The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) is the second-oldest museum in Australia, its origins dating back to the mid-19th century.

It is home to nearly 800, 000 objects as diverse as fossils and fine art which make up the State Collections of Tasmania.

Janet Carding, Director of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, spoke to Blooloop about her career, her new role, projects of particular significance, and the impact of technology on a modern museum.

Carding’s first role in museums came about when she graduated from Cambridge University, where she had studied first sciences, and then the history and philosophy of science.

The Science Museum

After graduation she saw an advertisement for a junior curatorial role at the Science Museum in South Kensington in London, applied for the job and was accepted, beginning her museum career.

“I can’t say it was … a longstanding ambition. It was more that if you’ve got a degree in the history and philosophy of science and a job comes up at the major national museum that looks at the history of science, then that’s a match made in heaven.”

She worked at the Science Museum in a variety of different roles: as a curator; in programmes; exploring educational programmes – one of which was Science Nights, a sleepover learning experience at the Science Museum.

Then, in the mid 1990s, she became one of the leading members of the project team that developed the Wellcome Wing, an extension of the Science Museum which opened after five years in the year 2000.

“That was a major opportunity for me, ” she says.

Next, she did a brief exchange to the Museum of Science in Boston, before returning to work at a more strategic level.

“We did a review of the whole organisation in terms of strategy, and also the sister organisations, the National Railway Museum and the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television, which is now the National Media Museum in Bradford.”

By this point she was a member of the senior management team for all three museums, and felt she needed to broaden her experience if she was to continue in museums, something she was now determined to do.

The Australian Museum

In 2004, looking to move to another city where there were internationally significant collections and an opportunity to do something different, she came to Sydney.

The Australian Museum in Sydney turned out to be a great opportunity. She spent six years there.

“Once again, we built an extension to the museum; we built several new galleries, and we redisplayed much of the museum and put together a master-plan for its ongoing revitalisation. My job there was the Assistant Director of Public Programmes and Operations, and so covered the full suite from exhibitions, programmes, web and online activity, but also through to the business side of the museum, so finance, HR facilities, information technology and so forth. That was a great job.”

First female director of the ROM

In 2010, she was approached about the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, was successful in the recruitment process, and moved to Toronto for four years.

It was her first leadership role in museums, and she was the first woman to be Director of the ROM.

“If the Science Museum was mainly science and medicine and anthropology and technology, and the Australian museum was a mix of natural history, indigenous cultures and world cultures; then the Royal Ontario Museum has the whole lot – it is an encyclopaedic museum with everything from art, to science to history, so that was an interesting next step for me.”

It was also an opportunity to learn more about something in which she was particularly interested, at this point: the North American context, particularly around fundraising, development, and philanthropy.

Having been in Canada for four years, Carding wanted to return to Australia. She felt she had done as much as she could in terms of the Royal Ontario Museum, and the opportunity arose to be Director of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. She went through the recruitment process, and joined the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery as its Director. She has now been in Hobart for six months.

The place where all of the key Tasmanian stories are told

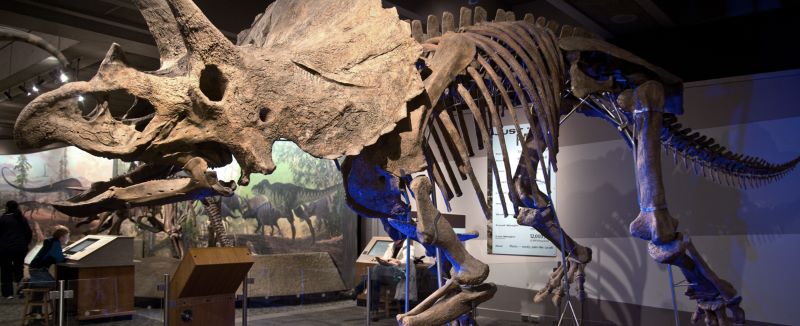

The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery has a substantial collection both in natural history and in history, in indigenous cultures and in art.

“This is a place where all of the key Tasmanian stories are told –about the unique animals and plants that live here; about the history, both the very substantial indigenous history of Tasmania, which, because this is an island which has been separated from the mainland for probably at least 10, 000 years, is significantly different from that of mainland Australia.”

There is also the story of the European settlement: the story of the convicts. Carding points out that this is perhaps the place in Australia where the convict story is most visible, both in the landscape, and in the architecture.

The way that the colony grew up in the nineteenth century fed through into art, history and culture. All of these things are detailed in the museum’s collection.

“We are an active, collecting institution. We have scientists working on both animals and plants: we have the State Herbarium here, as well as a very strong collection of thylacine, the famous endemic Tasmanian tiger, which became extinct in the 1930s. (The last known thylacine died in Hobart Zoo in 1936, but the species was not officially declared extinct until 1986.)

We have a great collection of colonial art; we’re actively collecting contemporary Tasmanian art as well. It’s a fantastic combination of things.”

A sample of recent and current exhibitions gives an idea of the museum’s diversity.

“We had a survey exhibition of Patrick Hall’s work on display. Hall is one of Tasmania’s leading artists who produces works of art that are shaped like furniture. At the time [a month into her tenure] we had just opened an exhibition on WWI, and we’re planning an exhibition that will look at the expedition that Napoleon sent to the southern oceans 200 years ago, where they made contact with the indigenous people here in Tasmania, and recorded that interaction. It gives you a sense of the variety of the things that we’re undertaking here.”

This exhibition is a collaboration between the Museum of Natural History in Le Havre, France and six institutions around Australia, including TMAG.

Carding has no immediate ambitions to impose her vision on the museum: clearly, she would prefer to learn about the community it is a part of, identify its strengths and any lacunae in the collections, and think about what it might need over time.

“This museum has just been through a redevelopment and we have the great opportunity that we sit in the middle of the waterfront in Hobart, and Hobart is, like the rest of Tasmania, becoming a bigger tourist destination each year both for people from other parts of Australia, but also internationally. What I want to be able to do is to make sure this museum is a must-see destination for tourists coming to Tasmania. But also I think there’s another incredible opportunity here. There’s a very strong sense, with the island culture, of Tasmania having its own identity, and so there’s a great opportunity to build the involvement of the local community with this collection.

“I’d like us to be on the must-visit list for locals and for tourists.”

A Strong Sense of Community

Nina Simon spoke recently about how small museums have the potential to be part of what she calls ‘the participatory revolution’, because they are so engaged in their communities. Carding agrees: one of the topics she has spoken on at conferences is on a similar theme.

“You would think it would be the large museums with their high level of resources that would be the innovators, but often they’re very locked into particular ways of working and it’s harder to experiment or take risks, while the smaller organisations that are much more in tune with their communities can potentially be the ones that are reinventing the idea of museum. That’s something that I think we need to explore here in Hobart.”

With smaller museums it is possible to engage and forge a relationship with every visitor, particularly if they are local, something that is impossible for the large, big name institutions.

“Tasmania is a great place for people having a sense of knowing each other, and it makes for this very strong sense of community. The museum’s role can be to help making those connections within communities, but also to make those connections between different communities. I know that’s something that’s part of the work Nina Simon is doing in Santa Cruz, and I’m interested to see what that would mean in a place like Tasmania, where there is a very strong sense of community being intertwined.”

It is Carding’s contention, having worked in museums and galleries that have different collecting focuses, that though it is very easy for museums to become very specifically focused on their own discipline and their own area. While museums are a sector with substantial expertise – like professional consultative bodies such as universities and hospitals – at the same time it is essential for museums to be highly networked into their communities:

“…particularly because we have a public face. I think that does mean that we have to think in a slightly different way. We have a large research component, so how do our visitors experience that? How do our visitors know what’s going on behind the scenes?

“I think in the past museums used to present themselves to the world as rather timeless, static places, and there’d be a frenzy of activity going on behind the scenes. I think that what we’re starting to see, and what I’m much more interested in, is how we share with our visitors that we’re a work in progress, that there are new ideas and new thinking. That the museum is a place full of people as well as collections, and that you can have a relationship with those people, and interact with them.”

Memorable Projects

Carding’s selection of particularly memorable projects from her career so far showcases the eclecticism of the museum world.

“I have to say the Wellcome Wing was a fantastic experience: to have the opportunity to be able to build a purpose-built museum wing, and then to be able to create the inaugural exhibitions. It’s now fifteen years old; I went back and had a look at it recently, and it’s amazing what has stood the test of time. At the same time, as we anticipated, the content has all changed. And, so that was something of which I feel very proud.

“In terms of other achievements, sometimes it has just been a privilege to be part of experiences, and I remember, soon after I arrived in Australia, being able to be part of a ceremony for the repatriation of human remains of indigenous people that were being returned from overseas.

“And that was something that, as somebody active in the museum world – I’d been to conferences, I’d heard papers about this, I’d heard arguments and discussion about the ethics, and what should be done – but actually to be part of seeing a community receive human remains back onto their land and deal with all of that was a very moving experience. It really showed me the significance of the work that’s going on in museums, particularly in Australia and other parts of the world around indigenous issues. That was a very important moment.

“I can name others. Being part of the day that the Royal Ontario Museum was a hundred years old was a very special moment as well. The Lt. Governor read out a touching message from Queen Elizabeth II, and that same evening we held a party where we’d invited every member of staff who’d ever worked at the ROM, and everyone who’d ever volunteered at the ROM, to celebrate our centennial.

A Museum in Perpetual Beta

Speaking about the function of a modern museum and the way technology impacts on that, Carding contends that the function of a museum is to create a destination, whether physical or virtual, where people can explore their own interests and learn more about themselves, and posits the notion of a perpetual beta museum.

“I think that technology is changing museums. We now have the opportunity, with technology, for people to be able to engage with the whole of our collections, rather than with the part that’s on display at any one time – and I mentioned before that museums used to be quite static places. My sense has been for a while that, in a world where nobody expects Google or Wikipedia to be finished, and where Apple releases a new version of its software a couple of times a year, in those circumstances people are now used to the idea that what you’re seeing is a work in progress, that things aren’t finished.

“I think that the sense of museums as more dynamic, unfinished works-in-progress is also now expected, and that means that we need to be spending more time working out how we actively involve our communities in what we do, and for them to be able to see that difference. Because, I think the down-side is that if we remain static, we’re going to be less interesting in a world where other things are being updated in real-time. Hence a museum in perpetual beta.”

She concludes by describing what she would like her legacy to be:

“When you work in organisations like this one – the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery was was established in 1863 – so it’s been here a lot longer than I have and will be here long after I’m gone – you start to realise that everybody’s just a small part of the history of the organisation.

“But you always want to leave an organisation stronger, and for me part of that legacy is that I’d like us to think differently about the skills that we will need to work in museums. I’d love to think that the way that we plan, the way that we work together, the kinds of skills that we focus on, the way that we talk with our visitors about what we do, that I might have been able to influence that a little.”

Images: Science Museum, Museum of Science Boston, TMAG.