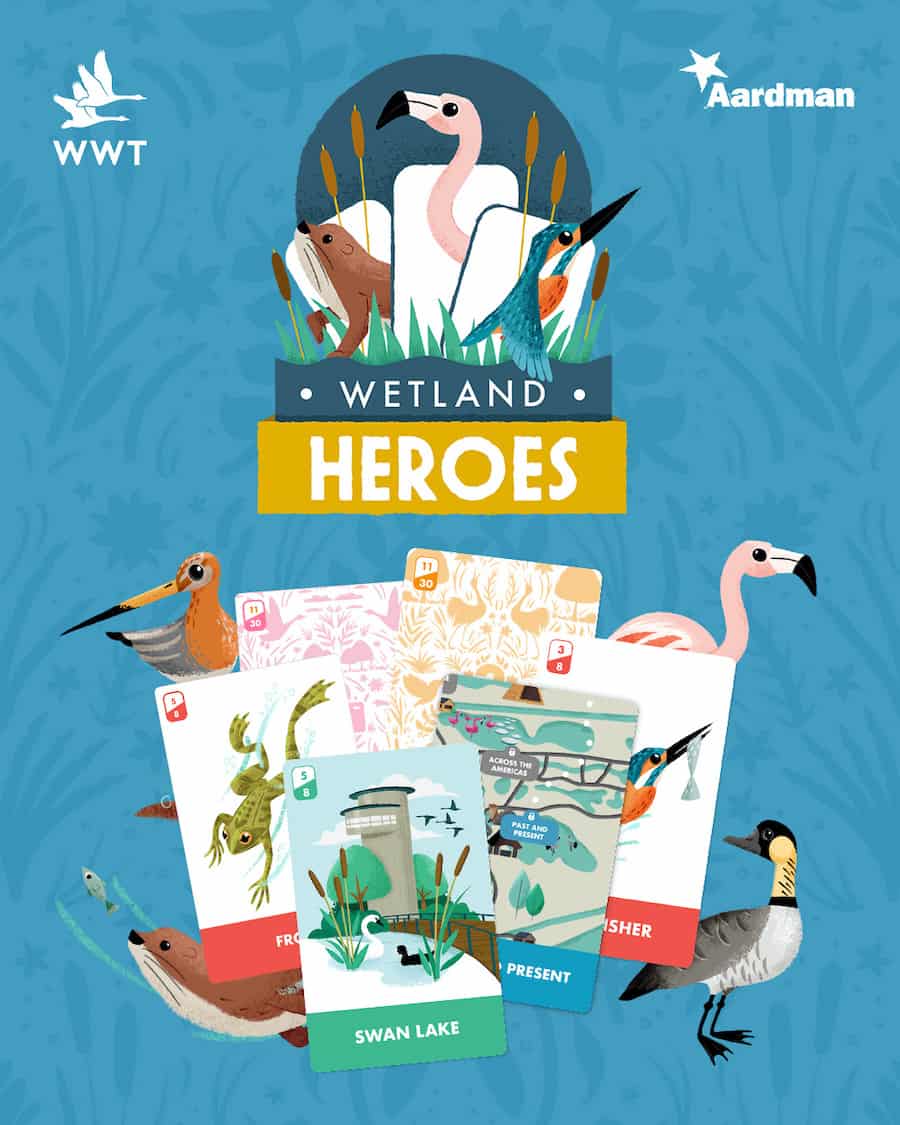

Aardman, the award-winning UK studio, has partnered with WWT Slimbridge Wetland Centre in Gloucestershire, UK, to help connect families with wildlife through an interactive mobile app called Wetland Heroes.

The app, a digital enhancement to the visitor experience, represents the diversity of wildlife at the centre. Through fact-finding missions and fun challenges, the app highlights species including flamingos, otters, swans and kingfishers through beautiful illustrations.

WWT Slimbridge, opened in 1946, is a wetland reserve near Slimbridge village in Gloucestershire. It was the first of the nine Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT) Centres in the UK to be opened and is home to a diverse array of wild birds and creatures, as well as a zoological collection.

Daniel Efergan, Executive Creative Director of Interactive at Aardman, Mark Burvill, Technical Director of Interactive at Aardman, and Fran Penny, Visitor Experience Manager at the Slimbridge Wetland Centre, talked to blooloop about the collaboration.

Slimbridge Wetland Centre

Fran Penny is the Visitor Experience Manager at the Slimbridge Wetland Centre, overseeing all the visitor-facing teams and operations: admissions, learning, engagement, and marketing.

Outlining the Centre’s function, she says:

“Slimbridge Wetland Centre is one of nine Wetland Centres run by the Wildfowl Wetlands Trust (WWT). We are the flagship. WWT works nationally and internationally to save wetland species and habitats.

“Our visitor centres provide a key way to engage visitors in wetlands and their importance. When people visit our centre it helps fund our conservation work both in the UK and across the world.”

The Centre attracts a mix of visitors:

“We have our birders and wildlife photographers who head out into the wild areas of the site – we’ve got a large nature reserve. They sit in the hides and look for the rare and visiting birds. Then there are people coming for a nice day out, social visitors looking to visit with friends; couples, and lots of family visitors, which is where the app really comes in.”

“Family visitors come for an educational learn-together type of visit, or, in the middle of the summer holidays or at Easter, just for a fun day out. We’ve got playgrounds and a canoe trail, as well as the wildlife.”

Wetland Heroes

“The Wetland Heroes app is part of a project we’ve been working on over what will be four years now, because of COVID,” says Penny.

“Slimbridge 2020 is a large, funded project supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. One of the aims was that we wanted visitors to explore off the beaten track. We wanted to try something that used a bit more digital engagement. Because it allows us to engage with a wider audience that hasn’t been given those kinds of opportunities on this site before.

“The overarching aims of the project are about connecting people with WWT’s conservation work, its stories, and some of the stories about the species.

“The facts and figures built into the app are an easy and digestible way people can start to understand a little bit more about the natural world around them and be prompted to want to take action and do more.”

A passion for nature

Dan Efergan, Executive Creative Director of Interactive, has a background in supporting young creative people across the Southwest of England. He also used to run a creative boutique, and has been involved in “weird and wonderful things, always involving creativity and computers.”

Efergan has been at Aardman Animations for 12 years. He says:

“I’m Creative Director for all the interactive and gaming stuff we do. I helped the team form and grow and become what we are. I was a coder originally, so my trade is making computers do things. When I joined Aardman as Creative Director, people couldn’t work out why I couldn’t draw.”

Of the Wetland Heroes project, he says:

“What I found so encouraging about our experiences of working together was how much the Slimbridge team understood about the people who went there, and how deeply embedded their passion for nature was.”

“It was interesting how the two groups of visitors that they talked about interacted, the very hardcore bird-watching nature lovers, whose environment involves peace and solitary existence, and who might find even another twitcher nearby frustrating, and the families with young children, with three-to-six-year-olds running around. What was nice was that both used their powers for good.

“There was the holistic question of, how do we bring everyone in? How does everyone enjoy this experience? But then the people who loved nature were so desperately passionate about trying to convert those other visitors into nature lovers.”

A wide audience

Penny adds:

“The layout of Slimbridge naturally creates zones. The nature reserve is out on the fringes, looking out towards the Severn Estuary. That tends to be where the bird watchers, photographers and those people looking for some peace and quiet will gravitate towards.”

“The areas around the visitor centre, our collection and our zoological collection, are where families tend to be.

“There is a bit of natural zoning, but also, and this is one of the things we want the app to do, is we don’t want people to feel that there is this invisible barrier. That, if you’re a family you’re not allowed to go out into the wilder areas, and the other way round. Part of the app is involved in getting people to explore those wider areas.”

Testing Wetland Heroes

Mark Burvill, Technical Director of Interactive at Aardman, was involved in all the technical decisions around the Wetland Heroes app, working with developers and testers to build it.

“Slimbridge is quite spread out; the bird hides are quite far away from the centre,” he says. “One of the things we wanted to do with the app when we were in the design process was to give people a reason to get to bits of the site that they hadn’t visited, or didn’t even know was there.”

“When we were doing our user testing with some groups of families that were regulars to Slimbridge, it was really nice that some of them were saying, ‘Oh, I didn’t know this part was here. I’ve never really been to this area.’”

Why an app?

Touching on the genesis of the app, Efergan says:

“We had a pyramid of attention. At the very top level is becoming a sponsor, taking best practice back into your own life, doing things in your own garden, being a fully converted member, saving and supporting wildlife; at the bottom are the people who just want a nice day out somewhere. Our goal was to capture that bottom rung and move them up one level.

“At the beginning, we asked everyone at Slimbridge why they were dedicating their lives to conservation.”

“Most of them could talk about a specific, magical moment – the time they saw birds do this, or a morning at dawn when that happened, or they saw chicks and fell in love with them. They were very specific things.

“We were always trying to create an opportunity for one of those moments to happen.

“Many of those moments are about being in the right place at the right time. But this way we’re trying to create opportunities for those things to happen.”

Wetland Heroes app needed to add to the experience

A key challenge lay in preventing the Wetland Heroes app from becoming a distraction from the wildlife and the experience.

Burvill says:

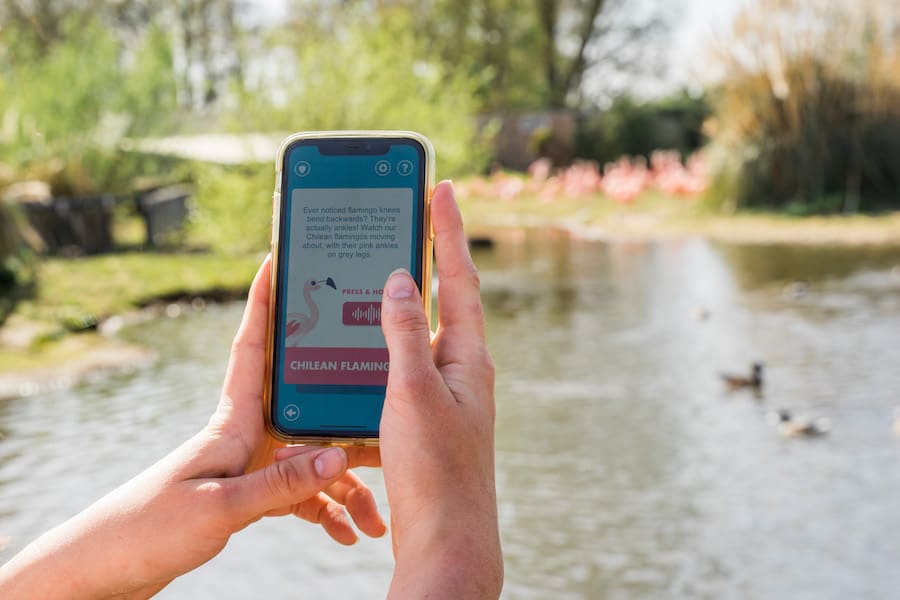

“It’s always a concern with things like this. You don’t want to encourage kids to be walking around on their phones the whole time. Especially at Slimbridge, because there are lots of bits of water that you can step into or fall into if you’re not looking where you’re going.”

“We don’t want to turn attractions into an experience where you’re just on the phone the whole time. We want to circulate people around through gamifying the process a little bit, but where the app is encouraging them to look at what’s around them and to learn a bit more about what’s around them than they might have otherwise have done.”

Delivering information

Efergan adds:

“The app’s solution is nestled in, or directly related to, the problem we were trying to solve. It’s a problem that comes up if you’re doing anything location-based, where you’re driving people around the space. We’ve done it in museums; with the Science Museum, and Bristol Museum, which had a similar problem.

“We all know how compelling and all-encompassing a screen can be. Once you’re in that world, you’re stuck. So when you’re trying to use something as a torch, a bit of knowledge to help you around the space, you’re always fighting with how to convey information, but then get people to put the screen away.”

“That problem sits in a few different places. How often do you deliver information? How do you deliver information? Where possible, we would have loved to have made it an audio experience, because that’s one of the best techniques you can use.”

However, headphones would make it a very personal, individual experience:

“This is a family experience, so that was a dead-end. We couldn’t use audio as the transfer medium.

“Ultimately, we got to the conclusion that we wanted to push people out to explore more; to see more; even to see more in places their eyes were already looking, because when it is connected with knowledge and understanding and behaviours and colours and all those things, it suddenly means so much more.

“The most effective technique to get that out to people was to put it on their phones.”

Less screen time

However, understandably, many of the people visiting the park were going there to avoid screens: “Families were getting their kids off screens, and going for a day out together,” says Efergan. “We had this oxymoronic situation of trying to use a screen to support people to get off screens.”

With an app where there are charismatic representations and animations of wildlife, there is a risk they will distract from the actual wildlife, which tends to be likely to stay out of sight where possible.

“Some of the hero species that the Wetland Heroes app focuses on can definitely be hard to see,” Penny says, “But then there are others, like our very large flocks of flamingos, where you can’t help but spot them.”

Efergan adds:

“Apart from a little bit of celebration at key points, the app then goes quiet. And it doesn’t really do anything else. This is why we went for the slightly inert metaphor of the pack of cards. We tried to keep our work peaceful, calming, and illustrative.”

Wetland Heroes enhances the interaction with nature

The idea is to enhance the interaction with nature, rather than distracting from it.

“Each card asks you to look out into the park,” says Efergan. “That’s probably the most important thing. If you are engaging with it, and you actually do what it is asking you to do, each one is, ‘Can you see this? What happens if you do that? Have you found one of those? Where is that thing? Why not go and hunt it out?’

“The most phone-y thing is ‘Let’s take a picture of you and your family acting like fools.’

“In that way, every action brings you back into the world. I cannot deny that phones have their own traction, because I have an 8-year-old son.”

Overcoming challenges

Burvill says: “When we were first experimenting and throwing ideas around, we were looking at using GPS positioning. But, because it’s a fairly small site and some of the checkpoints we wanted to get to were quite close together, it wasn’t really sufficiently accurate.

“We were really struggling with that. We were also noticing that in really early testing the users were using the phone as a scanner. They were walking around trying to get themselves in the right position and were on the phone a lot more. That is why we backed away from that and went instead for the scannable AR markers that we’ve used. These are quite visible, and they’re quite distinct.”

“It’s a method that gets users actually looking up and around. They are doing more of a treasure hunt for those, rather than looking at a map and their position on the map the whole time. We also didn’t want to have to rely on GPS or Wi-Fi signal. It’s a remote spot, so you can’t guarantee everyone is going to have the same accuracy on their phone.”

Look up

“It was in the brief from the start that we didn’t want people looking down at their phones all the time,” Penny says. “Encouraging looking up has worked really well.

“Having to look for the actual physical markers allows you to put your phone in your pocket. Then you look up until you get to the next marker. And then you engage with it for a very small amount of time. You don’t have to have the phone out the whole time.”

Burvill agrees:

“There is a map in the Wetland Heroes app, but it’s not front and centre, deliberately. It’s kind of tucked away. It’s not made an important focus. We wanted people to naturally walk around and look where they’re going.”

Navigation

Efergan expands on this:

“The map becomes a really key and interesting problem, and navigating your way around a space, because to some degree the navigation of a space is a wonderfully engaging process. You have to look at stuff, and check signs. You have to build a mental model of where you’re at and what’s around that corner.

“So many treasure hunts appear in these formats because you’re trying to draw people to different parts of an experience. Treasure hunts and maps are intrinsically linked. It’s an interesting problem in terms of what you do with a map. “

“When we were experimenting on this – we were working with Bristol Museum at that point – we went from having a map with a dot on it to having a map without dot, to having a compass that pointed you to the room that you should be going to, eventually throwing all of it away and saying, ‘Go and find the Egyptian room.’

“And that was it. We had to get rid of everything. We ended up doing the same a bit with this, stripping it back until we got rid of the map. But people still wanted to know about the park.

“By downloading the Wetland Heroes app, they assumed that they didn’t need to pick up a paper one. So we ended up copying the paper map. It doesn’t show you where you are, but it shows you where you can go and experience stuff. It’s interesting how we build products to do something, and then spend loads of time stripping everything out to stop people looking at it. It’s a weird problem.”

Social interactions with Wetland Heroes app

The solution was effective:

“The desire to get to the next spot worked really well. Kids took over. They took the phone from their parents and took over the navigation. From all the user testing and experiments we did, you could see them enjoying that empowerment, directing the way; using the map in that treasure-hunt drive to get to the next place.

“That was positive. The fact the Wetland Heroes app doesn’t give them anything to do on the map meant that although initially, they were holding onto it, they did then put it away.

“The downside is we don’t have full control over phones. So, I witnessed, at least a couple of times, kids then moving out of that app and going to something else. That is exactly what the parents don’t want.”

“There is always this argument about making it a piece of paper with which they can’t do anything else. But where I saw the benefits was in the activities – the camera filters, the trivia where one person has to ask other people questions, forcing interaction between the group; those are the things that brought the family together.

“Those social interaction activities worked well. You have to be an active participant, but it’s amazing how many families are there to have fun. We also noticed young couples and friend groups were up for it, as well.”

Long-term visitor engagement

In short, Burvill says

“It was all about making it a social thing, rather than a stuck-on-your-phone-and-following-a-dot-around-the-map thing.”

In terms of longer-term engagement, he says:

“We have a system of achievements in the Wetland Heroes app; badges that you can win, and that encourage people to come back in different seasons throughout the year.

“You get a badge if you visit during the spring or winter or autumn. This encourages people to see the site as it changes over the year. Because it is one of those places where you’re going to see something very different if you go at different times of the year.

“We keep it so that the things that you have unlocked while you’re on the site, you can go back to and have another look at while you’re at home afterwards.”

COVID restrictions

One of the challenges that Slimbridge faced, from an operational point of view over the last year, was COVID and the lockdowns.

“By the time we came to launch the app, not every single area was able to be open because of some of the COVID restrictions,” says Penny.

“In fact, I think the app worked in our favour there. Because what we were able to do is move the checkpoints ever so slightly in front of the area that had to be closed off, and use it to tell the visitors to use the app to unlock some information about the animals in this exhibit.

“Even while they couldn’t physically get into it because of restrictions outside of our control, they could still use the app. So they could find out some interesting facts and engage with those areas. It’s been an unexpected positive use of the app.”

Discovering Slimbridge through the Wetland Heroes app

Slimbridge has eight areas which the app unlocks.

Penny says:

“For each of those areas, we’ve got a Hero species; one species that we highlight. They are quite recognisable species that we picked to feature in the app. In the area where we talk about mammals, for instance, the Hero animal is our otter. Out on the wild Reserve, it’s our Bewick’s swan, a winter migrant visitor for which Slimbridge is famous.”

“Aardman’s team did a beautiful job of turning those into little illustrated characters.”

“One of the hero birds is our eider duck. They make a fantastic sort of noise when they’re on site. The sound is also on the app. Our catering manager was testing out the app and he emailed me to say how much he liked it. His feedback was, ‘I now get to have an Eider in my pocket all the time.’”

The appeal of collectables

“The app mimics physicality as a slight selling point,” Efergan says. “It’s as if you’ve got a deck of cards in your pocket. Each card has some facts, figures, little games to take place that you can do around the park.

“But these packs have been hidden across the park. So you have to explore the park, find and scan a sign that gives you eight to 10 little ‘cards’. These include trivia, sounds, and little challenges that involve going out and finding stuff. Or silly frames so you can take pictures of yourself doing silly things in different situations.

“Our intent was to give people some very snackable tiny things to look at quickly, and then put the device away, so they could see the world in a slightly new way. So that was our start design.”

Burvill agrees:

“The idea of turning Wetland Heroes into a collectable card game was one that came up quite early.

“All kids love collecting things. You show them a locked box of things then tell them how they can unlock it, they have to unlock it, and won’t rest until they’ve done it.

“It felt really nice to hark back to top trumps, and trading games, and modern card-based mobile games. It seemed a very natural, fitting thing to do. We liked the idea of having these hero species in the areas with the things that you have to collect and find.”

Digital trends

It is interesting to speculate whether, post-COVID, connection with nature and conservation experiences will become digital trends.

Burvill says:

“Throughout the lockdowns, people have turned to their devices for entertainment and for the limited social functions that we’ve been able to do. We would have been so much more isolated without that ability.

“The flip side is that we’ve all spent far too much time on our phones. But I, for one, have got a lot of value out of using apps that show me the local trails I can go and walk around. There is an app I’ve been using to uses AI – you can scan different plants and it will tell you what they are. As AI improves, the ability to identify wildlife and plants is amazing.”

“There is always a balance to be drawn between too much screen time versus the opportunities offered by screens. I think we’re in a good place where we’ve learned how our devices can bring a lot of extra benefits to being outdoors, exercising, exploring new areas, identifying new bits of wildlife, and learning about the world around.”

“People have really come to appreciate exploring their local areas and being able to connect to nature, “says Penny. “Using digital tools to be able to find out more about things allows for that extra level of enhancement. It also allows people to engage a little bit deeper.”

Technology develops

Efergan says:

“It’s an interesting one; because of COVID, we have seen both the pros and the cons of being digitally connected with people.

“You could argue it both ways. You could say that since people are going to spend so much more time in digital space, they are going to want their retreat to be technology-free. Or you could argue that we’re going to be more accepting of technology.

“My instinct is that the digital processes are going to become more pervasive, and will disappear more into stuff, and when that happens, when people aren’t so directly locked on a tiny screen, and, potentially – I’m going to make something up here – you could see little digital arrows pointing out exactly where the animals are, if you want to, then we wouldn’t feel that it’s quite so invasive because it would feel more part of the world.”

“I think we’re going that way. It’s just that right now it’s quite clunky. So, our window into this world is this horrible little shiny screen that also has games on.

“In a Children’s Media conference, probably 10 years ago, I said that my personal passion was that I would love to see all that enthusiasm and excitement you feel playing against your friends in an online game to invade outdoor play.

“Why can’t we be running around the woods with a sword in our hands, but actually still be able to play with your mate in another country at the same time? And get scores and have leader boards and all those things that make us want to do it? That’s a kind of underlying dream.”

Connecting to nature post-COVID

People will, Penny feels, become more aware of nature and conservation experiences in the wake of COVID.

“There’s definitely overall a sense from visitors and volunteers returning to the site that they are just so pleased to be able to get back here and spend time outdoors. They value it now a little more.

“There’s some really interesting research about nature connectedness, by the University of Derby. This shows it’s the level of connection you have that is important, beyond just spending time in nature; identifying a plant, or doing some gardening or bird watching. Connecting with nature at that secondary level is almost more important than the time spent.

“There is research going on in the background, too, that shows people want to engage more. Maybe it’s partly about realising that there are links out there between things like COVID and what we do with nature and the planet.”

In conclusion, she says:

“The Wetland Heroes app has helped us with those general aims that we have as an organization. Our aims to get people interested in wetlands and valuing them and wanting to do something about them. It’s another tool we now have to now pursue that on-site here at Slimbridge.”

The Wetland Heroes app is now available to download for both Android and Apple devices.

Header image: Andean Flamingo – Credit WWT, Rebecca Taylor