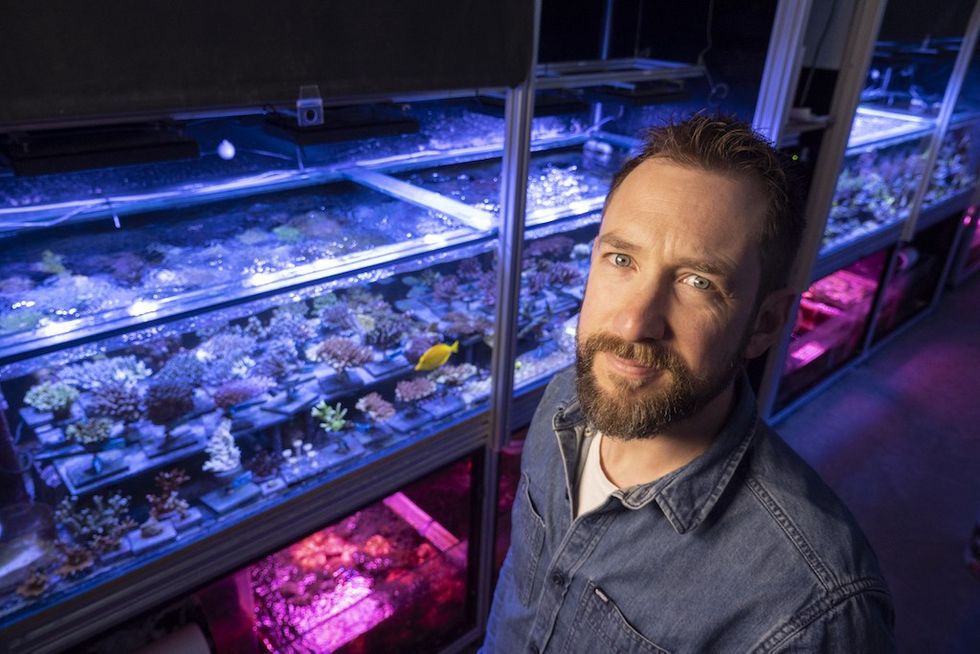

Dr Jamie Craggs, aquarium curator and living collections manager, has been at the Horniman Museum and Gardens since 2008. He is also a science associate at the Natural History Museum, London, and in 2016 was elected a fellow of the Linnean Society of London, the world’s oldest active biological society.

Previously, he was head aquarist at the London Aquarium, during which time he developed his interest in coral biology. In addition, he has spent time as an underwater cameraman in Borneo, filming and photographing the species on the coral reefs in the Celebes seas.

Project Coral

Craggs’ primary research interest is the reproductive biology of reef-building corals. In 2012 he founded Project Coral. This was a multi-year research project focused on developing techniques to induce broadcast coral spawning events predictably in closed-system aquariums.

He spoke to blooloop about this in 2016. Through developing a deeper understanding of broadcast spawning events in captivity Project Coral aimed to support climate change research focusing on reproduction and reef restoration efforts and develop new sustainable coral aquaculture techniques. In 2018 Craggs was named Aquarist of the Year by the Marine Aquarium Societies of North America.

“Project Coral has made huge strides in creating the protocols to induce coral spawning in lab conditions, and the Horniman’s research will continue to refine the techniques and understand the effects of climate change on coral reproduction,” Craggs said.

Craggs believes that a collection within a public aquarium should be used to deepen our understanding of biology and promote the conservation of species and habitats. Since arriving at the Horniman in 2008, he has developed various research collaborations with universities and aquariums and links with conservation organisations across the globe.

A lifelong passion

Blooloop caught up with Craggs again this year, and he spoke about his passion for coral.

“I've kept fish since I was about 10. I was a hobbyist fish keeper from a young age and had terrapins and goldfish and all sorts in tanks in my family kitchen as a kid.

“To start with, I had freshwater fish. Then had a bit of a break when I hit about 16, and then got back into it at university. I was breeding freshwater fish in the Halls of Residence at university. I sold those so I could get the equipment to build my first marine tank, back in 98. Keeping marine systems was viewed as a much harder thing than freshwater systems, in terms of technicality. It was that challenge that drew me to it.”

He got his first coral in around 1998:

“The system was pretty terrible. It was a soft coral, and it wasn't exactly thriving. That was my entry. I've grown up and lived on the coast all my life, and have been in or on the water since a very young age. So, I've always had a connection with the ocean.”

The importance of reefs

The planet’s coral reefs are currently facing existential threats from a combination of stressors. Perhaps the most significant of these is climate change.

“We know how important coral reefs are in terms of an ocean ecosystem,” Craggs says. “There are lots of figures thrown around. We know coral reefs cover 0.1% of the ocean floor. Yet between a quarter and a third of all species in the ocean either reside on the reefs or visit the reefs.

"Biologically, they're really important. They're incredibly diverse. From a human perspective, about 11% of the human population, half a billion people, rely on reef systems for the ecosystem services they provide.”

That might be as coastal protection, since the corals themselves are very efficient at diffusing wave energy and stopping coastal erosion. Or it might be as an income source from tourism, or as a protein source, from fishing:

“All these ecosystem services are incredibly important to half a billion people. The coral themselves build the structure of the reefs; they create that three-dimensional structure that allows this explosion of life to occur. If you lose the coral, you have a disproportionate loss of that biodiversity, which, ultimately, has knock-on effects on human wellbeing in communities that rely on them.”

Climate change causes challenges

Climate change is putting phenomenal pressure on the coral reefs.

“If some of the pressure on a damaged reef is removed, it can recover, but only if there's a reproductively fit population that is spawning and seeding that damaged reef and allowing it to recover. Understanding not just the health of the reef, but also its reproductive fitness allows you to understand how resilient it is, and how it can bounce back over time.

"Studying reproduction is fundamental if we are thinking about how these systems will repair or continue in the future. There are two groups of corals, or rather two predominant sexual reproductive modes than groups. One group are brooders, and they fertilise internally, producing fully formed planula larvae.

"These have spawned for many decades; nobody has had problems, certainly with specific individual species of brooders.”

The start of Project Coral

The second group is the broadcast corals:

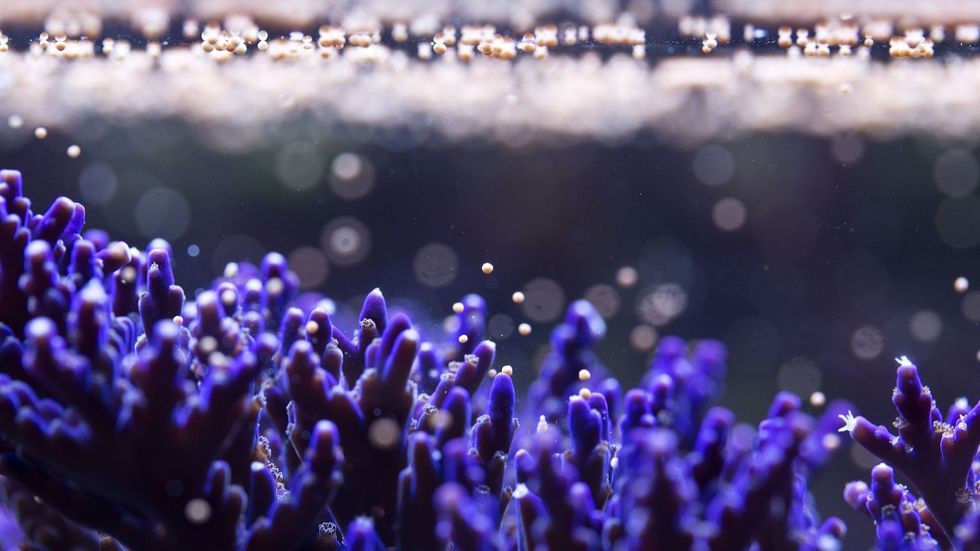

“The broadcast are the ones releasing eggs and sperm, where fertilization is happening in the water.

"Nobody had ever gone out and figured out how to predictably do that in an aquarium. There had been spawning events in public aquariums over the decades, but they had always been unplanned and unpredictable, often catching the onlooker by surprise. There was no awareness that it was actually going to happen. That’s really the spark that triggered me to start thinking about coral reproduction."

"In 2012, I said, ‘I want to do it. I want to be the first to go out and spawn corals; to break the code to it. Once you make it predictable, it opens up an absolutely colossal opportunity in terms of research into reproduction. That research can go in many different ways, but the platform of predictability is the thing that allows that explosion of research to take place.”

Initial success

In 2013, Craggs achieved his objective, discovering the combination of diverse factors – including water temperature, length of day, and phase of the moon - that triggered coral spawning:

“I started it all in 2012 by doing a lot of research,” he says. “One of the key pieces of information came when I was sitting at home in my kitchen going through Twitter, and I found a tweet from a Fijian dive company saying, ‘Come out with us in a few days and you'll see this coral spawning.’ I thought, ‘What? Hang on a minute. How do you know it's going to happen in a few days?’"

"That moment meant I could then start digging into all of those environmental factors and working backwards from that. That tweet was quite instrumental in looking at what I needed to do within an aquarium.

"By the end of January 2013, I'd managed to modify some systems that I already had here, and then I built two corals. I got lots of pieces of the same coral and the same species, and I stuck them on a rock to try and make a big colony quite quickly.”

Project Coral and a steep learning curve

Sure enough, it worked.

“One species spawned in September 2013, and then the following species spawned the following month. At the time, I was staying up all night long because I was treating it in the same mindset as going out and looking at it in the reef; I've been lucky enough to go out on a couple of expeditions to see coral spawnings in different places of the world."

"I had brought that thinking back from the field to the lab. I thought I needed the systems lit during the day and then spawning at night, as they normally would do.

"It meant I was absolutely knackered. I was doing 15 to 20-day stretches where I was getting home at about two, then having to be back here at eight in the morning to open the public aquarium. It was pretty full-on, but all part of the learning curve. You have to go through that pain to understand how you can do it differently."

New research

In lots of places around the world, coral spawning can be predicted fairly well, and more research is coming out. Australia, for instance, has been studied since the early to mid-eighties:

"A paper published in the mid-eighties is still the go-to Bible: it works; they figured it out back then. You can go to the Great Barrier Reef, use that paper, look at what's happening with the lunar cycle one year after another, and you can plan your whole trip around that. But obviously, to do that, you have to go out to Australia, and if you are in England, Sweden, America, or wherever, you don't have the Great Barrier Reef on your doorstep. That was really the catalyst."

"If more people could do this in Middle America or London or wherever that might be, it would mean more research opportunities, and might accelerate the answering of some of the questions.”

Project Coral is not a solution to climate change

When coral is under environmental stress from factors including temperature change, the algae-coral partnership becomes destabilised, and the coral expels the algae (or zooxanthellae) which provide the coral with energy from photosynthesis, leaving the coral ‘bleached’ and vulnerable. Coral bleaching is happening at a frightening rate.

“If we could sort out climate change, we wouldn't need to do any of this,” Craggs comments.

“Reef restoration is not a solution to beat climate change. It is about buying time so that these bigger issues can be sorted out, in whatever capacity that is. There is a lot of research exploring selective breeding and making stronger corals that can withstand some of the effects of climate change, and different groups around the world are working on this from many different angles.”

Some of the results of this research are encouraging. However:

“Fundamentally, we're not planting corals out at a scale that it is going to make a difference at the moment. There are lots of people trying to work out how that can be done at an ecologically relevant scale, though. We are inching forwards in terms of progress.”

Breeding super corals

Touching on some of the research being done, he adds:

“There’s a lot going on in Australia. There’s a lady called Professor Madeleine van Oppen, an ecological geneticist with an interest in microbial symbioses and climate change adaptation of reef corals at the Australia Institute of Marine Science. She started out with Dr Ruth Gates, who has, unfortunately, passed away. She was based in Hawaii.

"They had the idea of looking at selective breeding of what the press picked up on as ‘super corals’. Several groups have continued that work looking at the coral holobiont; both the coral and the algae that live inside the coral, Symbiodiniaceae. There are groups putting those algae, the Symbiodiniaceae, on what is effectively a thermal treadmill, heating them up and selectively breeding the cells that can handle the warmer temperatures."

"Part of that research is then to take those cells and put them inside the coral to see if it boosts the resilience of the coral.

"Then there are multiple groups looking at the bacterial communities associated with the corals, exploring whether you can inoculate them with bacteria that give them bleaching resilience. There is work going on in the UK on that. I think Saudi Arabia at KAUST University was the first group in the world to start actually inoculating corals in the wild with this, so it has gone past lab phases and is now happening in the ocean.”

Changing the genetics

Returning to the concept of the holobiont, he explains:

“The algae and the coral are just one part of it. The holobiont is really about looking at it as a mega organism where you've got all these interactions working together. If you throw one out of balance it has a knock-on effect, so it's incredibly complicated."

"Then there are groups looking at multi-generational work. It may be that you've created a super coral, but does that genetically get passed on to the offspring? One of my PhD supervisors is James Guest at Newcastle University. His group, Coralassist, is leading the way on that work, out in Palau.

"The work that is happening out there is just brilliant. We are seeing that yes: there is multi-generational impact, which gives a huge amount of hope that the selective breeding does get passed on, and that those traits are inherited.”

Beyond Project Coral: looking at the future of coral reefs

In terms of the future of the coral reefs and the oceans, he feels the narrative has changed:

“I've been going to coral reef conferences for 20 years now, and the energy in the rooms has changed hugely. It used to be incredibly depressing. You'd come out of a meeting feeling, ‘The whole lot's going to die - it's knackered.’"

"Now there is definitely more of a mood of, ‘Look, what can we do? Let's put our brains together to try and figure out what positivity we can bring to this.’

That change in mentality certainly gives me a lot of hope.”

Additionally:

“There is more money now involved at multiple levels to try and make a difference, which, again, is very interesting and exciting, since it means these big scalability ideas can be tested.”

A dire situation

Nevertheless, he stresses the gravity of the situation:

“There are no two ways about it: it’s still a dangerous situation. We are losing reefs at an incredibly fast rate that doesn't seem to be slowing down. While I'm optimistic that lots of people are now thinking and working on trying to find solutions, it doesn't take away the urgency. It needs to happen now.

"When you look at the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) reports, it does not look good at all: reefs, as we know them, will be fundamentally changed forever. That's sobering.

"Even at a 1.5-degree rise, we are looking at 90% of coral reefs being affected. At 2 degrees - and we are on a trajectory for a two-degree rise - that rises to something like 99.8%. The prognosis is definitely not good.”

Good aquariums play a key role

He addresses the function of an aquarium such as the Horniman ’s at this point in time:

“We have a huge number of visitors that will never get to a coral reef, or to the Amazonian rainforest. Many will only go down to the British coast a handful of times in their life.

"We think about our aquariums as windows to nature, so we are quite purist in that we want them to represent the wild habitat as closely as possible. We don't want to be mixing species from all around the world just to make a pretty collection; we're trying to show something that is as natural as possible."

"Our demographic at the Horniman is very young. We want to engage the imaginations of those future generations and instil not only a sense of respect for the natural world but the feeling that it is something they want to cherish and look after. Education is a massive part of that engagement, and so are wonder, and enjoyment. It should be enjoyable.

"The vast majority of children have a natural and innate connection with nature. As we grow up, many people lose that connection. We want people to stay connected with nature throughout their life. We want to remove that disconnect. You’ll only protect something that you are engaged with, and that you love, and that’s what we want to inspire.”

Top image: Acropora millepora spawning, credit Jamie Craggs, Horniman Museum

TM Lim and Adam Wales

TM Lim and Adam Wales

Toby Harris

Toby Harris Hijingo

Hijingo Flight Club, Washington D.C.

Flight Club, Washington D.C.

Flight Club Philadelphia

Flight Club Philadelphia Flight Club Philadelphia

Flight Club Philadelphia Bounce

Bounce Hijingo

Hijingo Bounce

Bounce

Fernando Eiroa

Fernando Eiroa

Nickelodeon Land at Parque de Atracciones de Madrid

Nickelodeon Land at Parque de Atracciones de Madrid Raging Waters

Raging Waters  Mirabilandia's iSpeed coaster

Mirabilandia's iSpeed coaster Parque de Atracciones de Madrid

Parque de Atracciones de Madrid Ferracci at the ribbon-cutting ceremony for Nickelodeon Land at Mirabilandia, with (left) Marie Marks, senior VP of global experiences for Paramount and (cutting the ribbon) Sabrina Mangina, GM at Mirabilandia

Ferracci at the ribbon-cutting ceremony for Nickelodeon Land at Mirabilandia, with (left) Marie Marks, senior VP of global experiences for Paramount and (cutting the ribbon) Sabrina Mangina, GM at Mirabilandia Tropical Islands OHANA hotel

Tropical Islands OHANA hotel Elephants at Blackpool Zoo

Elephants at Blackpool Zoo  Tusenfryd

Tusenfryd

Andrew Thomas, Jason Aldous and Rik Athorne

Andrew Thomas, Jason Aldous and Rik Athorne