of groupings for travelling companions to the common courtesies of the society determines and indicates so much about the audience.

Louis, do you have much insight as to how this looks in China amongst the location-based entertainment landscape?

Organising for different groups and cultures

LA: In the United States, we tend to look at the story, spatial, and operational design of a mixed-use destination, museum, theme park, or theatrical experience centred around two or four people, who are travelling to the site individually by car (in Europe this would more often be via mass transportation).

This nuclear family group usually consists of two parents and two children, or two grandparents, one adult and one grandchild, or a young adult couple and set of parents. Adjacent to this primary group structure, we anticipate the story, spatial, and operational organization to support group tours, corporate events, schools events, etc.

In Japan, there are numerical similarities. However, there is a significant cultural difference between Japan and the US in terms of personal space that will influence the density of story, content, and humans.

In China, the scaling of space and visitor density is very different. You’re always organizing for groups of three, seven or upwards of 20-60 depending on tour size. The nuclear family unit in China consists of three – two parents and one child. Seven is a standard constant, which reflects two sets of grandparents, two parents, and one child.

New experiences

AK: Size isn’t the only thing to consider, either. As we touched upon previously, the entertainment sector in China is booming. It is only becoming more established in the past twenty-something years. This means that you don’t just have to accommodate for size. You’re also accomodating for a group of visitors who haven’t experienced something quite like the phenomena that is a museum.

We must ask ourselves, as designers, what type of interaction can we hope for given the wonderfully diverse etiquette from culture to culture?

Thankfully, our definition of “art” has shifted and transformed into something that might be unrecognizable when put up against a traditional museum. This opens the doorway of possibilities for anyone with an imagination, regardless of their exposure to art, or museum etiquette. However, as our technology expands, so do these locations that help break down the barriers of who can enjoy art.

More accessible art

AK: teamLab is a group we discuss a lot. Something else that’s so incredible about teamLab, especially from the perspective of the vastness of the audiences in China, is that the exhibit is meant for a large crowd. Its non-traditional layout makes it a fantastic entry point for newer museum-goers. The spectators become part of the spectacle.

One interesting article quotes Bonnie Zhang:

“Traditional art exhibitions require the audience to understand the painter, art theory, and background knowledge. But an exhibition like this can be seen and understood by everyone.”

This is poignant for a culture such as China which is new to these types of experiences. The point of entry for the experience may seem less intimidating, or at least more accessible for new art experiencers.

This wasn’t the only consideration when designing Shanghai’s locale. They also indeed adapted the Shanghai exhibit differently from the Tokyo location in anticipation of the larger crowds. Forest of Lamps, my personal favourite exhibit from teamLab, is in both the Japanese and Shanghai locations. The Shanghai site recreates the experience in an environment one point five times larger than in Japan.

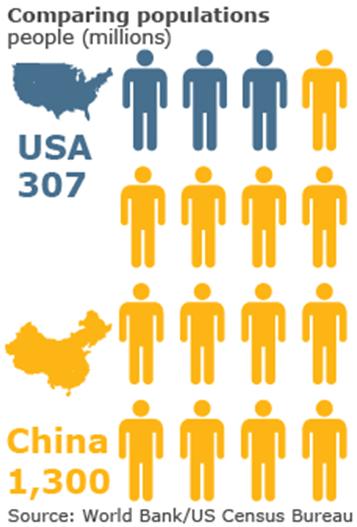

Differences in population

LA: Beyond China, this sense of co-creation, audience participation, and real-time user-generated content and experience is new everywhere. As I have spoken and written on recently, we are moving from 5000 years of conventional storytelling to a new future of storytelling. Now, there is an almost unlimited amount of input and variation capable at every level of engagement.

Returning to your point about the differences between western and eastern versions of teamLab, this is a result of very different vacation and population density patterns in the societies. In Asia, and in China and Japan, in particular, there are periods such as Golden Week when the majority of the population is on the move simultaneously.

Every space, every portal, every pathway, in a museum or park tends to be massive in an effort to support these cultural recreation/mass population movement peaks. The numbers are staggering. Many people have a difficult time imagining what a crowd of this capacity looks like in person.

By way of comparison, we need to understand the scale of differences in population. There are approx 1.7 billion people in China. This is compared with 330 million in the US, 175 million in Japan, and 45 million in Korea.

Japanese population & culture

LA: For an example of population density, people are unaware that Japan has 175 million people (roughly ⅔ of all of the people in the United States) living in a gross landmass the size of California. Plus, only 25% of that landmass is inhabitable space as a result of steep mountains, seismic activity, and the makeup of the islands. It’s insanely dense.

Living spaces are small. It’s predicated on a sense of how they need to organize themselves visually in society and in space. When Japanese guests go to a theme park, they’re not all pushing to get in the door: they will self-queue. It’s a social function. It’s not reflective of the theme park, but the theme park takes its cue and design from the notion of how that culture behaves and functions. And in his case, that culture and function is a reflection of the environment in which they live.

Continuing our understanding of scale, The Shanghai/Yellow River Delta and Beijing/Tianjin metropolitan regions are both likely to exceed 70 million people by 2025. Currently, no other megalopolis is envisioned in other countries. India could one day follow suit in Mumbai or Delhi. By 2025 More than 100 cities in China will exceed 10 million people.

In Japan, by 2025 only greater Tokyo (36 million) and greater Osaka (18 million) are of this scale. In the US only greater New York (18 million) and greater Los Angeles (12 million) can rival this.

Designing for crowds

LA: Returning to the previous comment, in China for example we are talking about a mass movement of the population during the Spring Festival of approximately 950 million people simultaneously. This is roughly equal to almost 3x of the entire US population moving at the same time.

These cultural and volumetric scale differences influence how we can design and deliver a story and experience to guests in varying formats, markets, and categories.

AK: That leads to another interesting point: how you design for a massive crowd and anticipate how the group will automatically organize themselves. For example, if you approach a queue line in America for any type of experience, guests understand that they need to line up based on parameters that are provided (dividers, signs, floor indicators, etc.)

I don’t think Americans typically want to line up, but societal expectations have taught us that we need to organize. However, if you take away those parameters, you’ll typically see a line lose its form and turn into a crowd.

Japanese people, as you pointed out, will self-queue even without prompting. The lack of queue lines for specific experiences in Japanese theme parks confused me. Many of the character meet and greet experiences weren’t behind an official queue. But I understood why fairly quickly: they aren’t necessary.

However, in China, the flow of physical organization tends to fall away due to the size of crowds.

Competing for resources

LA: Although you might find that parks appear on the surface to be more spacious in China, the queue lines are designed to narrow in, in an attempt to help the operators and crowds maintain control by means of limiting the number of visitors able to inhabit a space at a single time.

This is also a cultural reflection on personal and business competition. As we noted the scale is so vastly different. This social reality reflects that many people are vying for the same resources and time at once. Thus it is considered social conditioning and reasonable to compete for access to those resources.

This type of social conditioning is not exclusive to a theme park. We can see the same type of resource competition for doctors in a hospital, taxi access, schools, etc. To be an effective experience designer, you need to be a willing student in observing social etiquette, anthropology, psychology, sociology, and even economics.

Social media and culture

AK: Extending that series of studies, today another major consideration is social media and its relationship with these types of experiences. The importance of social media in the lives of young adults (who are also a huge demographic for these experiences all over the world) helps determine if they’re going to travel or pay for the experience at all.

There’s something about “belonging” and taking part in trends that become a subset of the larger immersive experiences. In other words, an attraction or experience within an attraction or experience. Yes, you are paying to see teamLab or ride the newest Attack on Titan roller coaster. Yet, oftentimes, the real experience that guests are seeking isn’t the attraction: it’s the photo.

In cultures such as Japan, China, and even America, getting the photo is merely one of the attractions or experiences. This informs the design, as well: what do you build in anticipation of this sort of interactivity, and how can you make it relevant to the story and guest role?

Designers leave so many story scraps on the table when they don’t take the opportunity to link the core narrative with an image that’s about to be unveiled over and over through social media channels. And this isn’t a Japanese, or even an Asian phenomenon. Social media has become a language without dialogue or dialect that we can share with other experiencers.

How have your own experiences as a Westerner in Asia influenced how you approach story or design? How is language and culture used in different ways to guide the guests through experiences differently?

AK: The four-act story structure is an obvious answer in contrast to my sensible, Western, three-act ways. Like so many Americans (or rather, writers, I doubt the average American pontificates story structure, though I could be surprised), I hadn’t given other narrative outlines much thought. Honestly, I’d barely considered even Western storytelling conventions before I started to pursue writing before I went to grad school.

I wouldn’t say that it’s a faux pas per se to approach attractions in the East from a three-act structure. But it’s clearly important to consider what the experience needs from a narrative perspective. Like Tom Abernathy pointed out (in article 2), some experiences may possibly benefit from a four-act structure, even in the West.

I don’t say this from experience, but it’s an interesting thought.

Something else I was struck by was how sounds are used as different modes of communication without dialogue. Many people don’t realize that so much Asian conveyance is non-verbal. Onomatopoeia plays a huge role in reading the other person, whether in a casual conversation or during a business meeting.

I realize that I start to panic when I relate a story and receive no reaction from the person sitting across from me. Then I remember that it isn’t a standard part of communication in the West.

Multi-layered social communication

LA: This is part of the discussion too: how to interpret what sounds mean in a complex multi-layered social communication structure and hierarchy where words are not the only form of communication, and how to understand the statement being shared.

Furthermore, in these multi-layered cultures, when we’re creating or we’re articulating an experience together, sound and body language represent whole other toolsets and communication sets to tell story, emotion, and nuance that is often missing to the Westerner.

There are not a lot of sounds that Americans will make in a meeting that reveal details of their perspective or mindset. We are attuned to a deep breath in surprise, the tone of frustration, or laughter in collective appreciation or at an idea that may not be as well-received as we would like.

In Japan, China, Korea, and even the Middle East sound and body language have profound importance

In Japan, China, Korea, and even the Middle East sound and body language have profound importance. There are sounds associated with air moving through teeth, sounds and movements for acknowledgements, sounds and body postures that signal problematic ideas, even angles of bowing has many meanings relative to the respect and significance you are sharing in the room together.

These are messages that are being translated and communicated to articulate what the person or group’s true state and intentions are in a particular setting. All of these messages are important factors in truly listening and the experience of designing and working within another culture.

Reading body language and more

LA: It can be much harder to identify and read body language in a group setting. It is critical to embed oneself in the culture to absorb, reflect, and articulate those learnings in the design and development process, and further to listen across all of these information points and how guests received the attraction.

As westerners, we lack this nuanced understanding of the physicality of expression through sound and subtle movement. Traditional Chinese and Japanese theatre offer valuable insights into the study of these forms of communication and storytelling.

As we extend this understanding further, we need to explore how this translates to the experiential medium in a narrative setting, physical environment, and now even through the phygital manifestation across digital and physical mediums For example, how do you read a crowd’s sound and physical movements to an experience? How are they digesting the material that you’re creating? How are they responding?

I remember in 2006 I went to the Summer Sonic concert with Joe Casey (EVP of Universal Studios Hollywood) when we were building Hollywood Dream at USJ. Amongst a crowd of some 25,000, we saw Iron Maiden play an amazing set. It was almost surreal, however, as the crowd was almost silent during the band’s musical numbers until queued by the band that it was ok to react. Once the band gave their approval, the audience’s cheers and energy was deafening.

AK: Yes, yes! I had to learn that a silent reaction was not always a bad one.

Symbolism and numerology in Asian cultures

LA: Another massive consideration in other cultures is the importance of symbolism and numerology. In China and Japan, numbers play a very important role in all decision making. There are companies that specialize in determining auspicious days to make decisions, open stores, reveal an idea, get married, etc.

Numbers such as 4 and 8 have very significant meanings in Asia. Westerners need to be educated in this, so as to leverage positive meaning and avoid negative meanings. Wikipedia even has a section on Chinese numerology. This helps to, at the most surface level, articulate the importance of the core set of numbers.

This same is true of the importance of direction (North, South, East, and West) and the elements (Fire, Water, Earth, Wind).

In Japan, there is even a great deal of interest and study on what your blood type is. I remember the first time someone came up and asked me what my blood type was. I was taken aback thinking it was one of the strangest things. These topics alone are a great article we can circle back to in a future discussion.

A more nuanced approach

LA: How do we as Westerners learn to read that or incorporate that kind of input into what we’re creating? We need to open ourselves, interpret that information, and absorb it. Otherwise, we’re essentially losing more than 50% of our communication skills.

How do we as Westerners learn to read that or incorporate that kind of input into what we’re creating? We need to open ourselves, interpret that information, and absorb it.

If we don’t understand half of what is being said to us in the physicality, sounds that they’re making, what the numbers mean, and sense of placement in direction, we also lose the ability to interpret that into the stories we’re creating and the experiences being exhibited for those guests. We’re only working with less than half of a toolset. But there’s all this other information in Asia that we can engage in and utilize.

We lack that nuance as Westerners. Sometimes that’s a bonus allowing the team the liberty to create outside of social constraint, as you are both participating in an experience and development process, where you are forgiven for breaking that barrier because you’re not expected to know all the details of that physicality.

In other cases, it’s a detriment because you may make a major social error. Or, you left so many valuable communication tools on the table that could have elevated every moment in the experience.

Non-verbal cues

AK: I agree, there’s an entire mode of communication that transcends dialogue and it’s a huge opportunity for us to tap into it as experiential designers and global storytellers. It could potentially close at least some language gaps with international guests.

Speaking of sound, the lack of noise in certain situations is also revealing of Japanese culture. I’m not sure how it would compare to China, but any sporting or theatre event was quiet. I attended a sumo wrestling competition during my interview week. You could have heard a pin drop during the event. My companions told me that it was especially noisy that evening.

LA: What you said about opportunities to hone non-verbal skills is especially true for our line of work in location-based entertainment.

So many people think that the intention in creating an experience is to re-create a movie-going experience. We often work with environmental and visual storytelling. Often, the less text or dialogue we have to rely on, the better it is. Especially when you’re anticipating grouping guests from multiple other countries, cultures, and belief systems together simultaneously.

It would be wonderful to properly utilize onomatopoeia to further an experience in a way that’s universal. The question is: how can you take some of what we do and what’s there locally and create something new together?

Differences in communication

LA: I think our role is as ambassadors and directors. How can we introduce each other, find the beauty in those moments and cultures? And then how do we pick the right notes with each one to work together so that we can make a new piece of music that all people will enjoy, be touched by, and hopefully create cherished memories?

Circling back, in Asian culture, there is much more room for silence and contemplation in conversations and meetings. In the West, silence is often seen as discomfort, that the quiet must be filled. In the East, silence is an opportunity to gain understanding, to open the mind, and to show respect.

This silence and use of space and time is also a reflection of different business and communication cultures. Westerners, particularly Americans, are geared to move directly to make a deal happen or to move a presentation along to keep people’s attention. They share the outcome first, then a hypothesis, and then back up data to support the outcome.

In Asia, and even Germany, and some other European countries, it is the opposite. Background information should be shared first, followed by a hypothesis, and then the outcome. This notion of getting to the point is approached in very different ways culturally. The use of time and audio queues is a further illumination of this difference.

AK: There’s so much beauty and innovation in both cultures. When you’re designing an experience, you always want to ask yourself, what does it want to be? Culture is such an important indicator. Not just of what guests want to experience, but also of the role they want to inhabit along the way.

What kinds of behaviours do you need to be aware of when designing through a different cultural lens?

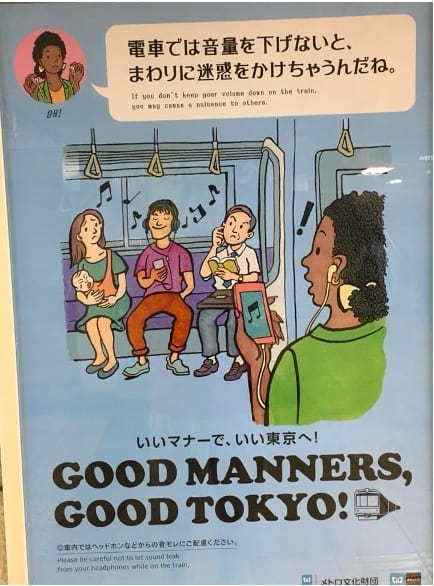

AK: Japan has so many unspoken considerations. I say “considerations” over “rules”, as certain expectations aren’t enforced because they’re the law. They’re followed because it’s a deliberate choice to consider fellow citizens. In other words, many Japanese don’t follow rules or laws out of legal obligation, but rather out of social expectation.

LA: There’s something in Japanese society about the sensibility of following order, and an unspoken understanding of their cultural social contract, that is endemic for when you create an experience there. The rules for what you’re doing at an experiential entertainment event are applied differently than you would in China.

Again we should apply this through the lens of a greater understanding of the larger cultural issues than one would normally think of in a design process.

For example, as we noted earlier, Japan has 175 million people living in the equivalent of the landmass of California. Japanese social conditioning is based on intense density, thus order and function are necessary for life to operate efficiently. As a result, when Japanese guests go to a theme park, they will self-queue.

Entertainment fans

LA: Japanese people are similar to Americans in that they like to digest experiential entertainment on a regular basis. As a fan base, they’re considerably more passionate than Americans in the same environment.

Whether attending a baseball game, theme park, or festival, Japanese visitors regularly go to events in costume; they’ll spend the entire time at an event from open to close. These visitors are emphatic about joining into the experience, being in the moment, and participating at a richer level than most westerners.

They know the story and they go in costume. They know the script, they know details about the music, performers, athletes, venue. It’s humbling, impressive, and also sometimes stressful (as sometimes this passion can extend to a desire to exhibit perfection at a particular facet of fandom or hobby).

AK: The self-sustained order in Japan is astonishing. It comes back to how Japan is a culture built around the concept of collectivism. You see it in so many facets of everyday life in Japan. From the organized lines of people waiting to get onto the train during rush hour, to guests self-lining to meet Mickey and Minnie in Tokyo Disneyland.

What observations have you been able to make in China?

A land of superlatives

LA: In China, we are talking about a land of superlatives. China is as big as the United States, yet has over 4.5 times the population. In China, the audiences typically don’t like day-long experiences or thrill rides. The Chinese audience prefers theatrical experiences. Yet in that experience, they currently exhibit a thirst for variety, a constant stream of new content happening in front of them.

Currently, nuance is less important than wow, exoticism, and speed. It’s like “how much can I see quickly.”

This is, again, reflective of their entire culture being on fast-forward as they compress hundreds of years of development into a single generation. This desire for choice and variety reflects the way the Chinese audience and consumers perceive value. In both cases, it speaks to the state of their economic and social realities.

On competition

LA: In the case of China, I see so much captured and reflected in a sense of competition amongst the population. So many people are working very hard to get ahead, get their piece of the Chinese Dream, to arrive on the world stage.

There are some cultural parallels to how the US must have felt when our grandparents emerged from World War 2. Vast manufacturing capability, a growing middle class, and discretionary income were all rising. But a huge difference to that period is the vastness of the Chinese population. This is driving hyper-competition amongst the citizenry.

You see this in how people move in tightly to get to the front of a line, event, taxi, or on and off of a plane. Or yelling and waving to get a doctor’s attention in a hospital. Everywhere hardworking people are vying for their piece of the pie amongst a huge number of competitors (other Chinese citizens) wanting access to the same assets.

Culture and food

AK: I suppose it’s pretty different from the type of value that people perceive in Japan. A restaurant or experience with a long wait was a good sign. It meant that the food must be good, or the museum must be really interesting. Especially when it comes to pop-up food and drink stands. It’s going to go away soon, so you need to get a crepe or boba tea right now.

That’s something else we sort of miss out on in the West: cultural experiences through food.

LA: Food and experience have a lot to say about each other and how they inform each other. Food and the culture surrounding it are such an integral part of social structure, rituals, and community. Food culture is foundational to building relationships and trust in the east.

In the west, it varies greatly. In Europe, food is a way of life. People spend hours cultivating conversation, enjoying the flavours, and enjoying life. But in the US, there is virtually no food culture. It’s almost as though it’s an inconvenience to rush through most of the time.

From my perspective, these variations reflect the maturity of European and Asian perspectives on life, country, and culture throughout history, and the US’s short 200-year history as a great experiment rushing from one thing to the next as young people so often do.

Social sharing

LA: In the West, you’re trusting the chef to cultivate the flavours that are going to arrive on your plate. It’s totally the opposite in China. Here, the host is choosing twenty to thirty dishes because they’re the one identifying different textures and flavours for all of the guests. They are the arbiter of taste and experience for their audience. It’s a different sense of how to trust and create that communal experience for the guest.

All of these behaviours relate to, and influence, how experiences work. Food is such an important part of culture

Further, you always eat family-style in China, whether with a group of colleagues, friends, or family members.

In Japan, social sharing is fine but you have to flip the chopsticks over. This is so nobody’s food is in contact with where your mouth has been touching the utensil. In the West, nobody shares food at a group dinner for colleagues and friends. However, it is more accepted in the family setting.

All of these behaviours relate to, and influence, how experiences work. Food is such an important part of culture. It is a critical tool in illuminating our understanding of experience, and how to be inspired to handle it differently in each of these cultures.

Different cultures, different rules

AK: It surprises a lot of people who visit Japan just how specific the train etiquette is, and what’s acceptable or unacceptable. First off, as we’ve mentioned before, Japanese people self-queue. If the train is even a second behind, there’s a formal apology made by the conductor.

Once on board, it isn’t unusual to be so crowded during rush hours that you’re pressed into a complete stranger. It’s rude to eat or drink, but interestingly enough, a lot of people sleep during their commutes. This is in part due to the work culture and the long working hours. Passengers will consider it rude to awaken someone who is alseep on the train. Chances are that they need the sleep, and they’ve earned it.

Speaking both languages

AK: As distinctive as the experience of an ex-pat is, another designer in the industry brings an especially unique perspective. Those who speak both languages, and who bridge the translations while simultaneously switching back and forth between two tongues.

Direct translations during the design process, as you can imagine, rarely come out perfect, verbatim, and clear. There’s a unit of hardworking individuals who act as the gatekeepers between the different languages in ways that extend beyond grammatical edits. Translators and bilingual writers must find ways to bridge any cultural gaps, jokes, pop culture references, etc.

LA: In a continuation of our discussion regarding east-west, next we are going to invite participation from some wonderful people. They are bilingual creators, storytellers, and interpreters who have been instrumental in building cultural consensus, mutual understanding, and successful cross-cultural building in the entertainment, culture, and immersive art sectors.

Interpreters in Japan and China have been some of my greatest mentors and advisors. I am eternally grateful and indebted to every one of them for educating me, sharing with me, and bringing so much to life for our guests and visitors. Without them, virtually nothing would move forward.

AK: I can’t wait to hear their thoughts! As well as learn a bit more of what goes through their head when they work with designers. After all: they’re often the gatekeepers of the ideas!