To step into Sir John Soane’s Museum in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London, is to enter a space that feels less like a public institution and more like a portal into one man’s singular, obsessive imagination. It is a "dense collection in a small footprint", a labyrinth of light, mirrors, and antiquity that plays out like a lucid dream.

For Will Gompertz, who took over as Deborah Loeb Brice Director in January 2024, the museum is nothing short of "perfect".

Gompertz says the building is not merely a house, but a Gesamtkunstwerk, a "total work of art" where the architecture, the collection, and the light effects are inextricably linked.

"Sir John Soane never really designed it as a house," Gompertz says. "He’d always designed it as a museum for his objects. And then he figured out a way of living in it. So, it’s a museum designed to live in as opposed to a house museum".

"Soane designed his Museum as an Academy of the Arts," Gompertz says.

"He had this belief that if you want to appreciate one art form, you have to understand and appreciate them all. And so, there's this configuration of objects and artworks where you have all the different art forms speaking to each other".

It is this unique atmosphere, intended to evoke mood and atmosphere, that Gompertz is now charged with preserving and protecting into the future.

From the knife-thrower to the abstract: an outsider’s path

Will Gompertz is not a typical museum director. Born in Kent in 1965, the son of a general practitioner, he was expelled from school at sixteen and left with no A-levels.

This departure from the academic route seems almost hereditary: Gompertz’s early Victorian ancestors—Benjamin, Isaac, and Lewis Gompertz—were also outsiders to the establishment.

Being Jewish, they were barred from a university education. Yet, they thrived: Benjamin became a brilliant mathematician who invented the Gompertz Curve, Isaac became a poet, and Lewis was an animal rights activist and co-founder of what is now the RSPCA.

Gompertz’s own journey was equally non-linear. In a detail that speaks to his willingness to embrace the precarious and the performative, he once worked as a "knife-thrower’s stooge at a holiday camp on the Essex coast".

It was a visceral introduction to the world of entertainment; he says the sound of "heavy metal blades thudding into the board" against which he stood still haunts him to this day.

His professional epiphany regarding the visual arts did not occur in a lecture hall, but in a museum in Amsterdam during his early twenties.

He saw a painting by the abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning. The piece was titled Rosy-Fingered Dawn at Louse Point, a reference to a location in Springs, Long Island.

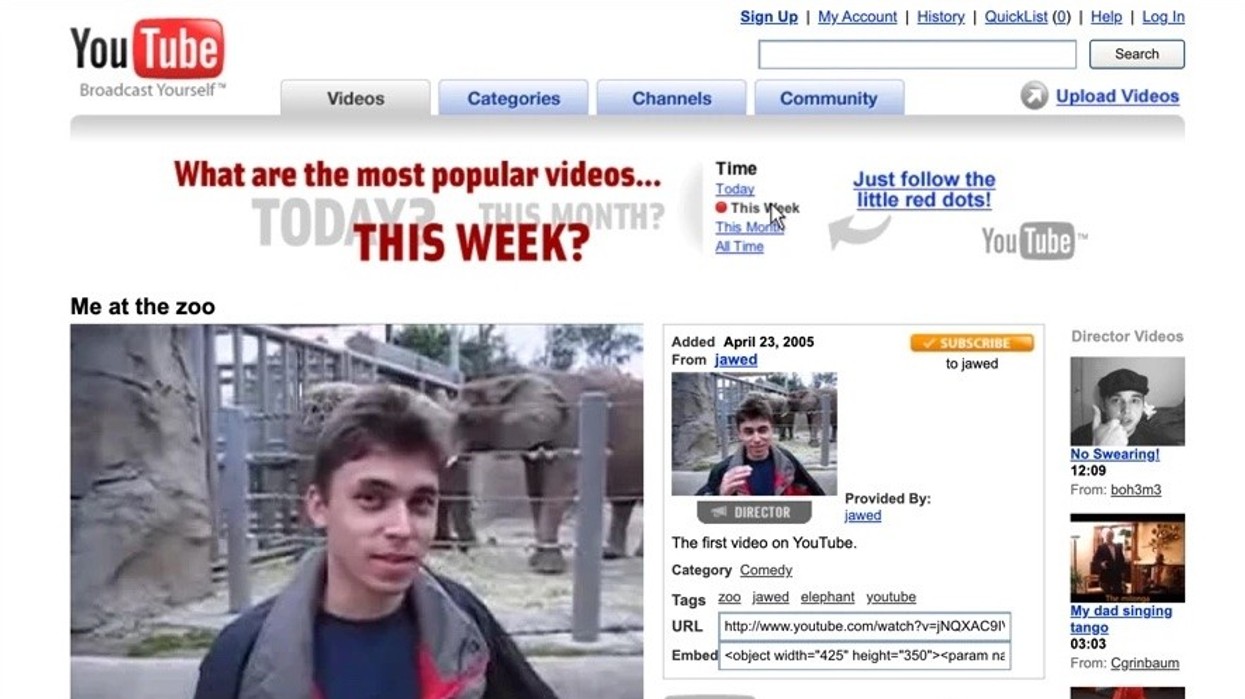

This is the painting that got me into art. Willem de Kooning’s ‘Rosy Fingered Dawn at Louse Point’ (1963). I loved it when I first saw it @Stedelijk all those years ago and I still love it today. A perfect picture for early spring. pic.twitter.com/Jus3stSUDE

— Will Gompertz (@Will_Gompertz) February 18, 2019

"I was just blown away," Gompertz says. "I didn’t realise you could do that with paint. It made a real connection. It’s like seeing an incredible movie or hearing a great piece of music".

He describes the painting as "thick and pasty," a work that seemed abstract but was "probably a sort of landscape". The experience was transformative.

The content business: Tate and the BBC

This accessible, visceral connection to art became a theme.

"The common thread throughout the whole of my career is to... build a bridge between art and the public," he says. This mission led him to the Tate, where he spent seven years helping to revolutionise the museum's relationship with the public.

There, he founded Tate Media, saying that the gallery was "fundamentally a content business and art is at its heart".

This perspective allowed the institution to own its intellectual property and animate its collection in a "myriad different ways," proving that a museum could operate like a media company without losing its soul.

His success at the Tate led to an eleven-year tenure as the BBC’s Arts Editor. He suggests that he was hired not for his journalistic pedigree—which he lacked—but perhaps because he fit the central casting image of an arts correspondent.

"I just looked like the arts editor in their mind; this arty bloke with long hair and dark glasses".

He says the BBC wanted someone from the art world who could be trained in journalism, rather than the other way around.

It was during this decade-long tenure that Gompertz developed a keen understanding of what the public actually wants from arts coverage. He realised the audience had little patience for the industry's bureaucratic side.

"People just weren't interested in funding stories," he says.

Instead, he found the audience had a genuine hunger for “hearing from brilliant people and having them articulate their ideas in a way which is engaging," he says.

This philosophy guided his work as he interviewed celebrated creatives, including Meryl Streep, Tom Hanks, and Paul McCartney.

The Barbican vs. the Soane: venue or collection?

After eleven years, the relentless unpredictability of daily news—where plans could be upended instantly by a breaking news story— led Gompertz to seek a change.

In 2021, he became the Barbican's artistic director. He says the experience was a "privilege," programming for Europe's largest arts centre across theatre, music, cinema, and galleries. However, the transition highlighted a fundamental difference between a performing arts venue and a museum.

"The Barbican is a venue," Gompertz says. "It relies on the constant generation of new programmes. It’s fantastic, but then it’s ‘right, what’s next?’"

Sir John Soane’s Museum offers a different kind of responsibility. "A museum has a collection," he says. "And that collection is rooted in an academic framework. They have this balance, this weight, this purpose".

The Soane is not about the continuing churn of the new, but about depth. "The Soane is in excellent condition... It’s been curated so brilliantly," he says.

The challenge now is "to increase knowledge, understanding, and appreciation of that collection, to scale the institution without losing its authentic, authored charm".

Expanding the "Academy of the Arts"

Gompertz says he is focused on fulfilling Sir John Soane’s original ambition: to create an "Academy of the Arts".

This presents a unique logistical challenge. The museum is a Grade I listed building with a finite footprint; it cannot physically expand to accommodate more visitors.

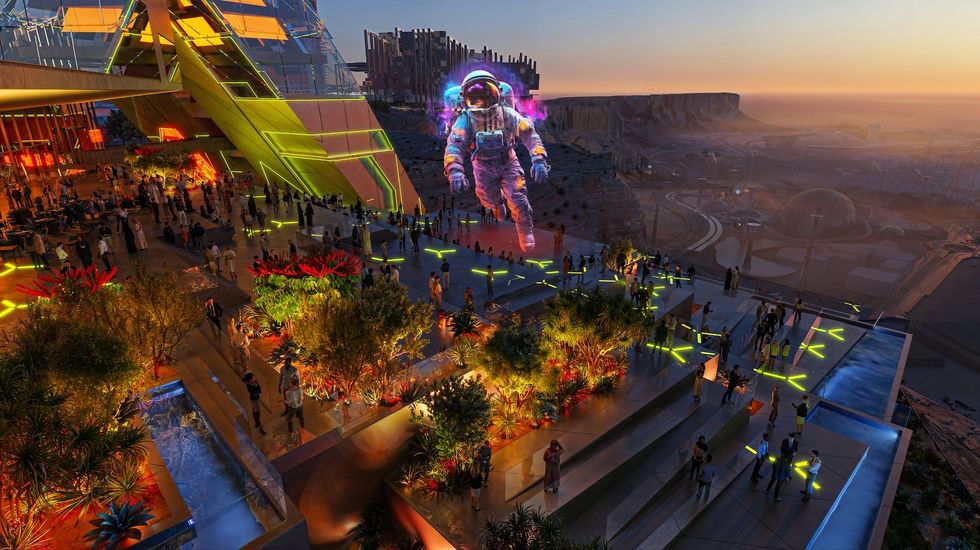

"We can't get more people in," Gompertz says. "It's fantastic, but in terms of fulfilling Soane’s ultimate ambition, which is to have an Academy of the Arts, that's something which I think we can do virtually".

"Soane's Portals to the Past": fulfilling the mission through Minecraft

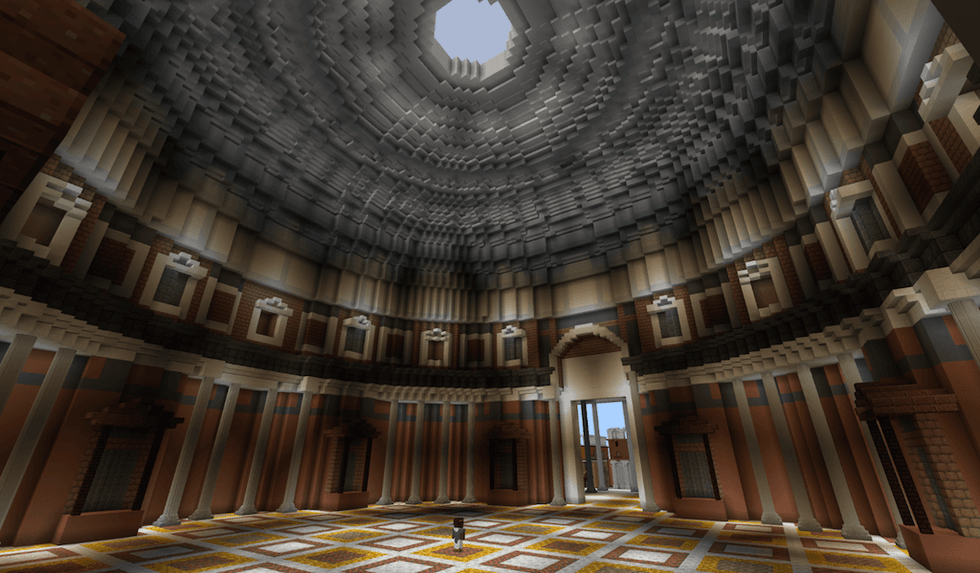

The most striking example of this virtual expansion is a project that bridges the 19th and 21st centuries: a collaboration with Minecraft Education.

Often described as 'digital LEGO,' Minecraft is a popular world-building platform where users use 3D blocks to create complex structures and environments. Launching on January 21st, this initiative marks the "first ever Minecraft world dedicated to creative thinking, architecture and design in the AI era".

The game lets young audiences study key artefacts in the Museum’s collection and design structures inspired by ancient civilisationsthat influenced Sir John Soane (1753-1837), including the Pantheon, the Temple of Zeus, and Seti I’s Hypostyle Hall.

After exploring limestone, granite, and sandstone columns, students return to London in Sir John Soane’s Model Room to build their own architectural legacy, inspired by the design practices learnt in the game.

For Gompertz, this is not merely a marketing project, but a direct fulfilment of Soane's educational mission. Since the physical "Academy" cannot hold more students, the digital realm provides the necessary scale.

"It’s called 'Soane's Portals to the Past'," Gompertz says.

"It takes you into classical antiquity, into ancient Rome, ancient Greece, ancient Egypt. You learn about the cultures, you learn about the aesthetics of their buildings. And then you come out, and you build your own legacy building within this same world".

Players will encounter virtual versions of Sir John Soane, his wife Eliza, and their dog, Fanny (though, he notes, the dog is "not called Fanny" in the game). He says the blocky aesthetic of Minecraft strangely complements the museum's architectural nature.

"It’s going to be available to schoolchildren across the world through the Microsoft Office 365 Education Licence," he says. "It exemplifies how technology can enhance creativity as opposed to suppress it".

By utilising this platform, Gompertz effectively transforms the museum from a local London treasure into a global classroom, realising the "Academy" concept on a scale Soane himself could never have imagined.

Architecture: the "pre-eminent art form”

This digital outreach sits alongside a granular educational strategy involving the Ark Academy chain. The museum is launching an enrichment class to reintroduce architecture into the curriculum. Gompertz argues that this specific focus is long overdue.

"In Soane's time, architecture was the pre-eminent art form," he says. "It's kind of slipped down the scale, but actually it's incredibly important, and it's something we can all have a say in".

The programme, starting with "Ark Soane" in Ealing, aims to teach children about the built environment and sustainability, leveraging the museum’s resources to show that buildings "speak of cultures... [and] of ambition".

The Drawing Office: where feathers created cities

While the digital strategy extends the museum outward, Gompertz is equally passionate about revitalising the museum's physical spaces, specifically the Drawing Office.

This "floating space," which hovers above the colonnade, was where Soane’s apprentices worked 12 hours a day, six days a week.

He describes the office as a "fantastic trick" of architecture. "It appears to float, but actually, when you look underneath, it's held up by the columns of the colonnade, but you would never know it," he says.

Closed to the public for 200 years and only recently restored, Gompertz calls it an "exquisite space". The walls are lined with plaster casts and fragments, acting as a "visual encyclopaedia" for students.

"When you go up there, you can see the materials that Soane used to design his buildings; he used a feather," he says.

"It’s just amazing to think that architects, until fairly recently... were using a feather to create cities. Isn’t that an amazing thought? Something as gentle and as ephemeral as a feather can create Pompeii or Rome".

To keep this history alive, the museum has partnered with the Jerwood Foundation to establish an artist-in-residence programme.

The residency is open to artists working with dry media (to protect the museum interiors and continue the tradition of the office as a place of active creation).

From immersion to AI

Gompertz’s plans for the Soane are informed by his views regarding the development of art and the role of technology. When asked about the rise of commercial immersive art experiences—such as the travelling Van Gogh exhibitions—he is receptive.

"The Soane is definitely an immersive experience. He [Soane] described it as trying to create a lumière mystérieuse. I am sure if Van Gogh were alive today, he would create immersive experiences.”

He cites the David Hockney experience at the Lightroom as a prime example of the medium done well. He says it felt "authored by him" and served as a "wonderful visual lecture". For Gompertz, the medium matters less than the execution: "Is it done with love and sincerity, or is it insincere?"

This connection between the Soane’s atmosphere and modern immersive experiences is not lost on contemporary filmmakers. Gompertz says that the museum acts as a magnet for directors: "Guillermo del Toro visited twice last year".

The townhouse featured in Yorgos Lanthimos’ Oscar-winning film, Poor Things (2023), was inspired by the museum. "Willem Dafoe's house is based on the staircase," Gompertz says.

According to production designers Shona Heath and James Price, they used the museum's "neo-classical skeleton" and its history as a "cabinet of curiosities" to forge the film's visual DNA.

So, what impact does Gompertz think artificial intelligence (AI) will have on art?

He does see potential in AI as a tool for conceptual art, where the "human bit is setting the parameters or the filters to provoke AI to come up with something that the artist has conceived".

Regarding the idea of AI actually creating art, he says that he has "yet to see a work of digital art that has touched me in quite the same way as paintings or sculptures or even performance or film".

The analogue soul of a digital future

Despite his enthusiasm for Minecraft and AI, Gompertz says he is adamant about preserving the museum’s analogue soul. The museum currently operates with almost no modern data capture—no ticketing system, no box office.

"The analogue thing does have a charm," he says. "By the time you’ve got into the museum, you’ve had good conversations with at least three members of the Soane team. That’s a pretty cool welcome".

Visitors do not seem to mind the lack of digital infrastructure.

Gompertz says that despite the absence of data, he estimates by eye that "at least a third of the audience are 30 or under," a demographic shift he attributes to the museum being an "absolute win on Instagram".

While he acknowledges that some digitalisation, such as a box-office system to manage queues, is likely "inevitable," he says he intends to maintain the personal touch.

This balance between the individual and the technological is central to his vision. He plans to overhaul the website to make the virtual experience "deep and rich"

Ultimately, Gompertz sees his role as facilitating a conversation across centuries. He compares visiting the Soane to a personal meeting with its creator.

"It’s two humans convening," he says. "The artist and the viewer.

"You’re conversing with the curator of this space, Sir John Soane, and what he’s trying to say. If you can create somewhere that makes people feel even more human, even more alive, even more curious, that’s spectacular. And that, I think, is what Soane delivers in spades".

In Will Gompertz, the Soane has found a unique director for a unique museum.

Under his stewardship, the "Academy of the Arts" is open for business and ready to welcome visitors whether they arrive through the front door at Lincoln’s Inn Fields or through a portal in Minecraft.