By Lou Pizante, The Experientialists

Not so long ago, you went somewhere to disappear—to lose yourself, not prove yourself.

Museums curated mastery. Your role was a reverent observer. Theater invited you to witness narratives in the dark, alongside others, without demanding the spotlight. Theme parks didn’t center you; they surrounded you. You were dropped into a fully built world, not to star in the story, but to move through it. These were spaces of awe, alignment, and collective rhythm.

But somewhere between the first Instagram selfie station and the third immersive Van Gogh, the spotlight began to shift. Experiences started increasingly behaving like mirrors instead of windows.

Now, increasingly, the story is about you.

Mirror, mirror, on the wall—who’s the most immersed of all?

We’re living in the golden age of curated epiphanies and mood-responsive scenography—peak main character energy design, complete with lighting cues tailored to your attachment style. This is the era where experience design doesn’t just immerse you. It platforms you.

It stages your arc around identity projection, selfie validation, and the fleeting catharsis of being emotionally available under algorithmically lit wonder.

To be clear: this isn’t about narcissism in the clinical sense. No one’s ordering electroshock for your projection-mapped self-worth. It’s a design condition, not a diagnosis.

The experiences we are building—and the ones we chase—to an increasing extent reflect a world where being in the spotlight, special, and spiritually retweeted isn’t the echo. It’s the intention.

That’s neither inherently good nor bad. But it’s definitely changing how we design for awe, connection, and meaning.

The mirror is a feature, not a flaw

Let’s not confuse performance with shallowness.

In a culture where many people, especially historically excluded groups, have been rendered invisible, the ability to center oneself can be a radical act. Self-authorship is not inherently performative. It can also be empowering, playful, even reparative.

Experiences like Netflix’s Squid Game: The Trials, Disney’s Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance, and HBO’s Westworld: Live Without Limits don’t just offer Instagrammable sets—they offer emotional fantasy fulfillment.

To compete for survival under the gaze of a giant animatronic schoolgirl with a machine gun, stage a daring escape from a First Order star destroyer, or betray an android outlaw to a robot sheriff and still feel morally compromised is to claim temporary narrative gravity. You’re not watching the story unfold—you’re wearing it, bending it, becoming its reason for happening.

This desire isn’t new. What’s new is how completely experiential producers are designing for it.

Gaming got there first, but social media gave it followers

Video games first let us try on heroism, build avatars, and test identities against imagined worlds. Branching narrative, feedback loops, and player agency laid the groundwork for today's experience economy, where guests expect to do something, become someone, and shape the story around them.

I’m convinced that the future of immersive theatre will take more from video games and apply it to live action.

“Video games are the most immersive entertainment form because the audience member has so much agency, and has the ability to craft and control and do whatever they want inside these alternate worlds,” says Felix Barrett, the artistic director of Punchdrunk, on a recent Stagecraft podcast."

“I’m convinced that the future of immersive theatre will take more from video games and apply it to live action.”

But if gaming gave us the mechanics—agency, identity, feedback—social media turned them into cultural reflexes. The desire to be seen, stylized, and storied migrated from digital fantasy into spatial experience design. Increasingly, the same instincts that drive us to scroll, post, and perform online are shaping how we move through immersive environments.

And we didn’t just import behaviors—we brought the algorithm with us.

Algorithmic architecture

More and more, immersive experiences behave like physical extensions of the scroll. Not nearly every experience leans this way, but the cultural gravity is hard to ignore.

Much of today’s spatial storytelling runs on “feed” logic: fast, flattering, feedback-driven. Bold visuals, smooth rhythms, and intuitive layouts turn space into content—the kind of spatial language that begs to be documented, shared, and fed back into the loop. This is algorithmic architecture: emotionally loud, visually sharp, and satisfying whether you stay a while or swipe on.

The result? A genre of experience that rewards resonance over depth, identity projection over transformation, and interaction over introspection.

You don’t need to look far to see it in action. Just head to Area15, the Vegas strip’s physical manifestation of your For You Page.

In Meow Wolf ’s Omega Mart, the aisles are just the front: behind the faux-brand packaging and glitchy freezer doors lie portals, backrooms, and a collapsing corporate mythos. The story unfolds only if you dig—but the architecture rewards your curiosity, placing you at the center of a systems failure that always seems one surreal clue ahead of you.

The John Wick Experience drops you into a moody neonscape and hands you a mission—though let’s be honest, you’re mostly there to dodge assassins and look expensive in motion blur. Each scene is short, cinematic, and suspiciously well-lit—like a noir remake of that Instagram reel where you took a sunset walk from the airport hotel to Chili’s.

Then there’s Superplastic’s Dopeameme, where plot gives way to punchlines you only sort of understand, but your dopamine centers applaud anyway. Here, you’re not only the main character, you’re the meme. It’s sort of like wandering the collective unconscious of the internet after it microdosed on its own neural net residue.

Still, the algorithm only tells half the story. It shapes the space, but parasocial dynamics shape how we respond.

Parasocial playgrounds

As the line between audience and performer blurs, immersive experiences have become parasocial playgrounds. Places where you simulate intimacy without the risk of rejection. Where you get emotional payoff without vulnerability, applause without effort, and the starring role—without ever giving a supporting one.

Sandbox VR nails this. Sure, you fight aliens or zombies, but the real payoff is watching the trailer of yourself doing it. Your group’s cinematic action montage becomes the souvenir: not just a memory, but a story where you’re brave, bonded, heroic—edited and optimized before your adrenaline even drops.

LA’s cult-favorite haunted playdate, Delusion, pushes it further. It’s danger in dress-up, with emotional rubber knives. You’re whispered into the story, handed secret tasks, pulled into private scenes. It feels personal, pivotal, like fate. But nothing’s really at stake. Delusion sells the thrill of transformation without asking you to change—like a trust fall into a pile of monogrammed pillows.

And then there’s You Me Bum Bum Train, the apex of extreme POV immersion, where you’re catapulted into lives you’ve never rehearsed and roles you definitely didn’t audition for.

One minute you’re leading a boardroom, the next you’re delivering a baby on a moving train, and somehow, everyone’s applauding. It’s like being trapped in other people’s expectations, only they’re delighted, you’re confused, and nobody asks you to clean up afterward.

It’s the simulation of significance—spotlight, stakes, and standing ovations, minus the messy consequences. This is protagonism as a service: all climactic music, no second-act struggles.

And it’s deeply effective. But it also lays bare one of the biggest questions in experiential right now: are we crafting mirrors or catalysts?

Main character energy: experience as identity simulator

In The Experience Economy, Joe Pine and James Gilmore defined the holy grail of guest experience as “transformational”—the kind that changes how you think, feel, or act.

But that’s not what many main character energy experiences aim for. They don’t want to change you. They want to affirm the version of yourself you most want to believe in, or, at least, the one you’re currently A/B testing.

That’s not a failure of ambition. It’s a feature of the format. Identity simulation is now part of the product.

These experiences aren’t built to challenge your sense of self. They’re designed to make it feel emotionally legible, aesthetically intentional, and heroically centered. It’s not transformation. It’s a personality preview.

You can see it across mediums and genres:

At WaveXR concerts, your avatar climbs the social ladder by radiating unfiltered joy. Clap more, glow more, and you might just ascend to the front row in a stadium built entirely from serotonin and code. It’s not fandom—it’s feedback. A live-streamed affirmation engine disguised as a rave.

At Dubai’s Museum of the Future, AI-powered guides greet you by name, clock your mood, and adjust their tone accordingly—like if Clippy got a master's in emotional intelligence. It’s smooth, sleek, and just uncanny enough to feel intimate. But you’re not being seen. You’re being softly flattered, elegantly echoed. Not transformed. Framed.

Then there’s Darkfield’s Arcade. You sit alone in the dark, headphones on, facing a vintage game cabinet that seems to know your secrets. One coin, one button, and suddenly you’re the lead in a branching story that’s part noir, part nightmare. Your choices steer the tone—charming, chaotic, cruel. It’s not transformation—it’s choose-your-own-identity, rendered in binaurial dread.

This pattern is everywhere. And the cultural script? It plays out in the same familiar beats—feedback, personalization, aesthetic control—shaped by years of swiping and self-curating.

It’s not always intentional. But it’s rarely accidental. Main character energy experiences and social platforms are now evolving in the same cultural petri dish. Built by the same UX minds. Driven by the same dopamine economics. Optimized for the same user need: to feel seen, affirmed, and maybe even storied.

It’s not transformation. It’s self-curation, with lighting cues.

And in this algorithmic mirror, the story that matters most isn’t the one unfolding around you. It’s the one you get to believe about yourself—engineered for memory, moment, and meaning.

But if every guest is a protagonist now, the big question becomes: how do you build a story that lets them act like one? Increasingly, experience designers are trading fixed arcs for flexible frameworks—ones that can hold a mirror, and still hold meaning.

Narrative in the age of the mirror

Traditional storytelling asks you to surrender. Main character energy design asks: What if, instead, the spotlight followed you, and the story bent around your choices?

To meet this shift, designers embrace modular narratives—whether Aaron A. Reed ’s “Narrative Play” (which maps story to desire: control, authorship, immersion) or the industry’s folk taxonomy of divers, skimmers, and waders—all converging on one truth: meet guests where they are, but leave the depths unlocked.

It’s no accident that some of the most resonant experiences are designed with opt-in depth.

In JFI Productions’ The Willows, you might sip wine with an unsettling aunt or slip upstairs to uncover a ghost’s final wish. The story deepens if you pursue it, but never punishes you for skimming. It just leaves the mirror slightly fogged.

Bristol’s Wake the Tiger works the same way. Some guests surrender to the art itself, drifting through the subliminally skewed wonderland of Meridia, letting neon fractals and warped domestic surrealism wash over them, no story required. Others chase secret doors, cryptic messages, and cosmic threads that hint at a deeper narrative lurking just beyond the OUTERverse. Either way, the experience holds.

There’s always a surface to perform on but also a deeper track for guests who don’t just surrender to the art, but to the arc. This allows for scalable intimacy, where the spotlight is wide enough to hold you, but flexible enough to shift when you let go.

But is it shallow?

Only if we let it be.

There’s nothing wrong with giving guests a spotlight. The experiences featured here, for example, represent main character energy design at its most effective—technically accomplished, culturally attuned, and often exhilarating in their execution.

But not every mirror shows you something with seeing.

If every moment is designed only as a mirror, what happens to meaning? What happens to surprise, to shared emotion, to the kind of story that lasts longer than a scroll?

A world optimized solely for content but starved of connection will eventually run out of soul. Aesthetic without friction. Performance without intimacy. Main character energy without narrative gravity.

So, does that mean main character energy design has to be transformational to be effective?

Not exactly. This is where it helps to revisit The Experience Economy. Yes, Pine and Gilmore put “transformation” at the top of the experiential value ladder. But they never said every attraction should be an escape room designed by Carl Jung.

Experience strategist Laura Hess, creator of the REMARKABLE framework, and someone who’s clocked more immersive experiences than most of us have unread terms and conditions, calls out this core misunderstanding:

“I think the discussion of ‘transformation’ has lost some of its meaning. What was singular is now often regarded as a necessary element, a design requirement we can engineer on demand.”

That misread? It’s where a lot of creative pressure (and bad marketing copy) came from.

Not every experience needs to change your life. But the good ones should want to leave something behind.

“The goal of experience,” says Hess, “is not always to change someone. It can be to hold them. To meet them where they are. To help them feel more like themselves.”

So, no—main character energy design isn’t inherently shallow. But if we stop there, if we never invite the guest to look past their own reflection, we’ve missed the deeper play.

The goal isn’t to break the mirror. It’s to smuggle a little meaning through it.

Because the best experiences don’t always change you, but they do leave something behind. A flicker of self-awareness. A question you didn’t expect. A moment that made the spotlight feel earned—not just algorithmically granted.

Designing for narcissism… and then past it

The real opportunity is to design with main character energy in mind—then take guests somewhere they weren’t expecting to go. To begin with authorship and agency and end, not necessarily in transformation, but in that shimmering moment where the mirror winks back and says, “Yeah, that’s you.”

Designing for the main character energy deserves its own manifesto. But for now, here are a few provocations and future-forward moves:

Ritual and rhythm give experiences a heartbeat beyond the selfie. Othership choreographs sweat, silence, scent, and sound into something that’s part spa, part ceremony, part urban shamanism. You’re not just invited to relax—you’re asked to show up. To feel something. To sweat out what’s no longer you, with a roomful of strangers who somehow aren’t.

Use personalization smartly to anchor connection or reflection. At Coke’s 2024 “Spiced Shop,” guests described how the new Spiced flavor felt, and then AI spun that sensory language into surreal portraits. It was branding, sure, but the kind that paused to ask who you are before telling you what to consume.

Ensemble moments are where guests realize they’re part of a larger arc. In Third Rail’s celebrated Then She Fell, guests drifted through eerie, intimate scenes—sometimes solo, sometimes paired—each moment feeling personal. But just when you forget others exist, you were pulled into a shared ritual or quiet convergence, reframing your private path as part of something larger and meticulously choreographed.

And never forget surprise. The Drop by Swamp Motel hijacked your life for 72 hours via phone. It wasn’t a narrative—it was a conspiracy, where your agency was bait, your texts were suspect, and your only Instagram post was a cryptic plea for help.

If you do it right, the guest still gets their selfie. But they leave with something bigger: a story they didn’t expect to be part of, and maybe didn’t even recognize as theirs.

Until they looked up.

This article is part of an ongoing exploration of the evolving immersive landscape—how we lost our way, who’s fighting to bring meaning back, and why it matters.

For more on what this column is all about, start with Is This Article Immersive?, where I lay out the mission: reclaiming immersion from the gimmick merchants and giving it back to those who create experiences worth disappearing into.

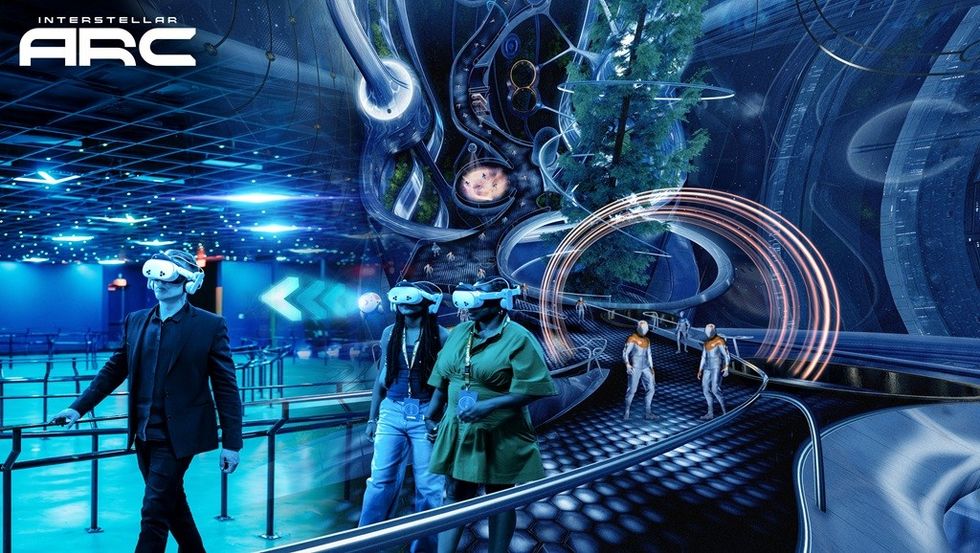

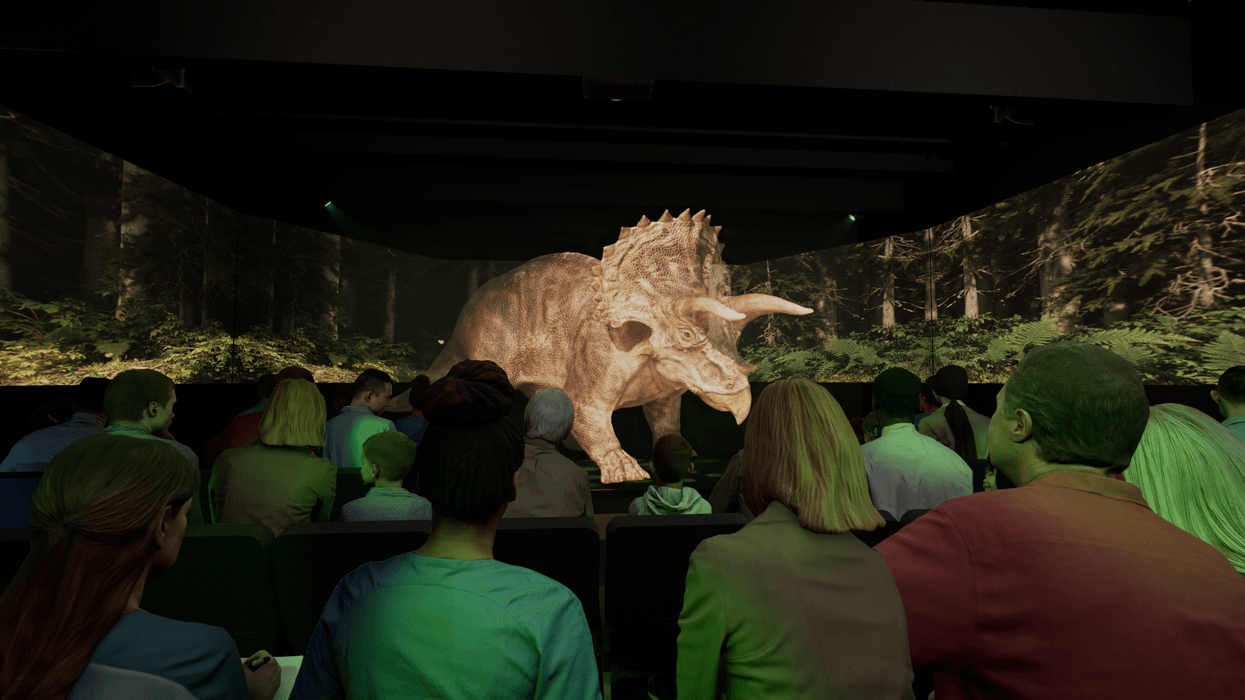

Images provided courtesy of High Note Events and Experiential Media Group

Images provided courtesy of High Note Events and Experiential Media Group Images provided courtesy of High Note Events and Experiential Media Group

Images provided courtesy of High Note Events and Experiential Media Group