The White Cube project uses art and architecture to connect people on an abandoned Unilever plantation in the Democratic Republic of Congo with Western museums and the art community that has profited from the region's commercial and cultural exploitation. Its goal is to redirect funds to help residents reacquire and revitalise their land.

The project presents a groundbreaking framework for institutions to move beyond mere symbolic gestures of decolonisation and generate a meaningful impact for the future.

Further iterations are planned, including one in the Netherlands. There is huge potential in adapting this methodology to work with various underrepresented communities that have been exploited and abandoned by industry, enabling them to reconnect with their cultural identity and become self-sustaining.

David Gianotten, managing partner and architect at OMA, speaks to blooloop about the project, exploring how the approach emphasises community engagement, local materials, and sustainable practices, highlighting the importance of listening and adapting to community needs.

We’re looking at how this model can work elsewhere, in other communities that feel left behind or unrepresented in high culture. It’s about sparking debate ... not just about raising funds for elite art scenes, but empowering people to reclaim and express their cultural identity.

The power of architecture

Gianotten oversees OMA’s organisational and financial management, business strategy, and global growth, alongside leading his architectural portfolio.

He leads major global projects, including the Museo Egizio 2024 in Turin, the Selman Stërmasi Stadium transformation in Tirana, Albania, the Waterkant masterplan in Rotterdam-Zuid, and Amsterdam’s Bajes Kwartier, which converts a 1960s prison into 1,350 apartments.

Other projects include Eindhoven’s VDMA, which is transforming an industrial site into a mixed-use hub; the new Koepel District in Breda, converting a Panopticon into a mixed-use area; the Innovation Partnership Schools in Amsterdam; and the Metropolitan Village, a high-rise residential building in Taipei.

Gianotten’s projects have garnered recognition, including the NRC’s Best Architecture of 2024, Architectural Digest’s Great Design Awards (2020), and the Australian Institute of Architects Western Australian Chapter Awards (2021). He lectures globally on topics such as the concept of circular design, the future of the architectural profession, the role of context in projects, and speed and risk in architecture.

The idea behind White Cube

The White Cube is a project initiated by the Dutch filmmaker and digital artist Renzo Martens. His work explores the impact of companies with colonial histories, particularly those that sponsor the art world, on the places they once exploited.

“In this case, the focus was on Congo, where Unilever had left behind a plantation that was no longer in use,” says Gianotten. “The local people, who had worked there, were left without jobs or prospects. They were stuck with a palm oil plantation that didn’t support the original ecosystem and offered no real future.”

The idea was to buy back the plantation and give the local community the tools to be creative—to create their art, print it in chocolate, and exhibit these chocolate sculptures in Western museums, often sponsored by the same companies involved in colonial exploitation.

“The money raised through these exhibitions could then be used to buy more land, build a museum as well as a debate centre, and create a space for these artists to discuss both their history and their future.

“It was also about restoring biodiversity to the land.”

When the idea gained traction, Martens invited OMA to join, to help design the White Cube itself, along with housing for the local community and guest facilities.

From the violence of the plantation system to the aesthetics of the white cube, the film puts forward a proof of concept: museums can become decolonized and inclusive, but only on the condition that the benefits accrued around the museum flow back to the plantation workers whose labor financed – and in some cases continues to finance – the very foundations of these institutions.

“There was a meeting with Unilever, who weren’t enthusiastic, but eventually had to give in because the project gained traction. The locals began producing their art, sometimes reflecting the harsh conditions of the past, but also hopeful visions for the future.”

These clay artworks were scanned, transformed into chocolate sculptures, and exhibited in galleries in cities such as London, New York, and Amsterdam. Sales from these pieces generated funds to build the White Cube, additional facilities, buy more land, and restore the local ecosystem.

From Congo to the world

Martens filmed the entire process, from Congo to the international exhibitions, which became the film White Cube. As the project gained more attention, it sparked debate about African art held in Western museums, often seen as sacred by local communities but treated as artefacts or even stored away in the West.

“The question became: can we bring them back, so they can be displayed in Congo, where they belong? That part was harder than the chocolate sculptures. But eventually, some Western museums began loaning pieces back to the White Cube.

Local communities shouldn’t just supply culture for global consumption. They should be empowered to represent their own creativity and have a voice in the art world.

“The whole project gained momentum. We even made the front page of The New York Times, not just the culture section. It led to broader recognition that local communities shouldn’t just supply culture for global consumption. They should be empowered to represent their own creativity and have a voice in the art world.”

The White Cube in Lusanga became part of the Venice Biennale, tying Congo directly into the global art conversation.

“And now we’re looking at how this model can work elsewhere, in other communities that feel left behind or unrepresented in high culture. It’s about sparking debate, not just on colonial history, but on future possibilities as well. Not just about raising funds for elite art scenes, but empowering people to reclaim and express their cultural identity.”

Creating White Cube: a sustainable approach

Speaking about OMA’s approach to the site design, Gianotten says:

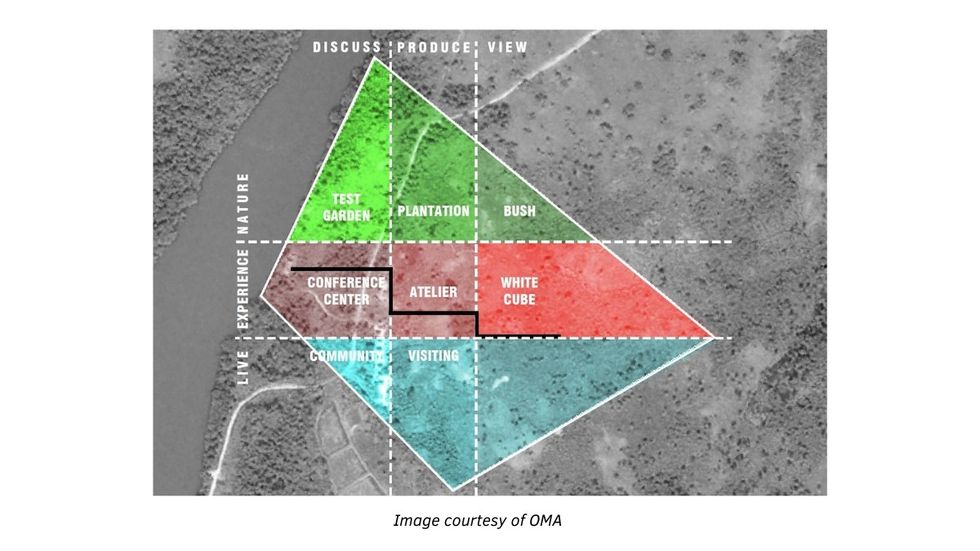

“We started by using the outline of the original palm oil plantation... One of the first things we did was rebuild a bridge that had been broken. Then we created a small village so people could live there."

“After that, we moved toward the waterfront. The first major structure we built was the debate centre so that conversations could begin. Next, we placed the atelier closer to the centre of the site. Finally, the White Cube itself was positioned right at the centre. These were the first four steps: creating a place to live, a place to talk, a place to be creative, and a place to display and connect.”

Beyond that, the team created another layer, a nursery with plants. They also preserved a part of the old plantation to show what it had been.

“Around the White Cube, we started replanting to bring back biodiversity, to show what the land could be again. The goal was to let people experience the richness of Congo and to reconnect with the land once more.”

In terms of materials, he adds:

“In areas like this, there’s very little available compared to the West, where we often work with modern or recycled materials. For example, we have a big project in Bali that’s made entirely from recycled materials. Here, we used only locally sourced materials. Many of which were taken from old storage buildings or structures left behind when the plantation was abandoned.

“We reused those materials to build the houses, make roofs, and even construct the foundation of the White Cube.”

Listening was key

The Cercle d'Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC), art collective was created during the project.

“Some of its members were already part of our initial group, but the collective took shape as the project developed. You can see that process in the film. It’s now an empowered group with an international presence."

When the team first arrived, the local community assumed they were just the next wave of colonisers coming to benefit from their land again.

“There was a lot of hesitation. There’s a scene in the film where Renzo, with his long hair and hat, looked so much like the colonisers of the past that they thought he had come back. But from the beginning, we engaged in real conversation.”

Watch White Cube from Renzo Martens

hereThe team didn’t come with a plan to impose, he adds:

“We didn’t implement anything until they were fully on board. Not because we pitched them a design, but because we asked, ‘What do you need?’

"That changed the tone completely. They saw we weren’t just there to listen; we were there to act. And we weren’t there to hand out money; we were there to help improve the situation. That’s when it clicked for them.

“From that moment on, they began creating art, drawn from memory, from difficult pasts, but also from beautiful dreams for the future. They realised we were genuinely there to empower them. The conversations became more content-driven. Many ideas emerged, and our role became helping to shape them into something feasible.”

Community buy-in

The White Cube project's shape emerged through dialogue and community buy-in. “That’s when we began designing and building, together with them and with local builders. We deliberately chose local people, not aiming for the best architectural outcome, but for the greatest local impact. We wanted them to learn, to build, to grow."

“That’s how we gained their trust. They never saw us as people trying to take something for ourselves, because every part of the project went directly to them: into their housing, their land, their exhibitions, even sending them to visit shows and learn how Western museums work.

“Everything we did was for them. The only thing we took was to make a film about it. And I think that made all the difference.”

They never saw us as people trying to take something for ourselves, because every part of the project went directly to them: into their housing, their land, their exhibitions

An authentic voice

Reflecting on the project’s initial aims and how these evolved, Gianotten says that, in the beginning, the project started as a criticism of the art world and its sponsors – “How big companies extract vast amounts of money and resources from faraway places and then, without hesitation, abandon those places, leaving behind a destroyed environment.

"Meanwhile, they use the money they make to sponsor art that’s only for the happy few, without channelling anything back to the communities affected.”

What Martens attempted to do was reverse that dynamic. The goal was to have the local people produce genuinely exciting art and ensure they benefited from their own creativity.

“We also wanted to start a debate around these culturally rich areas, showing that they have a lot to say, beyond the exclusive, money-driven art world. There’s an authentic voice and thought there, and that debate was important to us.

“Strangely enough, our exhibition was sponsored by exactly those kinds of companies, though they didn’t fully understand the story; they just wanted to be involved. That was unexpected. We thought we might end up with a small exhibition somewhere. But instead, we ended up in prominent museums and attracted a lot of attention.

“We didn’t have a clear goal beyond creating local impact and starting a conversation about how the art world is financed. We never imagined it would become more than a critical film. But in the end, it delivered a whole institution, an artist collective, and beautiful art.

“The debate about returning art pieces to Congo was never the aim at first. That emerged along the way, as the project gained traction, and we tried to use that opportunity.”

Key lessons from the White Cube project

In terms of the key lessons that the team took away from the White Cube project, Gianotten says:

“I think when you try to approach something, it’s easy to shout, but very difficult to listen—especially when you believe there is criticism involved. The challenge is how to solidify that criticism without stepping on toes. For us, it was really about showing that if you approach things from a different angle, you can empower a society."

"You can begin to change some of the negative circumstances, while everyone still embraces it, and it still holds a place in the art world."

“In the end, we felt we had to do something positive about something we were very critical of, to show that it’s possible to do things differently. That was the biggest learning. When you have an idea and you’re willing to shape it with the input of the people it concerns, great things can happen, sometimes unexpectedly.

“We started White Cube with a small grant Renzo won from a previous art project, and in the end, it became a whole organisation with many people in management working to keep it going. That’s an amazing achievement.

“So, don’t just aim high. Start a debate and see where it leads you.”

"Be genuine and real"

When asked what people should think about if they are looking to create a similar model, Gianotten says:

“The most important consideration is to be genuine and real. We understand that institutions and their funding often can’t fully separate themselves from their own goals. In this case, you need to be 100% flexible because you don’t know exactly what people want or need, or where it will lead."

![Cercle d'Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise - CATPC: Atelier de sculpture pour les femmes de Lusanga [Facebook]](https://blooloop.com/media-library/cercle-d-art-des-travailleurs-de-plantation-congolaise-catpc-atelier-de-sculpture-pour-les-femmes-de-lusanga-facebook.jpg?id=61222331&width=980)

“That’s very difficult for projects funded by institutions, which usually have a fixed goal or a rigid process. Those frameworks aren’t helpful here. You need a blank slate to truly accommodate the real needs that emerge."

“For us, that was the biggest learning. In the beginning, we thought, ‘Maybe we should do this, maybe that,’ but it turned out very differently because people had very different ideas. You have to be open to those ideas. If you follow that trail, people show incredible strength and creativity; even if they feel suppressed or hopeless about the future, they can blossom.

“That’s when you bring your expertise to help make that blossom a beautiful flower.”

It is, he says, about listening with an open ear and acting based on what people indicate, not coming in with a fixed name or plan. “If you have a plan before starting a project like this, don’t use it, because that plan will never become a reality.

“You need to start with an idea, but no plan.”

I've never been to school, I can't read or write, but thanks to these workshops, I've discovered that I can draw, convey a message through art, sculpture and performance.

Insights from greenloop 2025

This conversation was included in greenloop 2025, blooloop’s annual online conference for sustainability in visitor attractions, which took place online, on 13-14 May 2025. greenloop informs and inspires with top speakers, cutting-edge science, and practical insights. The event is available to watch on demand. (Attendees, you can view for free – watch out for the code in your email or contact events@blooloop.com)

Catch up on greenloop 2025

hereCharlotte Coates is blooloop's editor. She is from Brighton, UK and previously worked as a librarian. She has a strong interest in arts, culture and information and graduated from the University of Sussex with a degree in English Literature. Charlotte can usually be found either with her head in a book or planning her next travel adventure.

Dippy the dinosaur arrives in Coventry for new residency blooloop.com

Dippy the dinosaur arrives in Coventry for new residency blooloop.com

Erik Neergaard

Erik Neergaard Phil Hettema

Phil Hettema