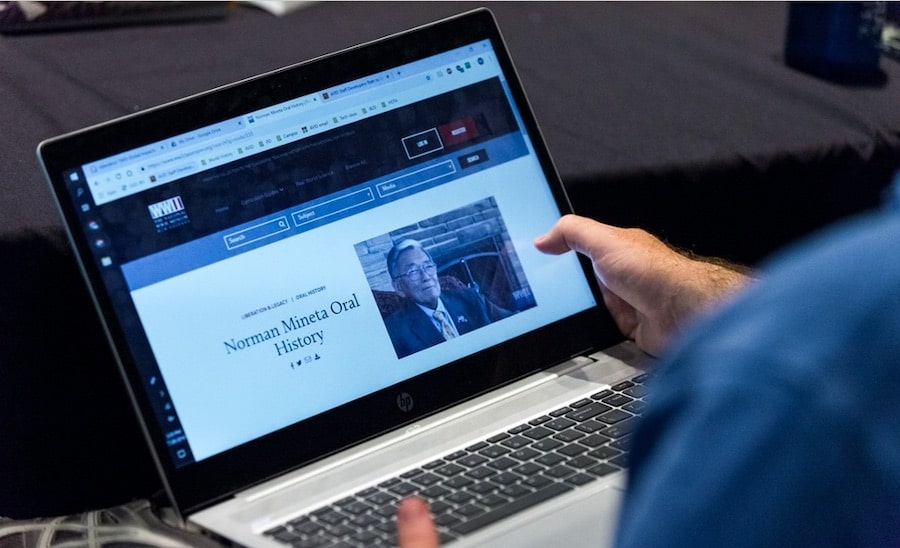

Elizabeth Merritt is the American Alliance of Museums’ (AAM) VP for Strategic Foresight, helping the organisation navigate the unwritten future using futures studies such as scenario development, horizon planning and trends analysis.

The author of AAM’s annual TrendsWatch forecasting report, Merritt is also the founding director of the Center for the Future of Museums (CFM). This is an influential think-tank and research and development laboratory focused on the development and future-proofing of museums.

Prior to starting CFM, she literally wrote the book on museum standards and best practices, as director of the Alliance’s accreditation and excellence programmes, perfect preparation for her current role as agent provocateur—challenging museums to question assumptions about traditional practice and experiment with new ways of doing business.

She spoke to blooloop about TrendsWatch 2021, as well as some of the topics she will be speaking on at AAM’s annual conference.

#AAM2021 takes place on 24 May and 7 – 9 June. It will feature three keynotes and three Elevate Stage sessions, as well as over 80 concurrent sessions, more than 30 poster presentations and 15 networking events.

Future planning for museums

One session that Merritt will be presenting at the conference is ‘Living in the Future: A Guide to Scenario Planning for Museums.’

She says: “One of my pitches for why museums should do strategic foresight is that, to quote the writer William Gibson, ‘The future is already here – it’s just not evenly distributed.’

“If you spend time thoughtfully looking around, you’ll see little clues, signals of things that might become mainstream practice in the future. By being aware of them now, you can become an early adopter. Or be better prepared to adopt it when it becomes right for your organisation.”

The future is already here – it’s just not evenly distributed

“I have said before, semi-humorously, that nobody expected the pandemic. But actually, plenty of people expected the pandemic.

“At the beginning of the Center for the Future of Museums (CFM), we addressed how to engage with online gaming. One of the first things we did was to lead museums in a massive online multiplayer scenario game created by the Institute for the Future. This was about what it would be like to live 12 years in the future.”

One of the main premises of the scenario of that game was a global pandemic.

“In the game, museums had to figure out how to manage their programme within the government limits on how many people could be in a place at one time.”

Scenario planning

“Scenarios can help anyone foreshadow the future,” says Merritt. “What I have been promoting is that they are useful for museums.”

“If museums keep in mind that there are many potential futures, and, at any given point in time, they are all potentially in play, rather than trying to create a plan that would work perfectly if only this one thing happened, they should engage in more flexible and adaptive planning.”

“If scenario A happens, this would work. Or, if B happens, it will work with that, too. That way, you’re not putting all your markers on one assumption that turns out to be wrong.”

Future strategies for museums

This goes beyond contingency planning:

“It is planning that identifies strategies that could be successful under a whole range of different circumstances. It’s rather like the way in which universal design ends up being good for everybody. Curb cuts are not just good for people who are using wheelchairs for mobility; they’re good for everybody. They benefit parents with strollers, and people dragging suitcases, and kids riding bicycles.”

“Similarly, there are strategies for museums that are good under a whole range of circumstances. For example, ‘We took into account that maybe our city wouldn’t get this major contract for expanding the airport, so international tourism would go down.’

“International tourism can go down for a lot of reasons – including a global pandemic. If you look at the overarching challenge, we are very dependent on tourism. What could we do that helps to weaken some of that reliance? Then you can come up with strategies that might come into play for a number of different reasons.”

Changes ahead

The problem, Merritt concedes, is that there are so many challenges:

“We’re now crashing, rather than easing, into a century that is going to be full of profound disruptions.”

“You can’t separate this pandemic from the challenges of climate change, and climate change is creating all sorts of challenges. Climate change is going to make pandemic disease more likely and more frequent. In addition, it will also increase the rate of displacement and migration caused by climate emergencies. It will create more disasters from severe storms, severe heat, and severe cold events.”

Responding to challenges

“A couple of months ago, I was talking with the Board of a museum in Texas,” says Merritt. “I gave a little exercise on thinking about the future. We played a little game where we said, ‘What if you woke up tomorrow morning, and some severe climate event had shut everything down. How would you respond?’”

“A week later, Texas has this phenomenal deep freeze that disrupted disruptive power. Everybody was huddling in their houses against the cold, without power. The museum, which didn’t lose power, was opening itself as a warming shelter for the community.

“It is easy for me to say this,” she admits. “It’s my job to spend all my time thinking about these things. The challenge is how to create materials that help museums do this work. Without having to become futurists themselves, or needing a full-time futurist on staff. That is where things like these scenario sets come into play.”

Navigating uncertain times

The session will explore the importance of scenarios, profiling a Scenario Planning Toolkit funded by the Wallace Foundation. This is called Navigating Uncertain Times.

“One of my speakers is from the Wallace Foundation, and one is from AEA Consulting, which published the scenario set. The set looks at how the pandemic could play out, when and how it ends, and how society responds to it. More generally, it’s promoting the habit of futures thinking and taking a broad and imaginative approach to what the future could be like.”

Merritt was happy to be able to recruit molecular and cellular biologist, data architect, and multidisciplinary artist Ash Baccus-Clark:

“I first met her because of a project she did in collaboration with colleagues at a practice called Hyphen-Labs. They came up with an immersive virtual reality installation, NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism.

“The installation envisioned alternative pasts and alternative futures around African-American and black identity. If you bring in people from outside the field who are artists, who are technologists, who are visionaries, they can enrich and broaden your vision so that you don’t get stuck in the same set of assumptions that tends to guide your traditional planning, and make it equitably accessible.”

The digital divide

One challenge that has been exacerbated by the pandemic is the digital divide. This is the gap between who has technology or access to high-speed internet connections, and who doesn’t.

“That,” Merrit explains, “has turned out to be one of the drivers of educational inequities during the pandemic here in the US, as schools pivot into online instruction. There is a similar danger that as museums put more and more effort into creating rich and enriching virtual experiences in the future, they need to also be thinking about equitable access. So that they’re not only serving a small group of people who can take advantage of that material.”

Conversely, there is evidence suggesting that digital resources might close some of the gaps in racial and educational equity.

“Research was published relatively recently by Slover Linett Audience Research and LaPlaca Cohen, who have been running Culture Track, a study of public engagement with culture organisations, for many years.”

Why engage digitally?

Slover Linett and LaPlaca Cohen have just collaborated on a national research and strategy initiative, Culture and Community in a Time of Crisis, to support the cultural sector and help strengthen communities around the US during and after the COVID-19 crisis.

Merritt explains:

“One of the things they explored was how people were engaging with culture and arts organisations online. They found that a lot of people who didn’t traditionally attend those organisations, including museums, in-person were using their digital offerings. Digital resources seem to have increased access by parameters such as race and education that have traditionally been a predictor of in-person audiences.”

“My follow-up question, focusing on those people who weren’t attending in person, but are engaging digitally is – why?

“Is it time and accessibility? It’s easy to get on a computer at night and use it to access an online programme. As opposed to getting in a car or bus to travel across town after work before the museum closes.

“Is it because of logistic issues like that? Or is it psychological and cultural issues? Does the physical space seem intimidating or unwelcoming, whereas online engagement offers a degree of anonymity? Is it that the online materials are more findable; people come across them and are familiar with the format?

“It’s really promising. It raises as many questions as it answers about why some digital offerings may be more accessible and used in a more equitable way than the physical offerings.”

Contradictory research

Results of research into why some sectors fail to engage with in-person visits to cultural spaces are contradictory:

“There was a very interesting research project done five years ago, now, by an organisation, Createequity, focussing on arts research. They published an article, ‘Why Don’t They Come’, summarising research that they had mined from sources. These included the ICPSR National Archive of Data on Arts and Culture, the BLS’s Consumer Expenditure Survey, the National Endowment for the Arts, and some government data.”

“They asked the question, ‘how much of the gap in arts participation was due to income or availability of leisure time, as it corresponds to socioeconomic status?’

“I’m not attacking or endorsing this. I don’t think I’m qualified to judge, not having dug into their methodology and the data. But their conclusion was that if every exhibit and performance in the US could be attended for free, that would only bridge 7% of the gap and attendance between rich and poor, or between people who attended college and people who didn’t.”

Even eliminating transportation barriers would, the article maintains, leave a chasm in arts participation between people with low socioeconomic status and the rest of the population.

“Their conclusion,” Merritt says, “was the biggest reason, the factor that most strongly correlates between people with low socioeconomic status who are not visiting museums is they’d rather watch TV. It is preference about what is an attractive use of leisure time, which is pretty depressing.”

Filling people’s needs

Does this mean museums are failing in engaging these audiences in a compelling and relevant way?

“But the Culture Track study is suggesting the opposite; that when you go online, it evens out some of that inequity. Maybe it’s the difference in methodology.

“Something the survey claims is the government data shows that people with low socioeconomic status have more leisure time.

“I always try and poke holes in people’s research, just to keep everybody thinking about it. My question is when you say ‘leisure time’, does that take into account all of the things that people with low socioeconomic status have to deal with just to navigate through the world? For instance, figuring out how not to get evicted for their rent, or caring for others?”

“Those factors take real time and eat into your emotional and cognitive energy budget. So, they may erode what is considered to be their ‘leisure time.’

“Something I would like to encourage museums to think about, and it is something TrendsWatch has addressed over the years, is pivoting from framing it as ‘how do we reach these different groups with what we do?’ to, ‘what do people need and want and how can we adapt our resources to fill those needs?’

“It is a very different question that is more in service to, and less framed as marketing.”

Museums & older adults

Merritt will also be exploring the topic of ageism when she speaks at The Museum Summit on Creative Aging on 29 July 2021. Since 2018, AAM has partnered with the Aroha Philanthropies to develop ways museums can address ageism and serve older people through specialised programming and public education in the future

Here, she explains why ageism is an important issue for the museum community:

“The National Endowment for the Arts in the US conducts a survey called Survey of Public Participation in the Arts. And there is a strategy and marketing firm for the creative and cultural worlds, La Place Cohen, that has worked to do a regular survey over the past few years called Culture Track. This examines public participation in public-facing organisations like museums.”

“Both of those sources suggests that only about 17% of people aged 55+ visit museums at least once a year.”

There is, clearly, an opportunity for museums to increase their reach among the older audience:

“It would be logical to target them. In general people at that stage of their life and career have more time and, hopefully, resources to enjoy what museums have to offer.”

Tackling ageism

Ageism is a problem in the museum sector, Merritt explains:

“I’m a great believer in the fact that we should look at museums in the context of overall society. Ageism is a problem in society, so it’s no surprise to find that it’s a challenge in museums as well. There are many negative effects of stereotypes about ageing which help to increase social isolation, which is already a problem.”

Ageism is a problem in society, so it’s no surprise to find that it’s a challenge in museums as well

“There are, of course, documented challenges with ageism in terms of discrimination in work and employment. This is a particular issue in the US. Here, the demographics show that by 2035, Americans over the age of 65 are going to outnumber those who are younger than 18. That is a very extreme age skew.”

Museums, she maintains, need to respond to the needs of their audiences:

“It has been shown that arts and culture engagement can have tremendous positive effects on health and ageing. It is an opportunity for museums to serve this growing population. Everybody will age into that cohort. Everybody should care about this.”

Broader educational resources

Educational resources need to be broadened to accommodate both ends of the age spectrum.

“The vast majority of museums’ commitment of time and money to programming and education goes to K–12 students. This is great; I’m not suggesting they cut back on that work. But imagine if they devoted comparable resources to people at the other end of the age curve. Especially when you consider how the population is distributed at end of the age curve in coming decades.

“It goes back to what I was saying about museums inheriting the challenges, bias and structural inequalities of the culture writ large. There’s a whole government agency devoted to K–12 education. Meanwhile, the semi-comparable agencies devoted to older people are all about, ‘do you need support because your health is failing?’ They’re not devoted to education, enrichment, and enhancing people’s lives.

“I am hoping to speak soon with somebody from the AARP (formerly called the American Association of Retired Persons) here in the US. This is a private non-profit foundation run for, and by, older people.”

Creative ageing programs

Identity and perception play a role in how older people are viewed and included:

“The initiative that we’re engaged in right now is looking at everything from awareness of ageism and the challenges and opportunities of ageing, to how museums can promote equity in all facets of their operations in the future. There is employment, which is a legal issue, but also how communications depict older people.

“Our focus has been on creative ageing programs, and how these can help empower older adults to use learning an art form in a socially supportive setting as a way to feel that they are being taken seriously.”

“Artists teach these workshops. It isn’t just playing around with paint. It’s really learning something – writing, painting, or photography – and doing it in a way that that is sustained and serious. It is multi-part engagements where you can learn something in depth from a professional.”

Sharing is the second part of the process:

“This cohort is called Seeding Vitality Arts in Museums. Every workshop ends with a public presentation, either an exhibit or a performance of the participants’ work. It is something they can share with their community as well as their families.”

Building intergenerational bonds

Part of the strength of that, Merritt says, lies in building intergenerational bonds.

“For example, one of the cool programs that Seeding Vitality Arts supported was the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tucson. This already had a performance programme called School of Drag. They had older members of the LGBTQ community who came to them, saying, ‘Hey, this shouldn’t just be for kids. We should have one too.’”

“So, they put on some iterations of the School of Drag which connected elders and teens from the LGBTQ community. It was great, because that is, potentially, a double isolation. Being non-heteronormative and an elder puts you in a doubly socially isolated group.”

Sharing wisdom

Much of how ageing is playing out as a challenge in the US seems to be culturally specific.

She continues:

“We’re doing this with the support of a funder, Aroha Philanthropies, who developed a model of how to use creative ageing programs in a lot of different kinds of nonprofits. Talking to them, we said, ‘Wow: this is absolutely adapted for museums. Put this in the museum, and I’ll knock it out of the park.’

“It’s not only teaching arts, but it’s also teaching arts in a serious, respected arts environment. So people feel even more elevated.”

“Plus, it’s clear that doing it in a museum environment creates opportunities. For example, cross-generational mixing. And for a real recognition that one of the strengths that elders contribute to society is their experience, knowledge and wisdom.”

Another programme was developed by the Union County Historical Society and Heritage Museum, in New Albany, Mississippi:

“They were creating a series of workshops for their local community. They did a workshop on pottery, which is one of the great folk traditions in the South. One reason this resonated so much is their community was keen to preserve, support and share training in heritage crafts. And it was the elders of the community who had that knowledge. By publicising and honouring that, they can interest young people in learning these traditions.”

Financial motives

Two further points interest Merritt particularly:

“The first thing is that, in the US, museums are not primarily supported by the government. So, they have to worry about where the money is going to come from.

“I would also point out to museums here that, regardless of any other motives you might have for doing this – and there are many good motives – the baby boomers are expected to transfer $30 trillion in wealth to younger generations in the future, over the next two decades.

“Hopefully, they’re also going to be leaving some of their money to organisations they value and believe in. Museums have this opportunity to be a meaningful part of the lives of these people.”

“The second point is that at the start of this project, one thing we didn’t anticipate was the pandemic. It really impressed me how quickly and successfully, in terms of these workshops for older people, a lot of these museums pivoted to digital platforms.”

Countering ageist bias

There is, she points out, another ageist bias in that there was a widespread assumption that older people wouldn’t be able to figure out how to use a computer, navigate online or master Zoom.

The assumption proved false:

“It worked really well. A lot of museums found that they had many more people wanting to do these workshops than they could accommodate.

“They were finding that there are people who would love this kind of participation, who couldn’t come to the museum previously in person. They were reaching people who might be from the other side of the world. Or local people with mobility issues, one of the things that contributes to social isolation in older people.”

“I think one of the enduring changes that comes out of the pandemic is that more museums are going to be incorporating virtual elements, or virtual versions of this kind of interaction with older audiences in the future. Even after the pandemic fades away.”

The COVID lockdown period hasn’t so much accelerated innovation, says Merritt, as accelerated the adoption of technologies that museums were already trying:

“I haven’t seen much that is absolutely new. But I’m seeing more museums trying things they weren’t trying before. They are saying, ‘We want to learn from other museums that were already doing this, instead of having to work it out from scratch for ourselves.’”

Museums & community

Merritt argues that museums are a key part of the essential infrastructure that holds communities together.

This year, museums face rapid, transformative shifts on all fronts. In response, the newest edition of AAM’s TrendsWatch focuses on the issues museums should attend to now, to minimise harm to their communities in the future and ensure their own survival.

In the report, Merritt contends that museums are a vital strand in the complex web of nonprofits that holds together America’s patchy infrastructure of education, health, and economic support. As such, they can help protect those most vulnerable to the economic and psychological damage wrought by the pandemic.

There is a wealth of information and resources aiming to equip museums to navigate today’s unique set of challenges. This includes chapters like Closing the Gap: Redressing systemic inequalities of wealth and power; Digital Awakening: Essential technologies for pandemic survival and future success; Who Gets Left Behind? Caring for the vulnerable in a time of crisis and COVID On Campus: How the pandemic is reshaping higher education.

TrendsWatch & the future of museums

Selecting topics relevant to her previous conversation from TrendsWatch 2021, Merritt says:

“First of all, to go back to what we were saying about digital, reach, accessibility and audience. That is great for museums that are already set up to not only reach people digitally but to substitute some of the traditional income streams that have been completely disrupted with income from digital. That is a very small set of museums.”

A significant number of museums have been investing in digital platforms that can produce content. However:

“They haven’t been worrying about income. Then there are a fair number of museums that have been focusing on how you use digital tools like business analytics to maximise income on-site, by how you’re doing staffing or ticketing or pricing. This may not be applicable when you’re having to severely limit who can come to the museum. If they can come at all.”

In terms of meaningful digital investment, she says:

“One of the things TrendsWatch did, and it’s a complicated and difficult topic, is to tease out some of the diagnostic questions museums can ask themselves about what it’s worth investing in right now. At the moment, they have relatively little capital to play around with, and can’t take large risks.

“They need something that will help retain their audience, reach people in meaningful ways, and also build their income streams. Things that will still be critical parts of museum operations in the future, as they reopen and build.”

Challenging misinformation

“Another issue that we highlight in the report is remembering that museums are tremendously important drivers and protectors of equity. Particularly in times like this, when, so often, the most vulnerable are the people who take the biggest hits.”

In the US, vaccine hesitancy and misinformation is a significant factor in missing a portion of the population. Museums are doing really great work

An area, Merritt maintains, where museums are excelling, is in the provision of reliable information about vaccines. The AAM is also supporting the initiative, ‘Vaccines & US: Cultural Organizations for Community Health’. This brings museums, libraries and cultural institutions across the US together to support the national effort to provide Americans with accessible, trustworthy information.

“In the US, vaccine hesitancy and misinformation is a significant factor in missing a portion of the population. Museums are doing really great work.”

The need for digital literacy

Science misinformation is a global problem:

“There’s a need for more general digital literacy in helping people know how to get good information from bad. I have some hope, and this is not necessarily founded in data, that born-digital generations are going to grow up savvy about how to tell internet fluff from internet fact.

“Part of the problem is the algorithms the various social media platforms make money on. These give people more of what they want to consume. It’s like encouraging people to eat addictive snacks and candy. It’s not necessarily good for them.”

“A major driver of misinformation and some of the political conspiracy theories in the US is YouTube algorithms. They are recommending videos based on what you’ve already watched. In fact, no: you should not watch more videos on this. You should watch something else.

“I don’t want to against our previous conversation on ageism. I think it would help to have more data on the profiles of people who need different means of distinguishing online information. It may need to be tailored to a lot of things, including age, in terms of expectations and experience, in how people approach online content with scepticism or maybe unjustified faith.”

Museums & COVID-19

One of the feel-good stories of the year, according to Merritt, has been the way museums have stepped up and shown that they are part of the essential infrastructure of their community.

“They are doing important things like providing respite and relief, helping people to de-stress and raise their spirits with outdoor art installations. For example, museums have commissioned and placed art in front of nursing homes and hospitals. This is a way of providing art as a mental relief during COVID.”

“And that’s great. Other museums have also done outdoor installations helping collect histories of the pandemic. This is all central to their operations. In addition, museums have also thought creatively about how to deploy their resources to help whoever needs to be helped. We have museums using their grounds to raise food and give it to food banks, for example.”

Twenty public gardens across the country received funding to grow produce. This was part of the Urban Agriculture Resilience Program initiative.

Museums & the power for a bright future

Outlining another practical initiative, Merritt says:

“One of the issues for children is the fact in-person learning is so important. But how can schools with limited resources and space provide safe, physically distanced learning?

“The Louisiana Children’s Museum in New Orleans reached out to a neighbouring charter school, which serves primarily black, low-income children. They said, ‘Hey, you need more space. We are not open anyway; you can use the museum grounds and run your classes here.’ It was fabulous.”

As she says in her introduction to Trendswatch 2021:

“When the news flooding your feeds becomes too oppressive, take a break and disconnect from the present. Tell yourself some stories about how the future could be better. And remember you have the power to help those stories come true. You’ve got this, museum people.”