Oceans (or Oceani in its Italian debut) is the latest travelling exhibition from the National Geographic Society, showcasing the work of legendary underwater photographer David Doubilet.

It is currently on show in Florence, overlooking the historic city from the terraces of the Villa Bardini.

Running until April 2026, the exhibition is more than just a collection of stunning images — it is a blend of storytelling, conservation science and immersive experience design. It invites visitors to explore a world that feels both alien and intimately connected to our own.

To understand the creation, curation, and mission behind this project, we speak with Doubilet, the pioneer of the ‘over-under’ split-lens technique, and Cynthia Doumbia, senior director of business development at the National Geographic Society.

They show us how a collection of photographs from the past fifty years is used to promote empathy for the planet’s most vital resource, and how the exhibition sector is changing to meet the challenges of a changing world.

Inside a hidden world

David Doubilet is a renowned name in underwater photography. With over 70 feature stories for National Geographic, his work reflects the evolution of the medium and the decline of the marine environment.

For Doumbia, Doubilet’s extensive body of work made him the perfect subject for a major solo exhibition.

“Throughout his career as a contributing photographer to National Geographic magazine, David has spent more than 27,000 hours at sea and produced more than 70 feature stories,” she says.

“Creating a travelling exhibition based on his work gives the audience a peek into the hidden world he’s spent five decades documenting. In one show, visitors can see images from equatorial coral reefs to life beneath the polar ice.”

For Doubilet, however, the journey has been shaped not only by geography but also by a sequence of technological revolutions that have fundamentally changed how we see the ocean.

“I am learning that life is about revolutions: social, political, technical and countless more,” he says.

“Jacques Cousteau and engineer Emilie Gagnan invented a way to breathe underwater on demand in the decade I was born. I came to National Geographic fifty-five years ago during a technical photographic revolution that had an enormous impact on my career and everyone who followed.”

New tech, new possibilities

Doubilet recalls the era of film with a blend of nostalgia and pragmatism, commenting on the limitations that shaped the early days of underwater exploration.

“The revolution was led by photographer Bates Littlehales, who developed the Ocean Eye underwater camera housing for the Nikon F camera that would allow us to photograph underwater using a range of macro and wide-angle lenses,” he says.

“We could carry multiple housings with different lenses and capture a shrimp, shark or shipwreck…in 36 film frames that I would not see until I returned from the expedition. If there was a camera problem, I learned about it later…in the editor’s office.”

The transition to digital has been profound, enabling a level of precision and storytelling previously impossible.

“Fast forward to digital, countless frames — as many as you can take on a tank of air. Sensors that capture more and more information in a single pixel bring the sea to life. We used to struggle in unworkable lowlight, but now we adjust to higher ISOs we only dreamed about.

“The strobes we carry to light the corners of the sea or stop action are faster, using fibre optic and can synchronise remotely to illuminate a large reef. Now you can see the image, correct the composition, surface and send the image to the editor that day.

“Much of the guesswork is gone, but you still need to visualise the images and the story they will collectively tell.”

Curating opposites

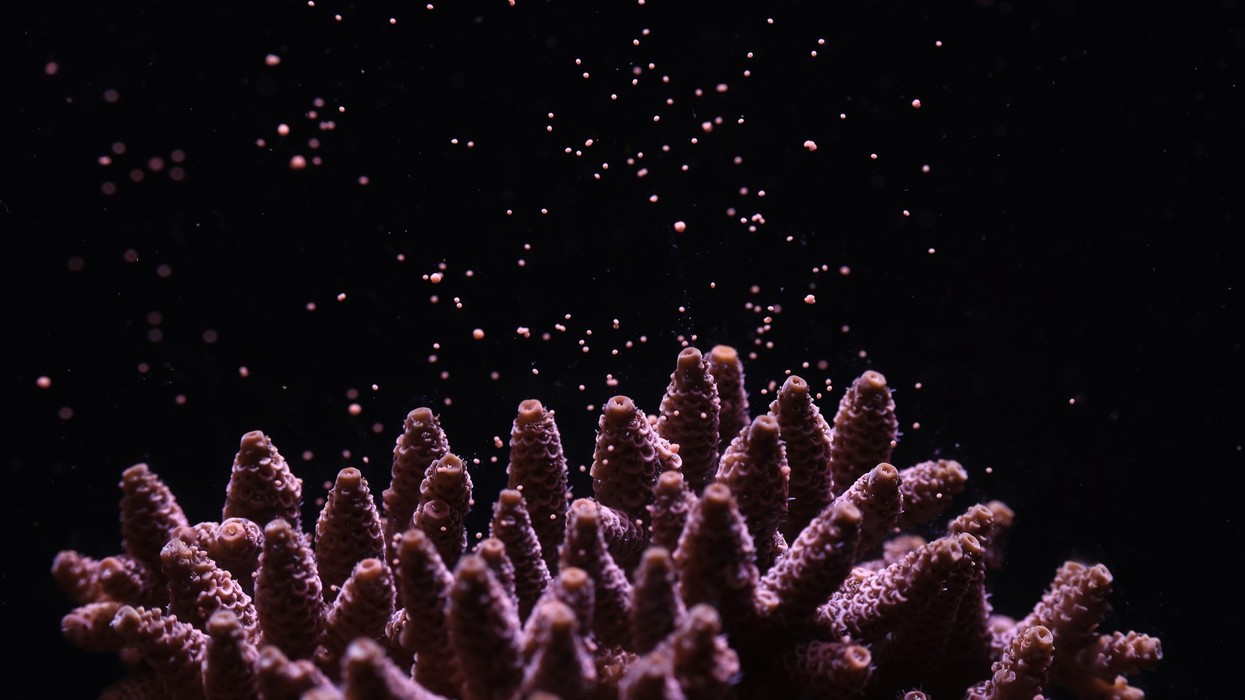

Oceans is not arranged in chronological order. Instead, it is curated around a unique narrative of opposites. This concept reflects the duality of the ocean — cold/warm, close/far, bright/dark — and echoes Doubilet’s distinctive photographic style.

According to Doumbia, this thematic approach allows the exhibition to sit at the crossroads of storytelling and science:

“During David Doubilet’s five-decade-long career at National Geographic, he has been witness to both the beauty and the devastation in our oceans,” she says.

“He is well known as a pioneer of the ‘over-under’ photography technique, which requires a bit of trial and error; he physically needs to position himself in a way that factors in lighting, perspective and angles to balance all these elements to achieve the perfect shot.

“The ‘opposites’ format is a narrative arc that plays on the need for balance in technique, storytelling and nature.”

Doubilet credits the genesis of this theme to the exhibition’s curator, Marco Cattaneo, editor of National Geographic Italy.

“I am grateful to Marco for exploring my archive of National Geographic stories across five decades and visualising how it might flow through the galleries, small rooms and hallways of the villa, which is art itself.

“He submerged into the body of work from equator to pole, warm to cold, night seas and sunlit reefs and emerged with the idea of opposites. The result is that the range of my photography came to life in a way I had not expected.”

The exhibition features over 80 photographs that illustrate this diversity. Visitors can see an aerial view of the Great Barrier Reef, taken from a De Havilland Beaver aircraft, juxtaposed with a close-up of a young green sea turtle swimming in Nengo Nengo Lagoon, French Polynesia.

The images range from the playful grin of a rainbow parrotfish in Queensland to the abstract beauty of corals at Tubbataha Reef National Park, highlighting the wide variety of marine life.

See also: One World, One Chance: immersive media inspires a movement for nature

The debut venue: Villa Bardini

The location of an exhibition plays a crucial role in the visitor experience. For Oceani, the debut venue, Villa Bardini in Florence, offers a poetic contrast to the underwater subject matter.

“What I love about touring exhibitions is that no two shows are the same,” says Doumbia. “The venue, the city and the audience make the exhibit take on a life of its own.

“We’re always discovering something new from venue to venue, which images are resonating, how much prior understanding of the subject matter does the audience have, how people are finding out about the exhibition and more.”

Doubilet adds that seeing his work in such a storied location was an emotional experience:

“I did not visualise that Oceans would come alive in the Villa Bardini overlooking the magnificence and beauty of Florence below its terraces and gardens. Exhibitions are often in minimalist, austere settings that let the art speak.

“Walking room by room through the exhibition in the Villa Bardini, I became aware of the gravity of time, detail, history and legacy resonating within the walls of the building and city below.”

The contrast between the ancient city and the timeless ocean created a unique atmosphere for reflection.

“When I was alone, slowly wandering through the galleries, I became mindful, perhaps, of what I have accomplished, but maybe more importantly, what I want to accomplish in the sea before I am to encounter the conclusion to my own story.”

Conservation awareness

At the heart of the National Geographic Society’s mission is the effort to illuminate and protect the wonder of our world. Exhibitions like Oceans aim to be more than entertainment — they also serve as tools for conservation awareness.

“Every day our Explorers work tirelessly to save and protect the beauty and wonder of our world,” says Doumbia. “Our travelling exhibitions are a platform for amplifying and bringing that sense of exploration to people in a way that is accessible as well as entertaining.”

The medium of the exhibition offers a tangible connection that digital screens often lack.

“It is often said that the first step in conservation is empathy,” says Doumbia. “Exhibitions help in building connections by immersing you into a topic in a way that perhaps other media cannot.

“In the ‘cute’ section, you see intimate portraits of bright and vibrant Nudibranch whose colourful bodies are a warning sign of their potential toxicity. Some nudibranch species face a significant threat of habitat loss [of coral reefs] due to pollution and coastal development.”

The exhibition does not shy away from the harsh realities of environmental degradation. One section offers a stark look at the effects of climate change.

“David and his partner Jennifer Hayes visited Tumon Bay, a popular dive site on the island of Guam, twice in 2005 and in 2017,” Doumbia says.

“They observed that what had been a flourishing coral reef just 20 years ago had been exposed to dramatic bleaching, leaving an expanse of debris on the seabed.”

Doom versus hope

Doubilet approaches this balance of beauty and devastation with the integrity of a journalist.

“Early in my career, much of the world thought that the oceans were infinite, but the truth began to reveal itself as human greed knew no limit and still does not,” says Doubilet.

“The truth is, the oceans are finite and fragile. As a journalist, we must confront the hard truths facing oceans today, a consequence of greed and our inability to be inconvenienced.”

However, he insists that doom must be balanced with hope to inspire action.

“There is an equal and perhaps more important need to balance the devastating truths with the resilience and conservation victories that are out there, and they are more than hope — they are happening,” he adds.

“We must report, but we must inspire hope, accountability and action. My goal is to connect people to 70% of their planet and to get them to care.

“How wonderful it would be to act instead of react.”

The power of trust

In an era where digital manipulation and AI are becoming ubiquitous, Doubilet believes that the role of the conservation photographer is changing.

“The pictures we take and share as journalists must stand on truth, or we have already eroded trust. Digital manipulation and artificial intelligence are upon us, creating doubt. There is doubt surrounding the media and reporting.

“As conservation photographers, we must be the guardians of truth to earn, keep and guard trust in storytelling.”

This commitment to authenticity is a hallmark of the National Geographic brand.

“There is a reason National Geographic magazine requires photographers to submit unmanipulated raw files. The National Geographic Society began in 1888, and it became the platform for the world and all that’s in it. So, highly regarded and trusted people would not throw the magazines away — they would cherish them.

“The power of trust is priceless.”

Measuring the success of Oceans

For the team at the National Geographic Society, the success of an exhibition is measured not only by ticket sales but also by changes in visitor attitudes.

“Impact can include learning, attitude and behaviour changes as well as engagement,” says Doumbia. “If a visitor can leave an exhibition having learned something, that is great — if the experience inspires our visitor to take informed action to protect the wonder of our world, that is even better.”

The exhibition clearly connects the imagery to worldwide conservation targets.

“Oftentimes on a text panel, we might suggest real-world action they can take to help save the planet.

"In Oceans, there’s a text panel which highlights the fact that the National Geographic Society has launched numerous research and documentation initiatives around the global 30X30 campaign to protect 30% of the oceans by 2030.”

She also cites interactive elements from other exhibitions as examples of how they drive engagement.

“Another example is the Tree of Hope interactive in our Becoming Jane exhibition. As visitors pledge to make changes to their lifestyles, their names are added as leaves to a tree that grows full and vibrant, showing that small acts can have a collective, big impact.

“If they choose to, visitors can also sign up to get more information from the National Geographic Society.”

Bringing Oceans to the world

Following its run in Florence, Oceans is set to begin a worldwide tour. The logistics of moving such a show demand careful planning and flexibility.

“From a technical standpoint, when working with international host venues, we provide the digital versions of the content so that they can print and produce locally,” says Doumbia.

“We also advise on the layout and floor plan to ensure that National Geographic’s quality and standards are adhered to.”

The format's flexibility suggests a long life for the exhibition.

“The exhibition will be available for hosting both domestically and internationally starting in April 2026. We look forward to speaking with venues worldwide interested in bringing this exhibition to their market.

“So far, the reception has been wonderful, and more than 6,000 people have seen it since it launched at Villa Bardini in Florence, Italy. This exhibition has been attracting a lot of young families with children.”

Looking ahead, Doumbia suggests that the National Geographic Society will continue to push the boundaries of how these stories are told.

“We will continue to bring visually stunning experiences in the years to come. Whether it be immersive, interactive or something in between, we strive to bring wonder and awe to our audience.”

Sparking conversation and change

Ultimately, the goal of Oceans is to remind us that humanity is not separate from the natural world. As the exhibition prepares to tour the world, Doubilet hopes visitors will take the time to genuinely connect with the images.

“The act of going anywhere requires interest, energy and the desire to learn. When someone walks through the gardens and comes through the door of Villa Bardini, they have made an investment of time — a most precious thing. They are there to expand,” he says.

“I hope they leave with an appreciation for the sea, our human connection to it, and inspiration to learn more about it and ultimately to invest more time in protecting 70% of our home.”

He remains passionate about the power of the shared image to spark conversation and change.

“I take great joy in making pictures, but I take greater joy in sharing them, watching and listening to the conversations they spark.

“I know it is a cliché, but now more than ever we need to understand that we are connected to this planet — a part of it, not above it or separate from it.

“The oceans are the engine of our planet — they are an oceanic prairie that feeds billions of people, and we need first to recognise that, respect that and act upon that to protect these already wounded resources for generations to come.

“Pictures have the power to educate, celebrate, honour and humiliate, and they have the power to inspire. This exhibition is a portal through the largest border on our planet, the surface of the sea.

“If one single picture inspires a single human to connect, we have made a difference.”

Oceans is currently open at Villa Bardini in Florence until 12 April 2026 and will then be available for international touring.

Charlotte Coates is blooloop's editor. She is from Brighton, UK and previously worked as a librarian. She has a strong interest in arts, culture and information and graduated from the University of Sussex with a degree in English Literature. Charlotte can usually be found either with her head in a book or planning her next travel adventure.