In Part 3 of their conversation about interactive narrative experiences, Raven Sun Creative’s Louis Alfieri and Tim Madison explore different types of multi-branching narratives.

Understanding the multi-branching narrative tree

Louis Alfieri: As a storytelling form, interactive narrative offers destinations amazing potential for engaging more deeply and personally with their guests. It’s a subject I’d love to see more visitor institutions and professionals throughout our industry become familiar with and open to implementing.

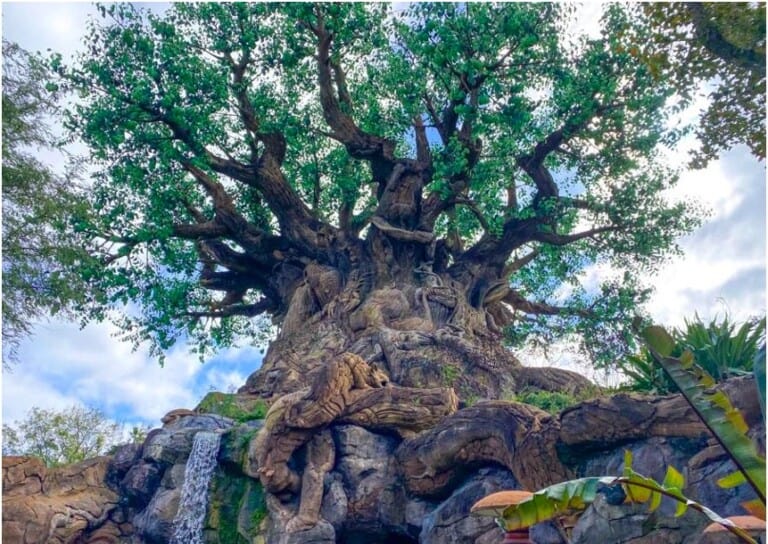

To that end, I want to talk about the kinds of structures that are the foundation of interactive narrative. In particular, multi-branching tree structures. The decision tree-style structures are the most common formats for building an interactive story.

First, let’s take a high-level look at the major types of multi-branching narrative structures. I want to stress in advance that these aren’t mutually exclusive approaches for building interactive narratives. They can all be combined and intermixed in an endless variety of ways—and often are.

We want to highlight some of the common configurations that you’ll see in branching narratives.

Tim Madison: I think it’s most useful to think of the different narrative structures as types of maps or floorplans. Not maps of the geography or spaces within a game or an experience.

In this case, we’re talking about maps that chart all the possible narrative threads a participant can follow to an endpoint. Sometimes that’s very closely related to the spaces and landscapes; sometimes spaces are designed to channel the narrative.

What we’re really charting, though, are the invisible connections between story nodes. Plot maps, in other words.

The String of Pearls map

LA: In part one of this series, we talked about the string of pearls narrative structure. Here, there is a linear main narrative along with a number of smaller branches along the way, often in the form of a side quest, optional mission, or simply areas that allow some free-roaming exploration.

These branches don’t usually significantly impact the main storyline. The participant either rejoins the larger narrative or meets some premature ending and must restart from an earlier point.

TM: This is one of the most common, if not the most common, structures we see in gaming. There’s a strong narrative through-line with branches along the way that make it feel like a less linear experience.

The Branch-and-Bottleneck map

LA: Another way to manage the complexity of diverging storylines is the branch-and-bottleneck structure. In this multi-branching narrative structure, there are decision points along the core storyline which offer the participant a choice of narrative paths; those paths while diverging on their own for a while, will eventually rejoin the larger narrative.

This format presents a certain range of choices for the participant while always reconverging on the larger narrative through-line.

From the standpoint of repeatability, it is important to keep in mind that if divergent narrative paths lead back to the same point, the experience runs the risk of making the participant’s previous choices feel pointless and throwaway. It’s as though their choices didn’t have a real impact on the larger story.

Tracking the state of play

One method for making the paths a participant has taken feel more unique and impactful is to introduce a state-tracking mechanic to the narrative that changes how the experience plays out.

State-tracking takes into account certain choices, actions, or current conditions of a participant. This means that when the participant rejoins the main narrative, the current state impacts other variable aspects of the experience.

The game or experience “remembers” what has happened. It recognizes an altered state and as a result, certain elements of a narrative branch are different based on the choices or actions of the participant.

For instance, in a game, a non-player character you encounter might react to you differently based on a previous decision you made. Or the actions you take may unlock a feature that would be otherwise inaccessible.

Different variables

Creators can deploy many variables to influence the participant’s “state” in an interactive narrative, including:

- Score

- Character’s reputation

- Character’s skill level

- Special items acquired

- Time elapsed in the game/experience

- Objectives achieved

TM: Tracking and accounting for variables does make a game or experience feel more personal; as if it’s growing organically out of what’s come before. It also means you can have variation within a single narrative branch without needing to create an entirely divergent branch. This offers nuances of difference throughout the experience.

Of course, every scripted variation in an experience means there will be more content to create. With every variable you add to an interactive narrative, you are increasing the complexity of the design.

It pays to think very strategically about what variables you want to impact the state of an interactive narrative. To a certain extent, it’s a less-is-more situation. Variability, in and of itself, does not always translate into substantial value for the participant. Designers and writers need to ask what variable aspects really feel meaningful for a participant.

The map of many endings

LA: We’ve talked previously about the ever-branching model. This is where the participant keeps coming to decision points and must choose between two or more options. Each option leads them down a unique path toward one of many different final outcomes.

This sounds very interesting and exciting. However, its application can often be too complex to use as the basis for an immersive, capacity-driven, business model-based experience. It is also probably not what the majority of audiences are looking for in an interactive narrative. Sometimes too much choice is either confusing or feels aimless.

TM: Right, one of the problems with a large number of predetermined possible endings is that it can become an exercise in variety for variety’s sake over a coherent, satisfying narrative. As a participant, being constantly bombarded with choices that you know decide your ultimate fate can become a burden rather than a pleasure.

The amount of choice can feel paradoxically oppressive and unfulfilling.

There are definitely some types of stories and contexts where this multi-branching narrative model can work. Depending on the experience, it can add a big dimension of repeatability for the audience. For the most part, though, I’d argue that if you want to offer your audience truly endless possibilities, you’re better served crafting an emergent narrative experience. One where the environment enables participants to create their own stories organically and in real-time.

They aren’t forced down ever-branching rabbit holes. There’s an open-endedness and spontaneousness to the play.

The true open-world map

LA: The last narrative format I wanted us to mention is a truly open-world structure. This format is totally or very nearly totally nonlinear.

In this narrative, a participant possesses the unlimited freedom to roam the landscape. They can approach different story nodes from a variety of angles. One reason I want to highlight this structure is that it’s a format that lends itself to existing real-world locations. It allows for the possibility of participants self-directing around a destination as they like. While also still being part of a narrative.

The narrative isn’t necessarily directing their movements through the space. They’re engaging with the narrative in a way that meshes with how they want to also experience the destination, moving freely at their leisure. It’s a kind of narrative structure that could be deployed in a museum, zoo, city, or mixed-use resort destination.

The stars of the experience

You could describe an interactive theatre production like Sleep No More as an open-world interactive narrative. In Sleep No More, audience members are free to move about the physical space of the “McKittrick Hotel” set as they wish.

The next evolution of that kind of experience is making the audience feel less like an audience and more like the characters driving the story. They are the stars of the experience

The next evolution of that kind of experience is making the audience feel less like an audience and more like the characters driving the story. They are the stars of the experience.

TM: I’d add that the kind of interactive open-world narrative we’re describing would definitely need state-tracking. This ensures a clear sense of how the narrative and the participant is moving forward towards a larger goal. When a lot of the story content can come in any order, you need some way to measure and manifest the progress toward a satisfying conclusion.

I also think it makes a huge difference if the experience shows it knows where you’ve been. That means the order in which you do things can still feel consequential and not just like you’re checking boxes until the end.

LA: I agree. The more specific and personal you can make an experience feel, the more meaningful it becomes to the participant.

How important are multi-branching narratives for interactive storytelling?

TM: I’m not entirely convinced that branching tree structures are the be-all-and-end-all for the future of interactive storytelling. As we touched on in part 2 of our discussion, branching tree narrative is a complex form of design.

The game designer and author Chris Crawford criticized branching tree structures as being incredibly complex to construct while at the same time not delivering the kind of true richness of experience and spectrum of choice we would hope for as creators and participants.

I wonder if the future of interactive storytelling—rather than predetermined branching storylines authored by designers—might be in AI-assisted creations and procedurally generated experiences. For instance, Dwarf Fortress or AI Dungeon or the next generation of those games.

Multi-branching narrative – the more choices the better?

LA: In the industry today, I’ve noticed a knee jerk reaction. Everything has to be overtly interactive, and the more choices, the better. However, destinations and designers need to question those assumptions. They should take a good long look at who and what they are designing for when integrating these structures.

We need to recognize that choice does not necessarily equal great storytelling—even great interactive storytelling.

As for Chris Crawford, I admire his desire to push for a new standard of interactive storytelling. I think what he’s reaching for, though, is just one particular ideal of interactive storytelling that is further down the road. The current audience and technology are not quite to a point where we can deploy and leverage all of these offerings effectively. We need to test, iterate, and evolve this interactive artform.

We need to recognize that choice does not necessarily equal great storytelling—even great interactive storytelling

In Crawford’s case, it’s arguably a case of the quest for the perfect obscuring the good. He’s looking at the branching tree format and designed narrative as a limitation rather than the legitimate parameters of an emerging art form.

I would agree that multi-branching narrative is only one facet of interactive storytelling and not necessarily the endpoint. That said, it’s still, by far, the most prevalent interactive narrative device in use currently. It remains one of the best methods to craft an interactive story that has both choice for the participant and a larger narrative story arc.

Location-based interactive narrative: making it work

I’d add that transmedia narrative storytelling in a destination context is still in its infancy. Destinations and attractions still lag far behind the storytelling sophistication of the best video games.

That’s why it’s so important that we master the ability to tell multi-branching narratives well. We need to understand what works in these new contexts and what audiences want from new experiences. We need to explore and iterate what works in various applications, contexts, and mediums. That will help us to use these tools in the most compelling way possible.

There will be vastly different applications for the uses of AR, VR, cosplay, in a museum, park, urban setting, residential home, or theme park, etc. We are learning to walk, soon we’ll be running.

TM: Sure, and there are also many great games where a major part of the satisfaction is that you are guided within the framework of a story. There are predetermined pathways that lead somewhere of consequence. You can be confident that you won’t wander too far off course. And, as we mentioned previously, many gamers want a story that they can play through and to a definitive ending.

LA: That’s right. A multitude of different outcomes is not necessarily what everybody wants from every experience. It can be an exciting selling point. It’s not the only way to do it, though.

A balancing act

TM: The big balancing act in interactive storytelling is between freedom of choice for the participant and narrative meaning—a satisfying story. Too much freedom without consequences, constraints, or unfolding meaning, you’ve lost the appeal of narrative; too much narrative rigidity, you kill the interactivity.

Most games feature linear or predominantly linear narratives that you play through established story beats in order. Think about classic level-based platform video games, like Super Mario Bros. That sequential model is true of many games, even some of the more sophisticated story-heavy games. The interactivity doesn’t extend to altering the overall shape of the story.

We are sense-making animals. Stories are our primary mental tools for that act of sense-making.

“Shape” is a key quality when it comes to story. A major reason that story satisfies us is that it has a sense of shape. Whether it’s a linear or non-linear story, there are meaningful boundaries to what it chooses to include. It connects the dots to form a larger picture.

There’s a rising action and resolution, or a series of rising actions and resolutions and some sense of a beginning, middle, and end. Even if the chronology is scrambled or the order of events is in some way up to the participant.

There’s a big narrative and likely many mini-narrative possibilities within it that work together. It’s not just randomness. There are unifying characteristics. We are sense-making animals. Stories are our primary mental tools for that act of sense-making.

In Part 4, Alfieri and Madison investigate an idea put forward by the media scholar Henry Jenkins about interactive design as narrative architecture. Jenkins looks at games as being different kinds of narratively compelling spaces that a player travels through. It’s a perspective that’s especially resonant for anyone who creates interactive experiences for real-world destinations.